Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis

Periodic paralysis - thyrotoxic; Hyperthyroidism - periodic paralysis

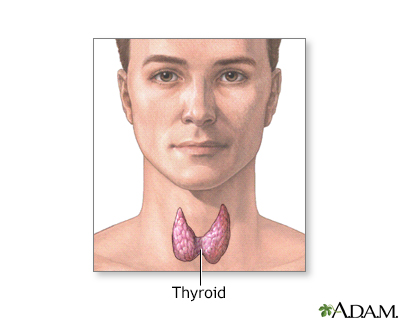

Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis (TPP) is a condition with episodes of severe muscle weakness. It occurs in people who have high levels of thyroid hormone in their blood. Examples of this include hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis.

Images

I Would Like to Learn About:

Causes

This rare condition occurs only in people with high (usually very high) thyroid hormone levels (thyrotoxicosis). Men of Asian or Hispanic descent are affected more often. Most people who develop high thyroid hormone levels are not at risk of periodic paralysis.

Hypokalemic, or familial, periodic paralysis is a similar disorder. It is an inherited condition and not related to high thyroid levels, but has the same symptoms.

Risk factors include a family history of periodic paralysis and hyperthyroidism.

Symptoms

Symptoms involve attacks of muscle weakness or paralysis. Between attacks, normal muscle function returns. Attacks often begin after symptoms of hyperthyroidism have developed. Hyperthyroid symptoms may be subtle.

The attacks may occur daily to yearly. Episodes of muscle weakness or paralysis may:

- Come and go

- Last from a few hours up to several days (rare)

- Occur more often in the legs than the arms

- Be most common in the shoulders and hips

- Be triggered by heavy, high-carbohydrate, high-salt meals

- Be triggered during rest after exercise

Other rare symptoms may include any of the following:

- Trouble breathing

- Speech problems

- Trouble swallowing

- Vision changes

During attacks, you will be alert and can answer questions. Normal strength returns between attacks. With repeated attacks, you may develop muscle weakness.

Symptoms of hyperthyroidism include:

- Excessive sweating

- Fast heart rate

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Heat intolerance

- Increased appetite

- Insomnia

- Having bowel movements more often

- Feeling strong heartbeat (palpitations)

- Tremors of the hand

- Warm, moist skin

- Weight loss

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider may suspect TPP based on:

- Abnormal thyroid hormone levels

- A family history of the disorder

- Low blood potassium level during attacks

- Symptoms that come and go

Diagnosis involves ruling out disorders caused by low blood potassium.

Your provider may try to trigger an attack by giving you insulin and sugar. The sugar is glucose, which reduces your potassium level. Or you may be given thyroid hormone.

The following signs may be seen during the attack:

- Decreased or no reflexes

- Abnormal heartbeat (arrhythmia)

- Low potassium in the blood (potassium levels are normal between attacks)

Between attacks, the examination is normal. Or, there may be signs of hyperthyroidism. These include an enlarged thyroid, changes in the eyes, tremors, or hair and nail changes.

The following tests are used to diagnose hyperthyroidism:

- High thyroid hormone levels (T3 or T4)

- Low serum TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) levels

- Thyroid uptake and scan

Other test results:

- Abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG) during attacks

- Abnormal electromyogram (EMG) during attacks

- Low serum potassium during attacks, but normal between attacks

A muscle biopsy may sometimes be taken.

Treatment

Potassium should be given during the attack, most often by mouth. If weakness is severe, you may need to get potassium through a vein (IV).

Note: You should only get IV potassium if your kidney function is normal and you are monitored in the hospital.

Weakness that involves the muscles used for breathing or swallowing is an emergency. People must be taken to a hospital. Serious irregularity of the heartbeat also occurs during attacks.

Your provider may recommend a diet low in carbohydrates and salt to prevent attacks. You may be given beta-blocker medicines to reduce the number and severity of attacks while your hyperthyroidism is brought under control.

Acetazolamide is effective at preventing attacks in people with familial periodic paralysis. It is usually not effective for TPP.

Outlook (Prognosis)

If an attack isn't treated and the breathing muscles are affected, death can occur.

Chronic attacks over time can lead to muscle weakness. This weakness can continue even between attacks if the thyrotoxicosis is not treated.

TPP responds well to treatment. Treating hyperthyroidism will prevent attacks. It may even reverse muscle weakness.

Possible Complications

Untreated TPP can lead to:

- Difficulty breathing, speaking, or swallowing during attacks (rare)

- Heart arrhythmias during attacks

- Muscle weakness that gets worse over time

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call 911 or the local emergency number or go to the emergency room if you have periods of muscle weakness. This is especially important if you have a family history of periodic paralysis or thyroid disorders.

Emergency symptoms include:

- Difficulty breathing, speaking, or swallowing

- Falls due to muscle weakness

Prevention

Genetic counseling may be advised. Treating the thyroid disorder prevents attacks of weakness.

Related Information

WeaknessHyperthyroidism

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis

Muscle function loss

Muscle cramps

Potassium test

Arrhythmias

Carbohydrates

Breathing difficulty

References

Hollenberg A, Wiersinga WM. Hyperthyroid disorders. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig RJ, Rosen CJ, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 12.

Kang MK, Kerchner GA, Ptacek LJ. Channelopathies: Episodic and electrical disorders of the nervous system. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 98.

Selcen D. Muscle diseases. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 389.

Weetman AP, Kahaly GJ. Graves disease. In: Robertson RP, ed. DeGroot's Endocrinology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 71.

BACK TO TOPReview Date: 2/28/2024

Reviewed By: Sandeep K. Dhaliwal, MD, board-certified in Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism, Springfield, VA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Health Content Provider

06/01/2025

|

A.D.A.M., Inc. is accredited by URAC, for Health Content Provider (www.urac.org). URAC's accreditation program is an independent audit to verify that A.D.A.M. follows rigorous standards of quality and accountability. A.D.A.M. is among the first to achieve this important distinction for online health information and services. Learn more about A.D.A.M.'s editorial policy, editorial process and privacy policy. A.D.A.M. is also a founding member of Hi-Ethics. This site complied with the HONcode standard for trustworthy health information from 1995 to 2022, after which HON (Health On the Net, a not-for-profit organization that promoted transparent and reliable health information online) was discontinued. |

The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. © 1997- 2025 A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.