Urge incontinence

Overactive bladder; Detrusor instability; Detrusor hyperreflexia; Irritable bladder; Spasmodic bladder; Unstable bladder; Incontinence - urge; Bladder spasms; Urinary incontinence - urge

Urge incontinence occurs when you have a strong, sudden need to urinate that is difficult to delay. The bladder then squeezes, or spasms, and you may lose urine.

Images

Animation

Causes

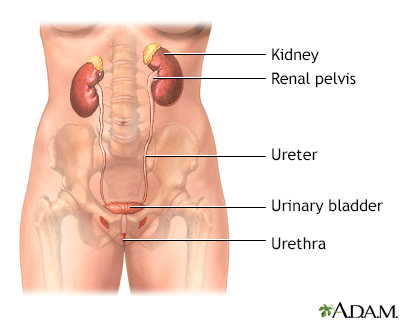

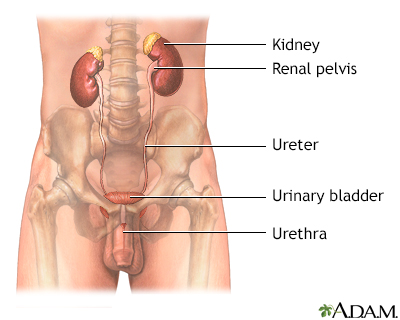

As your bladder fills with urine from the kidneys, it stretches to make room for the urine. You should feel the first urge to urinate when there is a bit less than 1 cup (240 milliliters) of urine in your bladder. Most people can hold more than 2 cups (480 milliliters) of urine in the bladder.

Two muscles help prevent the flow of urine:

- The sphincter is a muscle around the opening of the bladder. It squeezes to prevent urine from leaking into the urethra. This is the tube that urine passes through from your bladder to the outside.

- The bladder wall muscle relaxes so the bladder can expand and hold urine.

When you urinate, the bladder wall muscle squeezes to force urine out of the bladder. As this happens, the sphincter muscle relaxes to allow the urine to pass through.

All of these systems must work together to control urination:

- Your bladder muscles and other parts of your urinary tract

- The nerves controlling your urinary system

- Your ability to feel and respond to the urge to urinate

The bladder may contract too often due to nervous system problems or bladder irritation.

URGE INCONTINENCE

With urge incontinence, you leak urine because the bladder muscles squeeze, or contract, at the wrong times. These contractions often occur no matter how much urine is in the bladder.

Urge incontinence may result from:

- Bladder cancer

- Bladder inflammation

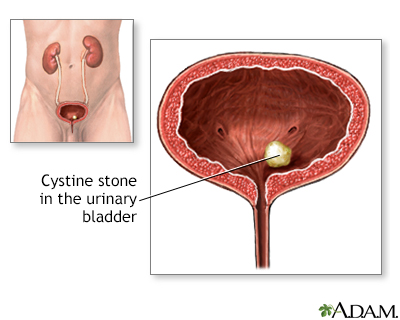

- Something blocking urine from leaving the bladder

- Bladder stones

- Infection

- Brain or nerve problems, such as multiple sclerosis or stroke, that affects the bladder muscles

- Nerve injury, such as from a spinal cord injury

In men, urge incontinence also may be due to:

- Bladder changes caused by an enlarged prostate, called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

- An enlarged prostate blocking urine from flowing from the bladder

In most cases of urge incontinence, no cause can be found.

Although urge incontinence may occur in anyone at any age, it is more common in women and older adults.

Symptoms

Symptoms include:

- Not being able to control when you pass urine

- Having to urinate often during the day and night

- Needing to urinate suddenly and urgently

Exams and Tests

During a physical exam, your health care provider will look at your belly and rectum.

- Women will have a pelvic exam.

- Men will have a genital exam.

In most cases, the physical exam will not find any problems. If there are nervous system causes, other problems also may be found.

Tests may include the following:

- Cystoscopy to view the inside of your bladder.

- Pad test. You wear a pad or pads to collect all of your leaked urine. Then the pad is weighed to find out how much urine you lost.

- Pelvic or abdominal ultrasound.

- Uroflow study to see how much and how fast you urinate.

- Post void residual to measure the amount of urine left in your bladder after you urinate.

- Urinalysis to check for blood in the urine.

- Urine culture to check for infection.

- Urinary stress test (you stand with a full bladder and cough).

- Urine cytology to check for bladder cancer.

- Urodynamic studies to measure bladder pressure and urine flow.

- X-rays with contrast dye to look at your kidneys and bladder.

- Voiding diary to assess your fluid intake, urine output, and urination frequency.

Treatment

Treatment depends on how bad your symptoms are and how they affect your life.

There are four main treatment approaches for urge incontinence:

- Bladder and pelvic floor muscle training

- Lifestyle changes

- Medicines

- Surgery

BLADDER RETRAINING

Managing urge incontinence most often begins with bladder retraining. This helps you become aware of when you lose urine because of bladder spasms. Then you relearn the skills you need to hold and release urine.

- You set a schedule of times when you should try to urinate. You try to avoid urination between these times.

- One method is to force yourself to wait 30 minutes between trips to the bathroom, even if you have an urge to urinate in between these times. This may not be possible in some cases.

- As you become better at waiting, gradually increase the time by 15 minutes until you are urinating every 3 to 4 hours.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING

Sometimes, Kegel exercises, biofeedback, or electrical stimulation may be used with bladder retraining. These methods help strengthen the muscles of your pelvic floor:

Kegel exercises -- These are mainly used to treat people with stress incontinence. However, these exercises may also help relieve the symptoms of urge incontinence.

- You squeeze your pelvic floor muscles like you are trying to stop the flow of urine.

- Do this for 3 to 5 seconds, and then relax for 5 seconds.

- Repeat 10 times, 3 times a day.

Vaginal cones -- This is a weighted cone that is inserted into the vagina to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles.

- You place the cone into the vagina.

- Then you try to squeeze your pelvic floor muscles to hold the cone in place.

- You can wear the cone for up to 15 minutes at a time, 2 times a day.

Biofeedback -- This method can help you learn to identify and control your pelvic floor muscles.

- Some therapists place a sensor in the vagina (for women) or the anus (for men) so they can tell when they are squeezing the pelvic floor muscles.

- A monitor will display a graph showing which muscles are squeezing and which are at rest.

- The therapist can help you find the right muscles for performing Kegel exercises.

Electrical stimulation -- This uses a gentle electrical current to contract your bladder muscles.

- The current is delivered using an anal or vaginal probe.

- This therapy may be done at the provider's office or at home.

- Treatment sessions usually last 20 minutes and may be done every 1 to 4 days.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) -- This treatment may help some people with overactive bladder.

- An acupuncture needle is placed behind the ankle, and electrical stimulation is used for 30 minutes.

- Most often, treatments will occur weekly for around 12 weeks, and perhaps monthly after that.

LIFESTYLE CHANGES

Pay attention to how much water you drink and when you drink.

- Drinking enough water will help keep odors away.

- Drink a little bit of fluid at a time throughout the day, so your bladder does not need to handle a large amount of urine at one time. Drink less than 8 ounces (240 milliliters) at one time.

- Do not drink large amounts of fluids with meals.

- Sip small amounts of fluids between meals.

- Stop drinking fluids about 2 hours before bedtime.

It also may help to stop consuming foods or drinks that may irritate the bladder, such as:

- Caffeine

- Highly acidic foods, such as citrus fruits and juices

- Spicy foods

- Artificial sweeteners

- Alcohol

Avoid activities that irritate the urethra and bladder. This includes taking bubble baths or using harsh soaps.

MEDICINES

Medicines used to treat urge incontinence relax bladder contractions and help improve bladder function. There are several types of medicines that may be used alone or together:

- Anticholinergic medicines help relax the muscles of the bladder. They include oxybutynin (Oxytrol, Ditropan), tolterodine (Detrol), darifenacin (Enablex), trospium (Sanctura), and solifenacin (VESIcare).

- Beta agonist medicines can also help relax the muscles of the bladder. The only medicine of this type currently is mirabegron (Myrbetriq).

- Flavoxate (Urispas) is a medicine that calms muscle spasms. However, studies have shown that it is not always effective at controlling symptoms of urge incontinence.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine) help relax the smooth muscle of the bladder.

- Botox injections are commonly used to treat overactive bladder. The medicine is injected into the bladder through a cystoscope. The procedure is most often done in the provider's office.

These medicines may have side effects such as dizziness, constipation, or dry mouth. Talk with your provider if you notice bothersome side effects.

If you have an infection, your provider will prescribe antibiotics. Be sure to take the entire amount as directed.

SURGERY

Surgery can help your bladder store more urine. It can also help relieve the pressure on your bladder. Surgery is used for people who do not respond to medicines or who have side effects associated with medicines.

Sacral nerve stimulation involves implanting a small unit under your skin. This unit sends small electrical pulses to the sacral nerve (one of the nerves that comes out at the base of your spine). The electrical pulses can be adjusted to help relieve your symptoms.

Augmentation cystoplasty is performed as a last resort for severe urge incontinence. In this surgery, a part of the bowel is added to the bladder. This increases the bladder size and allows it to store more urine.

Possible complications include:

- Blood clots

- Bowel blockage

- Infection

- Slightly increased risk of tumors

- Not being able to empty your bladder -- you may need to learn how to put a catheter into the bladder to drain urine

- Urinary tract infection

Urinary incontinence is a long-term (chronic) problem. While treatments can cure your condition, you should still see your provider to make sure you are doing well and check for possible problems.

Outlook (Prognosis)

How well you do depends on your symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Many people must try different treatments (some at the same time) to reduce symptoms.

Getting better takes time, so try to be patient. A small number of people need surgery to control their symptoms.

Possible Complications

Physical complications are rare. The condition may get in the way of social activities, careers, and relationships. It can also make you feel bad about yourself.

Rarely, this condition can cause severe increases in bladder pressure, which can lead to kidney damage.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if:

- Your symptoms are causing problems for you.

- You have pelvic discomfort or burning with urination.

Prevention

Starting bladder retraining techniques early may help relieve your symptoms.

Related Information

Stress urinary incontinenceUrinary incontinence

Enlarged prostate

Urinary incontinence - injectable implant

Urinary incontinence - retropubic suspension

Urinary incontinence - urethral sling procedures

Urinary incontinence - tension-free vaginal tape

Urinary incontinence - what to ask your doctor

Urinary catheters - what to ask your doctor

Sterile technique

Urinary incontinence surgery - female - discharge

When you have urinary incontinence

Indwelling catheter care

Kegel exercises - self-care

Urine drainage bags

Self catheterization - female

Urinary incontinence products - self-care

References

Lentz GM, Miller JL. Lower urinary tract function and disorders: physiology of micturition, voiding dysfunction, urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections, and painful bladder syndrome. In: Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, Lobo RA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 21.

Lightner DJ, Gomelsky A, Souter L, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline Amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202(3):558-563. PMID: 31039103 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31039103/.

Newman DK, Burgio KL. Conservative management of urinary incontinence: behavioral and pelvic floor therapy and urethral and pelvic devices. In: Partin AW, Domochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 121.

Resnick NM, DuBeau CE. Urinary incontinence. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 115.

Reynolds WS, Cohn JA. Overactive bladder. In: Partin AW, Domochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 117.

Stiles M, Walsh K. Care of the elderly patient. In: Rakel RE, Rakel DP, eds. Textbook of Family Medicine. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 4.

BACK TO TOPReview Date: 7/1/2023

Reviewed By: Kelly L. Stratton, MD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Health Content Provider

06/01/2025

|

A.D.A.M., Inc. is accredited by URAC, for Health Content Provider (www.urac.org). URAC's accreditation program is an independent audit to verify that A.D.A.M. follows rigorous standards of quality and accountability. A.D.A.M. is among the first to achieve this important distinction for online health information and services. Learn more about A.D.A.M.'s editorial policy, editorial process and privacy policy. A.D.A.M. is also a founding member of Hi-Ethics. This site complied with the HONcode standard for trustworthy health information from 1995 to 2022, after which HON (Health On the Net, a not-for-profit organization that promoted transparent and reliable health information online) was discontinued. |

The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. © 1997- 2025 A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.