Changes in the newborn at birth

Birth - changes in the newborn

Changes in the newborn at birth refer to the changes an infant's body undergoes to adapt to life outside the womb.

Images

I Would Like to Learn About:

Information

LUNGS, HEART, AND BLOOD VESSELS

The mother's placenta helps the baby "breathe" while it is growing in the womb. Oxygen and carbon dioxide flow through the blood in the placenta. Most of it goes to the heart and flows through the baby's body. This allows for the baby to have the proper amount of these chemicals in their body.

At birth, the baby's lungs are filled with fluid. They are not inflated. The baby takes the first breath within about 10 seconds after delivery. This breath sounds like a gasp, as the newborn's central nervous system reacts to the sudden change in temperature and environment.

Once the baby takes the first breath, a number of changes occur in the infant's lungs and circulatory system:

- Increased oxygen in the lungs causes a decrease in blood flow resistance to the lungs.

- Blood flow resistance of the baby's blood vessels also increases.

- Fluid drains or is absorbed from the respiratory system.

- The lungs inflate and begin working on their own, moving oxygen into the baby's bloodstream and removing carbon dioxide by breathing out (exhalation).

BODY TEMPERATURE

A developing baby produces about twice as much heat as an adult. A small amount of heat is removed through the developing baby's skin, the amniotic fluid, and the uterine wall.

After delivery, the newborn begins to lose heat. Receptors on the baby's skin send messages to the brain that the baby's body is cold. The baby's body creates heat by burning stores of brown fat, a type of fat found only in fetuses and newborns. Newborns are rarely seen to shiver.

LIVER

In the baby, the liver acts as a storage site for sugar (in the form of a chemical called glycogen) and iron. When the baby is born, the liver has various functions:

- It produces substances that help the blood to clot.

- It begins breaking down waste products such as excess red blood cells.

- It produces a protein that helps break down bilirubin. If the baby's body does not properly break down bilirubin, it can lead to newborn jaundice.

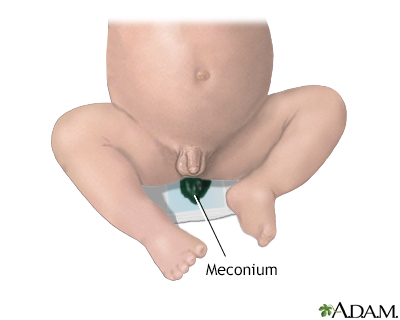

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

A baby's gastrointestinal system doesn't fully function until after birth.

In late pregnancy, the baby produces a tarry green or black waste substance called meconium. Meconium is the medical term for the newborn infant's first stools. Meconium is composed of amniotic fluid, mucus, lanugo (the fine hair that covers the baby's body before birth), bile, and cells that have been shed from the skin and intestinal tract. In some cases, the baby passes stools (meconium) while still inside the uterus.

URINARY SYSTEM

The developing baby's kidneys begin producing urine by 9 to 12 weeks into the pregnancy. After birth, the newborn will usually urinate within the first 24 hours of life. The kidneys become able to maintain the body's fluid and electrolyte balance.

The rate at which blood filters through the kidneys (glomerular filtration rate) increases sharply after birth and in the first 2 weeks of life. Still, it takes some time for the kidneys to get up to speed. Newborns have less ability to remove excess salt (sodium) or to concentrate or dilute the urine compared to adults. This ability improves over time.

IMMUNE SYSTEM

The immune system begins to develop in the baby, and continues to mature through the child's first few years of life. The womb is a relatively sterile environment. But as soon as the baby is born, they are exposed to a variety of bacteria and other potentially disease-causing substances. Although newborn infants are more vulnerable to infection, their immune system can respond to infectious organisms.

Newborns do carry some antibodies from their mother, which provide protection against infection. Breastfeeding also helps improve a newborn's immunity by continuing to supply antibodies from the mother to the baby.

SKIN

Newborn skin will vary depending on the length of the pregnancy. Premature infants have thin, transparent skin. The skin of a full-term infant is thicker.

Characteristics of newborn skin:

- A fine hair called lanugo might cover the newborn's skin, especially in preterm babies. The hair should disappear within the first few weeks of the baby's life.

- A thick, waxy substance called vernix may cover the skin. This substance protects the baby while floating in amniotic fluid in the womb. Vernix should wash off during the baby's first bath.

- The skin might be cracking, peeling, or blotchy, but this should improve over time.

References

Marcdante KJ, Kliegman RM, Schuh AM. Assessment of the mother, fetus, and newborn. In: Marcdante KJ, Kliegman RM, Schuh AM, eds. Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 58.

Olsson JM. The newborn. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 21.

Rozance PJ, Wright CJ. The neonate. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 23.

BACK TO TOPReview Date: 11/6/2023

Reviewed By: Neil K. Kaneshiro, MD, MHA, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Health Content Provider

06/01/2025

|

A.D.A.M., Inc. is accredited by URAC, for Health Content Provider (www.urac.org). URAC's accreditation program is an independent audit to verify that A.D.A.M. follows rigorous standards of quality and accountability. A.D.A.M. is among the first to achieve this important distinction for online health information and services. Learn more about A.D.A.M.'s editorial policy, editorial process and privacy policy. A.D.A.M. is also a founding member of Hi-Ethics. This site complied with the HONcode standard for trustworthy health information from 1995 to 2022, after which HON (Health On the Net, a not-for-profit organization that promoted transparent and reliable health information online) was discontinued. |

The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. © 1997- 2025 A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.