Fuchs dystrophy

Fuchs' dystrophy; Fuchs' endothelial dystrophy; Fuchs' corneal dystrophy

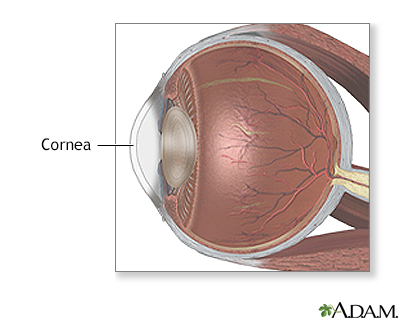

Fuchs (pronounced "fooks") dystrophy is an eye disease in which cells lining the inner surface of the cornea slowly start to die off. The disease most often affects both eyes.

Images

Causes

Fuchs dystrophy can be inherited, which means it can be passed down from parents to children. If either of your parents has the disease, you have a 50% chance of developing the condition.

However, the condition may also occur in people without a known family history of the disease.

Fuchs dystrophy is more common in women than in men. Vision problems do not appear before age 50 years in most cases. However, a health care provider may be able to see signs of the disease in affected people by their 30s or 40s.

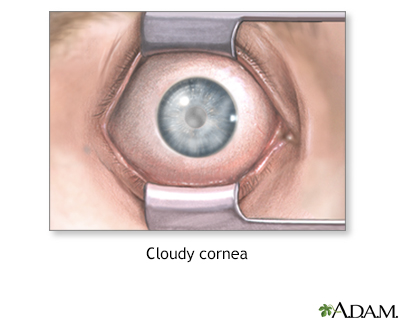

Fuchs dystrophy affects the thin layer of cells (endothelium) that lines the back part of the cornea. These cells help pump excess fluid out of the cornea. As more and more cells are lost, fluid begins to build up in the cornea, causing swelling and a cloudy cornea. Another reason for visual loss is the development of gutatta, which are little bumps that develop in the endothelium. These bumps can cause glare by breaking up the incoming light rays.

At first, fluid may build up only during sleep, when the eye is closed. As the disease gets worse, small blisters may form. The blisters get bigger and may eventually break. This causes eye pain. Fuchs dystrophy can also cause the shape of the cornea to change, leading to more vision problems.

Symptoms

Symptoms may include:

- Eye pain

- Eye sensitivity to light and glare

- Foggy or blurred vision, at first only in the mornings

- Seeing colored halos around lights

- Worsening vision throughout the day

Exams and Tests

An eye doctor can diagnose Fuchs dystrophy during a slit-lamp exam.

Other tests that may be done include:

- Pachymetry -- measures the thickness of the cornea

- Specular microscope examination -- allows the eye doctor to look at the thin layer of cells that line the back part of the cornea

- Visual acuity test

Treatment

Eye drops or ointments that draw fluid out of the cornea are used to relieve symptoms of Fuchs dystrophy.

If painful sores develop on the cornea, soft contact lenses or surgery to create flaps over the sores may help reduce pain.

The only cure for Fuchs dystrophy is a corneal transplant.

Until recently, the most common type of corneal transplant was penetrating keratoplasty. During this procedure, a small round piece of the cornea is removed, leaving an opening in the front of the eye. A matching piece of cornea from a human donor is then sewn into the opening in the front of the eye.

A newer technique called endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK, DSAEK, or DMEK) has become the preferred option for people with Fuchs dystrophy. In this procedure, only the inner layers of the cornea are replaced, instead of all the layers. This leads to a faster recovery and fewer complications. Stitches are most often not needed.

For people with Fuchs dystrophy that have mostly guttata and not much swelling, stripping off a small central disk of the endothelium containing the guttata can be helpful. In this method, DWEK, transplanting new endothelium, as would be done in DSEK, DSAEK or DMEK, is not necessary.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Fuchs dystrophy gets worse over time. Without a corneal transplant, a person with severe Fuchs dystrophy may become blind or have severe pain and very reduced vision.

Mild cases of Fuchs dystrophy often worsen after cataract surgery. A cataract surgeon will evaluate this risk and may modify the technique or the timing of your cataract surgery.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have:

- Eye pain

- Eye sensitivity to light

- The feeling that something is in your eye when there is nothing there

- Vision problems such as seeing halos or cloudy vision

- Worsening vision

Prevention

There is no known prevention. Avoiding cataract surgery or taking special precautions during cataract surgery may delay the need for a corneal transplant.

References

Altamirano F, Ortiz-Morales G, O'Connor-Cordova MA, Sancén-Herrera JP, Zavala J, Valdez-Garcia JE. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: an updated review. Int Ophthalmol. 2024;44(1):61. PMID: 38345780 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38345780/.

Castellucci M, Novara C, Casuccio A, et al. Bilateral ultrathin descemet's stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty vs. bilateral penetrating keratoplasty in Fuchs' dystrophy: corneal higher-order aberrations, contrast sensitivity and quality of life. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(2):133. PMID: 33546152 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33546152/.

Romano V, Passaro ML, Bachmann B, Baydoun L, Ni Dhubhghaill S, Dickman M, Levis HJ, Parekh M, Rodriguez-Calvo-De-Mora M, Costagliola C, Virgili G. Combined or sequential DMEK in cases of cataract and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2024 Feb;102(1):e22-30. PMID: 37155336 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37155336/.

Rosado-Adames N, Afshari NA. Diseases of the corneal endothelium. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 4.21.

Vieira R, Castro C, Coelho J, Mesquita Neves M, Gomes M, Oliveira L. Descemet stripping without endothelial keratoplasty in early-stage central fuchs endothelial dystrophy: long-term results. Cornea. 2023;42(8):980-985. PMID: 36731082 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36731082/.

BACK TO TOPReview Date: 8/5/2024

Reviewed By: Franklin W. Lusby, MD, Ophthalmologist, Lusby Vision Institute, La Jolla, CA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Health Content Provider

06/01/2025

|

A.D.A.M., Inc. is accredited by URAC, for Health Content Provider (www.urac.org). URAC's accreditation program is an independent audit to verify that A.D.A.M. follows rigorous standards of quality and accountability. A.D.A.M. is among the first to achieve this important distinction for online health information and services. Learn more about A.D.A.M.'s editorial policy, editorial process and privacy policy. A.D.A.M. is also a founding member of Hi-Ethics. This site complied with the HONcode standard for trustworthy health information from 1995 to 2022, after which HON (Health On the Net, a not-for-profit organization that promoted transparent and reliable health information online) was discontinued. |

The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. © 1997- 2025 A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.