Ammonia blood test

Serum ammonia; Encephalopathy - ammonia; Cirrhosis - ammonia; Liver failure - ammonia

The ammonia test measures the level of ammonia in a blood sample.

Images

I Would Like to Learn About:

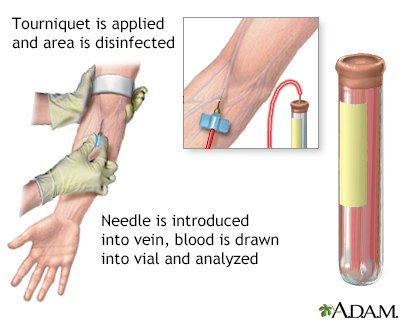

How the Test is Performed

A blood sample is needed.

How to Prepare for the Test

Your health care provider may ask you to stop taking certain drugs that may affect test results. These include:

- Alcohol

- Acetazolamide

- Barbiturates

- Diuretics

- Narcotics

- Valproic acid

You should not smoke before your blood is drawn.

How the Test will Feel

When the needle is inserted to draw blood, some people feel moderate pain. Others feel only a prick or stinging. Afterward, there may be some throbbing or a slight bruise. This soon goes away.

Why the Test is Performed

Ammonia (NH3) is produced by cells throughout the body, especially the intestines, liver, and kidneys. Most of the ammonia produced in the body is used by the liver to produce urea. Urea is also a waste product, but it is much less toxic than ammonia. Ammonia is especially toxic to the brain. It can cause confusion, low energy, and sometimes coma.

This test may be done if you have, or your provider thinks you have, a condition that may cause a toxic buildup of ammonia. It is most commonly used to diagnose and monitor hepatic encephalopathy, a severe liver disease.

Normal Results

The normal range is 15 to 45 µ/dL (11 to 32 µmol/L).

Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Some labs use different measurements or may test different samples. Talk to your provider about the meaning of your specific test results.

What Abnormal Results Mean

Abnormal results may mean you have increased ammonia levels in your blood. This may be due to any of the following:

- Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, usually in the upper GI tract

- Genetic diseases of the urea cycle

- High body temperature (hyperthermia)

- Kidney disease

- Liver failure

- Low blood potassium level (in people with liver disease)

- Parenteral nutrition (nutrition by vein)

- Reye syndrome

- Salicylate poisoning

- Severe muscle exertion

- Ureterosigmoidostomy (a procedure to reconstruct the urinary tract in certain illnesses)

- Urinary tract infection with a bacteria called Proteus mirabilis

A high-protein diet can also raise the blood ammonia level.

Risks

There is little risk in having your blood taken. Veins and arteries vary in size from one person to another and from one side of the body to the other. Taking blood from some people may be more difficult than from others.

Other risks associated with having blood drawn are slight, but may include:

- Excessive bleeding

- Fainting or feeling lightheaded

- Multiple punctures to locate veins

- Hematoma (blood accumulating under the skin)

- Infection (a slight risk any time the skin is broken)

Related Information

MetabolismHeart failure

Hemolytic disease of the newborn

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Pericarditis

Reye syndrome

References

Daniels L, Khalili M, Goldstein E, Bluth MH, Bowne WB, Pincus MR. Evaluation of liver function. In: McPherson RA, Pincus MR, eds. Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 24th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 22.

Mehta SS, Fallon MB. Hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and other systemic complications of liver disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 94.

BACK TO TOPReview Date: 2/28/2023

Reviewed By: Jacob Berman, MD, MPH, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Health Content Provider

06/01/2025

|

A.D.A.M., Inc. is accredited by URAC, for Health Content Provider (www.urac.org). URAC's accreditation program is an independent audit to verify that A.D.A.M. follows rigorous standards of quality and accountability. A.D.A.M. is among the first to achieve this important distinction for online health information and services. Learn more about A.D.A.M.'s editorial policy, editorial process and privacy policy. A.D.A.M. is also a founding member of Hi-Ethics. This site complied with the HONcode standard for trustworthy health information from 1995 to 2022, after which HON (Health On the Net, a not-for-profit organization that promoted transparent and reliable health information online) was discontinued. |

The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. © 1997- 2025 A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.