SmartEngageTM

Diabetes - type 1 - InDepth

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of type 1 diabetes.

I Would Like to Learn About:

- Frequent urination

- Excessive thirst

- Extreme hunger

- Sudden weight loss

- Extreme fatigue

- Irritability

- Blurred vision

- Sweating

- Trembling

- Hunger

- Rapid heartbeat

- Confusion

- Headache

- Weakness

- During and immediately after a meal, digestion breaks carbohydrates down into sugar molecules (of which glucose is one), and proteins into amino acids.

- Right after the meal, glucose and amino acids are absorbed directly into the bloodstream, and blood glucose levels rise sharply. (Glucose levels after a meal are called post-prandial levels.)

- The rise in blood glucose levels signals important cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, to secrete insulin, which pours into the bloodstream. Within 20 minutes after a meal insulin rises to its peak level.

- Insulin enables glucose to enter cells in the body, particularly muscle and fat cells. Insulin is also important in telling the liver how to process glucose. Insulin and other hormones direct whether glucose will be burned for energy or stored for future use.

- When insulin levels are high, the liver stops producing glucose and stores it in other forms until the body needs it again.

- As blood glucose levels start to come down after a meal, the pancreas reduces the production of insulin.

- About 2 to 4 hours after a meal both blood glucose and insulin are back at low levels. The blood glucose levels are then referred to as pre-prandial blood glucose concentrations.

- The rapid or gradual destruction of beta cells in the pancreas. Eventually, the pancreas can no longer produce insulin.

- Without insulin to move glucose into cells, blood glucose levels become excessively high, a condition known as hyperglycemia.

- Because the body cannot utilize the sugar, it spills over into the urine and causes more frequent urination, dehydration, and thirst.

- Weakness, weight loss, frequent urination, and excessive hunger and thirst are among the initial symptoms.

- People with type 1 diabetes need to take daily insulin for survival.

- Being ill in early infancy

- Having a parent with type 1 diabetes (the risk is greater if the father has the condition)

- Having a mother who is older at the time of pregnancy

- Having a mother who had preeclampsia during pregnancy

- Having other autoimmune disorders such as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis (a form of hypothyroidism), Addison disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), or pernicious anemia

- Frequent urination (in children, a recurrence of bed-wetting after toilet training has been completed)

- Unusual thirst, particularly for sweet, cold drinks

- Extreme hunger

- Sudden, sometimes dramatic, weight loss

- Weakness

- Extreme fatigue

- Blurred vision or other changes in eyesight

- Irritability

- Nausea and vomiting

- Good control of blood glucose and keeping glycated hemoglobin (A1C) levels below or around 7%. This approach can help prevent complications due to vascular (blood vessel) abnormalities and nerve damage (neuropathy) that can cause major damage to organs, including the eyes, kidneys, and heart and can result in blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks, strokes, foot ulcers, infection of bones in the feet, and toe or foot amputation.

- Managing risk factors for heart disease. Blood glucose control helps the heart. But it is also very important that people with diabetes control blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and other factors associated with heart disease, including stopping use of all tobacco products.

- Thirst and dry mouth

- Frequent urination

- Fatigue

- Dry warm skin

- Nausea and vomiting

- Stomach pain

- Deep and rapid breathing, sometimes with frequent sighing

- Fruity breath odor

- Confusion and decreased consciousness

- Attempting too-tight control of blood glucose and A1c levels

- Long-term diabetes, even more likely when kidney problems are present

- Not complying with treatment (taking insulin some days, but not on other days)

- Infections such as gastroenteritis or respiratory illnesses

- Taking rapid-acting insulin to correct high blood glucose without eating

- Liver disease

- Substance abuse, including alcohol use

- Sweating

- Trembling

- Hunger

- Rapid heartbeat

- Headache

- Confusion

- Weakness

- Disorientation

- Combativeness

- In rare and worst cases, coma, seizure, and death

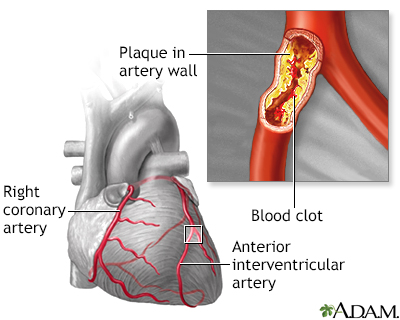

- Both type 1 and 2 diabetes accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). Diabetes is often associated with low HDL ("good" cholesterol) and high triglycerides. This can lead to coronary artery disease, heart attack, or stroke.

- In type 1 diabetes, high blood pressure (hypertension) usually develops if the kidneys become damaged. High blood pressure is another major cause of heart attack, stroke, and heart failure. Children with diabetes are also at risk for hypertension.

- Impaired nerve function (neuropathy) associated with diabetes also causes heart abnormalities.

- Sensory. Affects nerves in the toes, feet, legs, hand, and arms.

- Autonomic. Affects nerves that help regulate digestive, bowel, bladder, heart, and sexual function. Autonomic dysfunction also affects sweat glands and can cause very sweaty or dry feet.

- There are also motor (muscle) and joint neuropathy that can affect the feet.

- Tingling

- Weakness

- Burning sensations

- Loss of the sense of warm or cold

- Numbness (if the nerves are severely damaged, the person may be unaware that a blister or minor wound has become infected)

- Deep pain

- Extremely dry feet, which can lead to fungal and other skin infections.

- Digestive problems (such as constipation, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting).

- Bladder infections and incontinence.

- Erectile dysfunction.

- Heart problems. Neuropathy may mask angina, the warning chest pain for heart disease and heart attack. People with diabetes should be aware of other warning signs of a heart attack, including sudden fatigue, sweating, shortness of breath, nausea, and vomiting.

- Rapid heart rates.

- Lightheadedness when standing up (orthostatic hypotension).

- The early and more common type of this disorder is called nonproliferative or background retinopathy. The blood vessels in the retina are abnormally weakened. They rupture and leak, and waxy areas may form in the retina. If these processes affect the central portion of the retina, swelling may occur, causing reduced or blurred vision.

- If the capillaries become blocked and blood flow is cut off, soft, "woolly" areas may develop in the retina's nerve layer. These woolly areas may signal the development of proliferative retinopathy. In this more severe condition, new abnormal blood vessels form and grow on the surface of the retina. They may spread into the cavity of the eye or bleed into the back of the eye. Major hemorrhage or retinal detachment can result, causing severe visual loss or blindness. The sensation of seeing flashing lights may indicate retinal detachment.

- Hearing loss.

- Periodontal disease.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome and other nerve entrapment syndromes.

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, also called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH); a particular danger for people who are obese. This is now one of the leading causes of cirrhosis (a failing liver) and liver transplantation.

- Very aggressive, rapidly progressive infections below the skin. They often occur in the groin area (called Fournier's gangrene), but can also be on the legs or abdominal wall.

- Fasting plasma glucose (FPG)

- Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

- Normal. Below 100 mg/dL.

- Prediabetes (a risk factor for type 2 diabetes). Between 100 and 125 mg/dL.

- Diabetes. 126 mg/dL or higher.

- It first uses an FPG test.

- A blood test is then taken 2 hours later after drinking a special glucose solution.

- Normal. Below 140 mg/dL.

- Prediabetes. Between 140 and 199 mg/dL.

- Diabetes. 200 mg/dL or higher.

- Normal. Below 5.7%.

- Pre-Diabetes. Between 5.7% and 6.4%.

- Diabetes. 6.5% or higher.

- Every 6 months if diabetes is well controlled

- Every 3 months if not well controlled

- Choose carbohydrates that come from vegetables, whole grains, fruits, beans (legumes), and dairy products. Avoid carbohydrates that contain added fats, sugar, or sodium.

- Choose "good" fats over "bad" ones. The type of fat may be more important than the quantity. Monounsaturated (olive, peanut, and canola oils; avocados; and nuts) and omega-3 polyunsaturated (fish, flaxseed oil, and walnuts) fats are the best types of fats. Avoid unhealthy saturated fats (red meat, butter) and trans fats (hydrogenated fat found in snack foods, fried foods, commercially baked goods).

- Choose protein sources that are low in saturated fat. Fish, poultry, legumes, and soy are better protein choices than red meat. Try to eat fatty fish (salmon, tuna), which are high in omega-3 fatty acids, at least twice a week.

- Eliminate or limit intake of sugar-sweetened beverages including those that contain high fructose corn syrup or sucrose. They are bad for your waistline and your heart.

- Sodium (salt) intake should be limited to 2,300 mg/day or less. People with diabetes and high blood pressure may need to restrict sodium even further. Reducing sodium can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of heart disease and heart failure.

- Monitor glucose levels carefully before, during, and after workouts.

- Avoid exercise if glucose levels are above 300 mg/dL or under 100 mg/dL.

- To avoid hypoglycemia, people should inject insulin in sites away from the muscles they use the most during exercise.

- Before exercising, avoid alcohol and if possible certain drugs, including beta blockers, which make it difficult to recognize symptoms of hypoglycemia.

- Insulin-dependent athletes may need to decrease insulin doses or take in more carbohydrates, in the form of pre-exercise snacks. Skim milk is particularly helpful. They should also drink plenty of fluids.

- Good, protective footwear is essential to help avoid injuries and wounds to the feet.

- There is a greater risk for low blood sugar (hypoglycemia).

- Many people experience significant weight gain from insulin administration, which may have adverse effects on blood pressure and cholesterol levels. It is important to manage heart disease risk factors that might develop as a result of insulin treatment.

- Goal for adult is 80 to 130 mg/dL.

- Goal for children is about 90 to 130 mg/dL up to 180 mg/dL for children experiencing low blood sugar levels.

- Less than 180 mg/dL for adults.

- 120 to 180 mg/dL for most children.

- 90 to 150 to 180 mg/dL for most children, but an ideal goal for each individual child should be set, and may depend on history of hypoglycemia, awareness of hypoglycemia, lifestyle, and other problems.

- Basal insulin administration. The basal component of the treatment attempts to provide a steady amount of background insulin throughout the day to prevent excess production and release of glucose by the liver. Basal insulin levels maintain regular blood glucose needs. Several long-acting insulins, including insulin glargine offers consistent insulin activity level when given once a day. For some people with type 1 diabetes glargine does not last the full 24 hours. Other intermediate and long-acting forms may be beneficial when administered twice a day. Short-acting insulin delivered continuously using a pump is another way to provide basal rates of insulin.

- Meal-time insulin administration. Meals require a boost (a bolus) of insulin to regulate the sudden rise in glucose levels after a meal. This insulin is designed to prevent an increase in blood sugar resulting from a meal or a snack.

- Perform 4 or more blood glucose tests during the day (point of care, fingerstick, using a glucose meter). This needs to be done even if you have a continuous glucose monitor.

- Coordinate insulin administration with calorie intake. In general, eat 3 meals each day at regular intervals. Snacks may be necessary, but can also mean that basal insulin rates are too high and may contribute to weight gain.

- Insulin requirements vary depending on many non-nutritional situations during the day, including exercise, stress, and sleep. Exercise increases the risk for low blood sugar. Some people experience a sudden rise in blood glucose levels in the morning -- the so-called "dawn phenomenon." This also happens if the blood sugars are too low during sleep at 3 a.m. to 4 a.m. which can trigger an excessive hormonal response.

- It is important to maintain a good diet plan and visit your health care team (doctor, nurse, and dietitian) as often as once a month.

- The duration of insulin action. Insulin is available in several forms, including: regular, intermediate, long-acting, and rapid-acting.

- Amount and type of food eaten. Ingestion of food makes the blood glucose level rise. Alcohol reduces the ability of the liver to prevent hypoglycemia.

- A person's level of physical activity. Exercise lowers glucose levels.

- Diuretics rid the body of extra sodium (salt) and water. There are three main types of diuretics: Potassium-sparing, thiazide (can increase blood sugar levels), and loop.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors reduce the production of angiotensin, a chemical that causes arteries to narrow.

- Angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) block angiotensin.

- Beta blockers block the effects of adrenaline and ease the heart's pumping action.

- Calcium-channel blockers (CCBs) decrease the contractions of the heart and widen blood vessels. Like ACE inhibitors and ARBs, certain calcium channel blockers (diltiazem and verapamil) can reduce urine protein loss caused by diabetic kidneys.

- Reducing intake of saturated fats, trans fats, and dietary cholesterol

- Increasing intake of omega-3 fatty acids, viscous fiber, and plant stanols

- Weight loss if necessary

- Increased physical activity

- Antibiotics are generally given. In some cases, hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics for up to 28 days may be needed for severe foot ulcers and for people who have peripheral artery disease.

- In virtually all cases, wound care requires debridement, which is the removal of injured tissue until only healthy tissue remains. Debridement may be accomplished using chemical (enzymes), surgical, or mechanical (irrigation) means.

- Hydrogels (such as NU-GEL) may help soothe and heal ulcers.

- Felted foam may be helpful in healing ulcers on the sole of the foot. Felted foam uses a multi-layered foam pad over the bottom of the foot with an opening over the ulcer.

- Administering hyperbaric oxygen (oxygen given at high pressure) is generally reserved for people with severe, full thickness diabetic foot ulcers that have not responded to other treatments, particularly when gangrene or an abscess is present. It is not recommended for infection in the bone (osteomyelitis). Its usefulness or benefit is not well proven or accepted.

- Total contact casting (TCC) uses a cast that is designed to match the exact contour of the foot and distribute weight along the entire length of the foot. It is usually changed weekly. It may be helpful for ulcer healing and for Charcot foot. Although it is very effective in healing ulcers, recurrence is common.

- Other devices such as cast walkers and shoe modifications that offload the weight and pressure over an area may be used.

- Anticonvulsants. Pregabalin (Lyrica) is a first-line treatment and has the strongest evidence for efficacy of all neuropathy treatments. Gabapentin (Neurontin, generic) and valproate (Depacon, generic) may also be considered.

- Antidepressants. Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor) are recommended, as is amitriptyline (Elavil, generic). Venlafaxine may be given in combination with gabapentin. Duloxetine and venlafaxine are serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant. Tricyclics may cause heart rhythm problems, so people at risk need to be monitored carefully.

- Opioids. Opioids are powerful prescription narcotic painkillers. Morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol (Ultram, generic) may be considered for severe neuropathy pain. These drugs can cause significant side effects (nausea, constipation, and headache) are highly addictive, so benefits should be weighed against these risks, the treatment closely monitored, and decisions made together with the person.

- Topical Medications. Capsaicin ointment or a lidocaine skin patch may be effective. These treatments are applied directly to the skin. Capsaicin is the active ingredient in hot chili peppers.

- For people with diabetes who have microalbuminuria, the American Diabetes Association strongly recommends ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Microalbuminuria is an accumulation of protein in the urine, which can signal the onset of kidney disease (nephropathy).

- Nearly all people who have diabetes and high blood pressure should take an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) as part of their regimen for treating their hypertension. Such people will need to have their potassium checked regularly, as potassium levels can rise with these medications.

- Maintain hemoglobin levels between 10 to 12 g/dL.

- Receive frequent blood tests to monitor hemoglobin levels.

- Contact their doctors if they experience such symptoms as shortness of breath, pain, swelling in the legs, or increases in blood pressure.

- Intensive blood sugar control during pregnancy can reduce the risk of health complications for both mothers and babies. Doctors recommend that pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes monitor their blood sugar levels up to 8 times daily. This includes checking your blood glucose before each meal, 1 to 2 hours after a meal, at bedtime, and possibly during the night.

- Insulin needs increase during the pregnancy, during the last 3 months. Your doctor may recommend increasing your insulin dosage during this time.

- Your provider may ask you to do blood tests to measure plasma anhydro-D-glucitol, a good marker of blood glucose control in pregnancy.

- Consult a registered dietician to help adjust your food plan during pregnancy.

- Low-impact aerobic exercise during pregnancy can lower glucose levels. (All pregnant women, particularly those with diabetes, should check with their doctors before embarking on a rigorous exercise regimen. This is important for women with eye, kidney, or high blood pressure or other heart problems.)

- To prevent birth defects that affect the heart and nervous system, women with diabetes should take a higher dose of folic acid from the time of conception up to week 12 of pregnancy. They should also be checked for any heart problems.

- Women with diabetes should have an eye examination during pregnancy and up to a year afterward.

- Before meals and snacks

- Occasionally after eating

- At bedtime

- Before and after exercise

- When performing critical activities such as driving

- When low blood sugar is suspected (test again after treating hypoglycemia)

- More frequent monitoring may be needed during times of illness or stress

- Pre-meal glucose levels of 70 to 130 mg/dL

- Post-meal glucose levels of less than 180 mg/dL

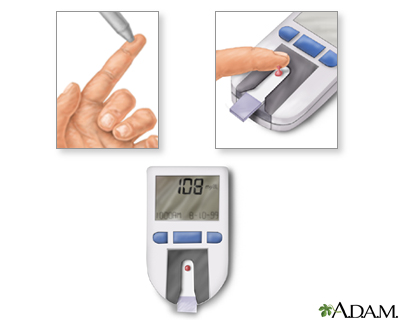

- A drop of blood is obtained by pricking the warm, clean, dry finger with a designated lancet.

- The blood is then applied to a chemically treated test strip that is inserted correctly in the glucose meter.

- The meter displays the glucose result.

- Using fresh strips; outdated strips may not provide accurate results. Always close the bottle tightly. Avoid exposure of the strips to heat and cold. Be sure the strips you are using match the meter.

- Keeping the meter clean.

- Periodically comparing the meter results with the results from a laboratory.

- Have a bedtime snack if you have low blood sugar at night. Snacks that contain protein and healthy fats may be best. Discuss reducing the dose of basal insulin with your doctor.

- Children (particularly thin children) may be at higher risk for hypoglycemia because the insulin injection goes into muscle tissue. Pinching the skin so that only fat (and not muscle) tissue is gathered or using shorter needles may help.

- Monitor blood glucose levels as often as possible, generally 4 times or more per day. This is particularly important for people with hypoglycemia unawareness. Continuous glucose monitors can also be useful in these cases.

- Adults should be sure to monitor blood glucose levels before driving, when hypoglycemia can be very hazardous.

- People who are at risk for hypoglycemia should always carry hard candy, juice, sugar packets, or commercially available glucose tablets.

- People at high risk for severe hypoglycemia, and their family members, should consider having on hand a glucagon emergency kit. The kit is available by prescription and contains an injection of glucagon, a hormone that helps to quickly raise blood glucose levels in a person who cannot eat. Glucagon is now also available as a nasal powder.

- If the person is helpless but able to swallow (not unconscious), family or friends should administer 3 to 5 pieces of glucose tablets or hard candy, 2 to 3 packets of sugar, half a cup (4 ounces) of fruit juice, or a commercially available glucose solution.

- If there is inadequate response within 15 minutes, the person should receive additional sugar by mouth and may need emergency medical treatment, possibly including an intravenous glucose solution.

- Family members and friends can learn to inject glucagon (see above).

- Inspect your feet daily and watch for changes in color or texture, odor, and firm or hardened areas. These changes may indicate infection and potential ulcers. Ulcers can occur beneath areas of a callus.

- When washing the feet, the water should be warm (not hot) and the feet and areas between the toes should be thoroughly dried afterward. Check water temperature with the hand or a thermometer before stepping in.

- Apply moisturizers, but not between the toes.

- Gently use pumice to remove corns and calluses. Do not use medicated pads or try to shave the corns or calluses yourself.

- Trim toenails short and file the edges to avoid cutting adjacent toes.

- Well-fitting footwear is very important. Make sure your shoe is wide enough. Avoid high heels, sandals, flip-flops, and going barefoot. Shoes with a rocker sole may be particularly helpful because they reduce pressure under the heel and in the front of the foot. Custom-molded boots increase the surface area over which foot pressure is distributed. This reduces stress on ulcers and allows them to heal.

- Change shoes often during the day.

- Wear socks, particularly with extra padding (which can be specially purchased).

- Avoid tight stockings or any clothing that constricts the legs and feet.

- Consult a specialist in foot care for any problems.

- Pancreas transplant alone.

- Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant, in which the person receives a pancreas and kidney from the same deceased donor.

- Pancreas after kidney transplant, in which a kidney transplant is first performed, and a pancreas transplant is performed at a later time. The organs come from different deceased donors.

- American Diabetes Association -- www.diabetes.org

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases -- www.niddk.nih.gov

- JDRF (global organization funding type 1 diabetes research) -- www.jdrf.org

- National Eye Institute (NEI) -- www.nei.nih.gov

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics -- www.eatright.org

- National Kidney Foundation -- www.kidney.org

- Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet -- www.trialnet.org

- MedicAlert Foundation -- www.medicalert.org

- Children with Diabetes (online community) -- www.childrenwithdiabetes.com

- Endocrine Society -- www.endocrine.org

Highlights

Type 1 Diabetes

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce insulin. Insulin is a hormone that is involved in regulating blood sugar (glucose) by controlling how much glucose you make between meals and how you use and store glucose that you absorb after a meal.

People with type 1 diabetes usually need to take insulin multiple times a day, or continuously from a pump, and must carefully monitor their blood glucose levels to avoid serious complications.

Type 1 diabetes can occur at any age. But it is most commonly diagnosed in childhood or adolescence.

Symptoms of Diabetes

Symptoms of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes include:

In general, the symptoms of type 1 diabetes come on more abruptly and are more severe than those of type 2 diabetes. Not every person who develops diabetes has the same combination of symptoms.

Warning Signs of Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) occurs when blood sugar (glucose) levels fall below normal. All people with diabetes should be aware of these symptoms of hypoglycemia:

It is important to quickly treat hypoglycemia and raise blood sugar levels by drinking or eating sugar, sucking on hard candy, drinking fruit juice, or injecting the hormone glucagon. People who are at risk for hypoglycemia should carry some sugar product, or an emergency glucagon injection kit, in case hypoglycemia occurs. People should also wear a medical alert ID bracelet or necklace that states they have diabetes and take insulin.

Closed Loop Devices

Technology is moving forward in combining a device that adjusts the dose of insulin (and sometimes a dose of a second hormone called glucagon) in response to continuous glucose monitoring.

Introduction

The two major forms of diabetes are type 1 (previously called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), or juvenile-onset diabetes) and type 2 (previously called non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), or adult-onset diabetes).

In type 1 diabetes, the body does not make any insulin or produces only a small amount of insulin.

Insulin

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes share one central feature: elevated blood sugar (glucose) levels due to not having enough of a signal from insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. In type 1 diabetes the reason the insulin signal is insufficient is because the amount of insulin in the blood is too low. Insulin is a key regulator of the body's metabolism.

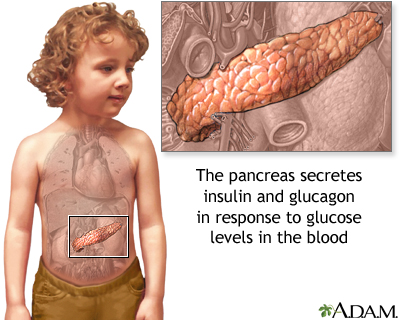

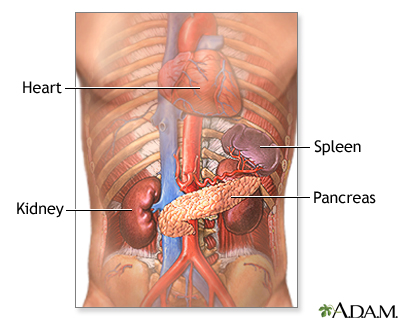

The pancreas is located below and behind the stomach. In addition to secreting digestive enzymes, the pancreas secretes the hormones insulin and glucagon into the bloodstream. The release of insulin into the blood lowers the level of blood glucose (simple sugars from food) by enhancing the ability of glucose to enter the body cells, where it is metabolized. If blood glucose levels get too low, the pancreas secretes glucagon to stimulate the release of glucose from the liver.

Types of Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1 Diabetes

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce insulin. Onset is usually in childhood or adolescence. But it can occur at any age and accounts for about 5% of people with diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is considered an autoimmune disorder that involves:

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, accounting for 90% of people with diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, the body does not respond properly to insulin which means the insulin signal is too low, a condition known as insulin resistance. Over time, the pancreas also becomes unable to produce insulin in adequate amounts to keep blood sugar normal.

Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes is a form of type 2 diabetes, usually temporary, that appears during pregnancy. It usually develops during the third trimester of pregnancy. After delivery, blood sugar (glucose) levels generally return to normal, although the risk of developing type 2 diabetes is higher and some women go on to develop type 2 diabetes.

Women who have type 1 or type 2 diabetes before their pregnancies do not have gestational diabetes.

Causes

Autoimmune Response

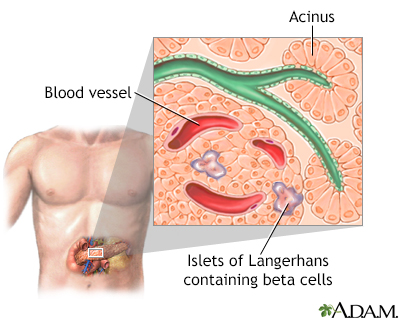

Type 1 diabetes is considered a progressive autoimmune disease, in which the beta cells that produce insulin are slowly destroyed by the body's own immune system. It is unknown what first starts this process. Evidence suggests that both a genetic predisposition and environmental triggering factors, such as a viral infection, are involved.

Islets of Langerhans contain beta cells and are located within the pancreas. Beta cells produce insulin which is needed to metabolize glucose within the body.

Genetic Factors

Researchers have identified at least 18 genetic locations, labeled IDDM1 - IDDM18, which are related to type 1 diabetes. The IDDM1 region contains the HLA genes that encode proteins called major histocompatibility complex. The genes in this region affect the immune response. Other chromosomes and genes that affect the risk of developing diabetes continue to be identified.

Most people who develop type 1 diabetes do not have a family history of the disease. The odds of inheriting the disease are only 10% if a first-degree relative has diabetes. Even in identical twins, one twin has only a 33% chance of having type 1 diabetes if the other twin has it. Children are more likely to inherit the disease from a father with type 1 diabetes than from a mother with the disorder.

Genetic factors cannot fully explain the development of diabetes. For the past several decades, the number of new cases of type 1 diabetes has been increasing each year worldwide.

Viruses

Some research suggests that viral infections may trigger the disease in genetically susceptible individuals.

Among the viruses under scrutiny are enteric viruses, which attack the intestinal tract. Coxsackieviruses are a family of enteric viruses of particular interest. Epidemics of Coxsackievirus, as well as mumps and congenital rubella, have been associated with type 1 diabetes.

Other Factors

Some researchers support the "hygiene hypothesis", which is the idea that the lack of early childhood exposure to infectious agents (through things like sanitation, wide use of antibiotics, cesarean delivery) makes the body's immune system more susceptible to respond excessively to regular or harmless stimuli. This hypothesis is partly supported by epidemiological data and applies to several allergic and autoimmune disorders including asthma and type 1 diabetes.

Besides enteric viral infections, other factors are also being studied as triggers for type 1 diabetes, including rubella, dietary factors, rapid growth, and psychological stress.

Risk Factors

Type 1 diabetes is much less common than type 2 diabetes, consisting of only about 5% to 10% of all cases of diabetes. Nevertheless, like type 2 diabetes, new cases of type 1 diabetes have been rising over the past few decades. While type 2 diabetes has been increasing among African-American and Hispanic adolescents, the highest rates of type 1 diabetes are found among Caucasian youth.

Type 1 diabetes can occur at any age but usually appears between infancy and the late 30s, most typically in childhood or adolescence. Males and females are equally at risk. Studies report the following may be risk factors for developing type 1 diabetes:

Symptoms

The process that destroys the insulin-producing beta cells can be long and invisible. However, at the point when insulin production becomes too low, type 1 diabetes usually appears suddenly and progresses quickly. Warning signs of type 1 diabetes include:

Children with type 1 diabetes may also be restless, apathetic, and have trouble functioning at school. In severe cases, diabetic coma may be the first sign of type 1 diabetes.

Complications

Diabetes increases the risk for many serious health complications. The good news is that during the past several decades, the rate of serious complications among people with diabetes has been decreasing, and more people are living longer and healthier lives.

There are 2 important approaches to preventing complications from type 1 diabetes.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a life-threatening complication caused by a complete (or almost complete) lack of insulin. In DKA, the body produces abnormally high levels of blood acids called ketones. Ketones are by-products of fat breakdown that build up in the blood and appear in the urine. They are produced when the body starts burning much larger amounts of fat than usual. The buildup of ketones in the body is called ketoacidosis. Extreme stages of DKA can lead to coma and death.

For some people, DKA may be the first sign that someone has type 1 diabetes. In type 1 diabetes, it usually occurs when a person is not taking insulin as prescribed, runs out of insulin, or cannot afford to buy medication. Sometimes people intentionally reduce insulin doses in order to lose weight. DKA can also be triggered by a severe illness or infection that weakens the immune system and stresses the body. Malfunction of an insulin pump can also allow DKA to develop.

Symptoms and complications of DKA include:

Cerebral edema, or brain swelling, is a rare but very dangerous complication that can result in coma, brain damage, or death. This is most common in children with DKA. Other serious complications from DKA include aspiration pneumonia, acute kidney injury, and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Life-saving treatment uses rapid replacement of fluids with a salt (saline) solution followed by insulin and potassium replacement.

Ketoacidosis is a serious condition of glucose build-up in the blood and urine. A simple urine test can determine if high ketone levels are present.

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Syndrome (HHS)

Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) is a serious complication of diabetes that involves a cycle of increasing blood sugar levels and dehydration, usually without increasing blood ketones. HHS usually occurs in people with type 2 diabetes. But it can also occur with type 1 diabetes. It is often triggered by a serious infection or another severe illness, or by medications that lower glucose tolerance or increase fluid loss (particularly in people who are not drinking enough fluids).

Symptoms of HHS include high blood sugar levels, dry mouth, extreme thirst, dry skin, and high fever. HHS can lead to loss of consciousness, seizures, coma, and death.

Hypoglycemia

Tight blood sugar (glucose) control increases the risk of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). Hypoglycemia occurs if blood glucose levels fall below normal. It is generally defined as a blood sugar below 70 mg/dL, although this level may not necessarily cause symptoms in all people.

Insufficient intake of food and excess exercise or alcohol intake may cause hypoglycemia. Usually the condition is manageable. Hypoglycemia can sometimes be severe or even life threatening, particularly if the person fails to recognize the symptoms, while continuing to take insulin or other hypoglycemic drugs. Beta-blocking medications, which are often prescribed for high blood pressure and heart disease, can mask symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Risk Factors for Severe Hypoglycemia

Specific risk factors for severe hypoglycemia include:

Hypoglycemia unawareness

Hypoglycemia unawareness is a condition in which people become accustomed to hypoglycemic symptoms. They may no longer have any signs of hypoglycemia until the hypoglycemia becomes severe. It affects about 25% of people who use insulin, nearly always people with type 1 diabetes. In such cases, hypoglycemia appears suddenly, without warning, and can escalate to a severe level.

Previous hypoglycemia is the biggest risk factor for hypoglycemic unawareness. Even a single recent episode of hypoglycemia may make it more difficult to detect the next episode. With vigilant monitoring and by rigorously avoiding low blood glucose levels, people can often regain the ability to sense hypoglycemia symptoms. However, sometimes continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is necessary to identify time periods when people are hypoglycemic. CGM studies have shown that many people with type 1 diabetes are sometimes unaware that their blood sugars are very low.

Symptoms of Hypoglycemia

Mild symptoms usually occur at moderately low and easily correctable levels of blood glucose. Not all people have the same symptoms. Many people with diabetes come to recognize their hypoglycemia symptom pattern over time and it is usually consistent. Early symptoms can include:

Severely low blood glucose levels can cause neurologic symptoms, such as:

[For information on preventing hypoglycemia or managing an attack, see the Home Management section of this report.]

Heart Disease and Stroke

People with diabetes are more likely than people who do not have diabetes to die from cardiovascular complications, including heart attack and stroke. Diabetes affects the heart in many ways:

Atherosclerosis is a disease of the arteries in which fatty material is deposited in the vessel wall, resulting in narrowing and eventual impairment of blood flow. Severely restricted blood flow in the arteries to the heart muscle leads to symptoms such as chest pain (often with activity). Atherosclerosis shows no symptoms until a complication occurs.

Click the icon to see an image of kidney anatomy.

Kidney Damage (Nephropathy)

Kidney disease (nephropathy) is a very serious complication of diabetes. With this condition, the tiny filters in the kidney (called glomeruli) become damaged and leak protein into the urine. Over time this can lead to kidney failure. Urine tests showing microalbuminuria (small amounts of protein in the urine) are important markers for kidney damage.

Diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). People with ESRD have 13 times the risk of death compared to other people with type 1 diabetes. If the kidneys fail, dialysis or transplantation is required. Symptoms of kidney failure may include swelling in the feet and ankles, itching, fatigue, and pale skin color. The outlook of ESRD has greatly improved during the last four decades for people with type 1 diabetes, and fewer people with type 1 diabetes are developing ESRD.

Neuropathy

Diabetes reduces or distorts nerve function, causing a condition called neuropathy. Neuropathy refers to a group of disorders that affect nerves. The two main types of neuropathy are:

Sensory neuropathy particularly affects the feet and legs. It is a common complication for people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The most serious consequences of neuropathy occur in the legs and feet and pose a risk for skin ulcers and infections in the bone and, in severe cases, amputation. Peripheral neuropathy usually starts in the toes and moves up the legs, and can also affect the fingers, hands, and arms (called a stocking-glove distribution). Symptoms can include:

Autonomic neuropathy can cause:

Diabetic gastroparesis is a type of neuropathy that affects the digestive tract. It is triggered by high blood sugar, which over time can damage the vagus nerve. The result of this damage is that the digestive system takes too long to move and digest food. Undigested food and the delay in stomach emptying can cause blood glucose levels to rise unpredictably, and make diabetes more difficult to control. Symptoms of gastroparesis include heartburn, nausea, abdominal bloating, feeling full after eating only a small amount of food, and vomiting of undigested food several hours after a meal. Gastroparesis generally only occurs in people who already have severe peripheral neuropathy. People with poorly-controlled blood sugars often have symptoms of gastroparesis, but this is reversible over weeks to months if blood glucose control improves.

Blood sugar control is an essential component in the treatment for neuropathy. Studies show that tight control of blood glucose levels delays the onset and slows progression of neuropathy. Heart disease risk factors may increase the likelihood of developing neuropathy. Lowering triglycerides, losing weight, reducing blood pressure, and quitting smoking may help prevent the onset of neuropathy.

Foot Ulcers and Amputations

About 15% of people with diabetes have serious foot problems. They are the leading cause of hospitalizations for these people. The consequences of both poor circulation and peripheral neuropathy make this a common and serious problem for all people with diabetes. Diabetes is responsible for more than half of all lower limb amputations performed in the US. Most amputations start with foot ulcers.

People with diabetes who are overweight, smokers, and have a long history of diabetes tend to be at most risk. People who have the disease for more than 20 years and are taking insulin are at the highest risk. Related conditions that put people at risk include peripheral neuropathy, peripheral artery disease (PAD), foot deformities, and a history of ulcers.

Foot ulcers usually develop from minor injury that goes unnoticed because of neuropathy. Infections can sometimes make the ulcer worse and can involve muscle and bone. About one-third of foot ulcers occur on the big toe. People with diabetes and neuropathy should check their feet every night before going to bed to look for redness, blisters, or ulcers. Calluses in areas where the feet experience the most pressure do not protect against foot ulcers.

Charcot Foot

Charcot foot or Charcot joint (medically referred to as neuropathic arthropathy) is a degenerative condition that affects the bones and joints in the feet. It is associated with the nerve damage that occurs with neuropathy. Early changes appear similar to an infection, with the foot becoming swollen, red, and warm and can be caused by twisting the foot or ankle while walking or stepping off a stair. Gradually, the affected foot can become deformed. The joints may shift, change shape, and become unstable and bones can fracture over time.

Charcot foot typically develops in people who have neuropathy to the extent that they cannot feel sensation in the foot and are not aware of an existing injury. Instead of resting an injured foot or seeking medical help, the person often continues normal activity, causing further damage.

Retinopathy and Eye Complications

Diabetes accounts for thousands of new cases of blindness annually and is the leading cause of new cases of blindness in adults ages 20 to 74 years. The most common eye disorder in diabetes is retinopathy. People with diabetes are also at higher risk for developing cataracts and certain types of glaucoma.

Retinopathy is a condition in which the retina becomes damaged. It generally occurs in one or two phases:

Click the icon to see an image of diabetic retinopathy.

Infections

Respiratory Infections

People with diabetes face a higher risk for influenza and its complications, including pneumonia. Everyone with diabetes should have annual influenza vaccinations and a vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia.

People with diabetes are at higher risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Risk of needing to be in the hospital and dying from COVID-19 is about three times higher than for people without diabetes. The biggest increase in risk due to diabetes is for patients with higher blood sugar levels (A1C above 10%).

Urinary Tract Infections

Women with diabetes face a significantly higher risk for urinary tract infections, which are likely to be more complicated and difficult to treat than in the general population.

Hepatitis

People with diabetes are at increased risk for contracting the hepatitis B virus, which is transmitted through blood and other bodily fluids. Exposure to the virus can occur through sharing finger-stick devices, blood glucose monitors, or insulin pens. Adults newly diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes should get hepatitis B vaccinations.

Depression

Diabetes doubles the risk for depression. Depression, in turn, may increase the risk for hyperglycemia and complications of diabetes.

Osteoporosis

Type 1 diabetes is associated with slightly reduced bone density, putting people at risk for osteoporosis and possibly fractures.

Other Complications

Diabetes increases the risk for other conditions, including:

Specific Complications in Women

Diabetes can cause specific complications in women. Women with diabetes have an increased risk of recurrent yeast infections. In terms of sexual health, diabetes may cause decreased vaginal lubrication, which can lead to pain or discomfort during intercourse.

Women with diabetes should be aware that certain types of medication can affect their blood glucose levels. For example, birth control pills can raise blood glucose levels. Long-term use (more than 2 years) of birth control pills may increase the risk of certain health problems.

Diabetes and Pregnancy

Diabetes during pregnancy can increase the risk for birth defects. High blood sugar levels (hyperglycemia) can affect the developing fetus during the critical first 6 weeks of organ development. Women with diabetes (either type 1 or type 2) who are planning on becoming pregnant should strive to maintain good glucose control for 3 to 6 months before pregnancy.

It is also important for women to closely monitor their blood sugar levels during pregnancy. For women with type 1 diabetes, pregnancy can affect their insulin dosing needs. Insulin dosing may also need to be adjusted during and following delivery. [For more information, see "Treatment of Diabetes During Pregnancy" in the Treatment of Complications section of this report.]

Diabetes and Menopause

The changes in estrogen and other hormonal levels that occur during the transition to menopause (perimenopause) can cause major fluctuations in blood glucose levels. Women with diabetes also face an increased risk of premature menopause, which can lead to higher risk of heart disease.

Specific Problems for Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes

Lack of Blood Glucose Control

Control of blood glucose levels is generally very poor in adolescents and young adults. Adolescents with diabetes are at higher risk than adults for ketoacidosis resulting from non-adherence with insulin management. Young people who do not control glucose are also at high risk for permanent damage in small blood vessels, such as those in the eyes. Many of these problems are made worse by the transition from pediatric care to adult medicine care. Many institutions have specific adolescent diabetes clinics to help to address this issue.

Eating Disorders

Up to a third of young women with type 1 diabetes have eating disorders and underuse insulin to lose weight. Anorexia and bulimia pose significant health risks in any young person. But they can be particularly dangerous for people with diabetes.

Diagnosis

There are 3 tests that can diagnose diabetes:

Fasting Plasma Glucose Test

The FPG test is the standard test for diagnosing diabetes. It is a simple blood test taken after 8 hours of fasting.

FPG levels indicate:

The FPG test is not always reliable, so a repeat test is recommended if the initial test suggests the presence of diabetes, or if the tests are normal in people who have symptoms or risk factors for diabetes. Widespread screening of people to identify those at higher risk for diabetes type 1 is not recommended. A point-of-care blood glucose test (fingerstick) does not suffice for diagnosing diabetes based on the FPG.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

The OGTT is more complex than the FPG and may over-diagnose diabetes in people who do not have it. Some doctors recommend it as a follow-up after FPG, if the latter test results are normal but the person has symptoms or risk factors of diabetes. The test uses the following procedures:

OGTT glucose levels at 2 hours indicate:

People who have the FPG and OGTT tests must not eat for at least 8 hours prior to the test.

Any random blood glucose of 200 mg/dL or higher, even without fasting, is also diagnostic of diabetes.

The OGTT is used to diagnose diabetes. The first portion of the test involves drinking a special glucose solution. Blood is then taken several hours later to test for the level of glucose in the blood. People with diabetes will have higher than normal levels of glucose in their blood.

Hemoglobin A1c Test

This test examines blood levels of glycated hemoglobin, also known as HbA1c. The results are given in percentages and broadly reflect a person's average blood glucose levels over the past 2 to 3 months. (The FPG and OGTT show a person's glucose level only at the time of the test.) The A1c test is not affected by recent food intake so people do not need to fast to prepare for it.

In addition to providing information on blood sugar control and effectiveness of diabetes treatment, the A1c test may also be used as an alternative test for diagnosing diabetes.

A1c levels indicate:

A1c tests are also used to help people with diabetes monitor how well they are keeping their blood glucose levels under control. For people with diabetes, A1c is measured periodically up to every 2 to 3 months, or at least twice a year. While finger prick self-testing provides information on blood glucose for that moment, the A1c test shows how well blood sugar has been controlled overall for the past several months.

Certain conditions that affect hemoglobin molecules or the lifespan of red blood cells (such as sickle cell disease, hemodialysis, or others) may influence A1C results. In these cases, plasma glucose tests may be used instead.

In general, most adult people with diabetes should aim for A1c levels below or around 7%. Your doctor may adjust this goal depending on your individual health profile. An A1c target of under 7.5% is recommended for older healthy adults. Older adults with other health problems may need higher target levels of 8.0% to 8.5%.

Goal A1c levels for all children (under 18 years) are less than 7.5%. The American Diabetes Association no longer recommends various age based A1c targets for children.

Schedule for A1c Monitoring:

The American Diabetes Association recommends that results from the A1c test be used to calculate estimated average glucose (eAG). EAG is a term that people may see on lab results from their A1c tests. It converts the A1c percentages into the same mg/dL units that people are familiar with from their daily home blood glucose tests. For example, an A1c of 7% suggests that the eAG is anywhere from 123 to 184 mg/dL with the most common average BG being 154 mg/dL.

The eAG terminology can help people better interpret the results of their A1c tests, and make it easier to correlate A1c with results from home blood glucose monitoring.

Autoantibody Tests

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by the presence of a variety of antibodies that react against the islet cells. These antibodies are referred to as autoantibodies because they recognize the body's own cells, rather than a foreign invader. Blood tests for these autoantibodies can help differentiate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. However, many people with type 2 diabetes also have low levels of one or more autoantibodies and so autoantibodies may simply be the sign of damaged pancreatic islets beta cells. New tests for autoantibodies are being developed as research in this area continues.

Screening Tests for Complications

Screening Tests for Heart Disease

All people with diabetes should be tested for high blood pressure (hypertension) and unhealthy cholesterol and lipid levels and given an electrocardiogram. Other tests may be needed in people with signs of heart disease.

Click the icon to see an image of an ECG.

Screening Tests for Kidney Damage

The earliest manifestation of kidney disease is microalbuminuria, in which tiny amounts of a key protein called albumin are found in the urine. Microalbuminuria is also a marker for other complications involving blood vessel abnormalities, including heart attack and stroke.

The American Diabetes Association recommends that people with diabetes receive an annual urine test for albumin. People should also have their blood creatinine tested at least once a year. Creatinine is a waste product that is removed from the blood by the kidneys. High levels of creatinine may indicate kidney damage. A doctor uses the results from a creatinine blood test to calculate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The GFR is an indicator of kidney function; it estimates how well the kidneys are cleaning the blood.

Screening for Retinopathy

The American Diabetes Association recommends that people with type 1 diabetes have an annual comprehensive eye exam, with dilation, to check for signs of retina disease (retinopathy). People at low risk may need exams only every 2 to 3 years. Instead of a comprehensive eye exam, digital retinal photography may be used as a screening tool. Retinal photography uses a special type of camera to take images of the back of the eye.

Screening for Neuropathy

All people should be screened for nerve damage (neuropathy), including an annual comprehensive foot exam. People who lose sensation in their feet should have a foot exam every 3 to 6 months to check for ulcers or infections. People should also be screened for intermittent claudication and PAD using the ankle-brachial index for diagnosis.

Lifestyle Changes

Good nutrition and regular physical activity can help prevent or manage medical complications of diabetes (such as heart disease and stroke), and help people live longer and healthier lives. Nutrition and activity in many ways are the cornerstones of blood glucose control.

Diet

There is no single best diabetes diet. People should meet with a professional dietitian to plan an individualized diet within the general guidelines that takes into consideration their own health needs. Diabetes self-management education programs can also provide valuable nutritional advice.

The American Diabetes Association no longer advises a uniform ideal percentage of daily calories for carbohydrates, fats, or protein for all people with diabetes. Rather, these amounts should be individualized, based on your unique health profile. Carbohydrate counting is important for people with type 1 diabetes. They need to match their insulin doses to carbohydrate intake.

Healthy eating habits along with good control of blood glucose are the basic goals, and several good dietary methods are available to meet them. Recommended eating plans include Mediterranean, vegetarian, and lower-carbohydrate diets. What is most important is to find a healthy eating plan that works best for you and your lifestyle and food preferences. Whatever eating plan you follow, try to eat a variety of nutrient-rich food in appropriate portion sizes.

The American Diabetes Association's most recent nutritional guidelines recommend:

Healthy Weight Control

Weight gain is a potential side effect of intense diabetic control with insulin. Being overweight can increase the risk for health problems. The amount of weight gain caused by insulin is variable. Insulin is a growth factor and contributes to increases in weight of fat and muscle. On the other hand, studies suggest that more than one-third of women with diabetes omit or underuse insulin in order to lose weight. Eating disorders are particularly dangerous in people with diabetes and can increase the risk for DKA. Ketoacidosis is a significant complication of insulin depletion and can be life threatening.

Exercise and Physical Activity

Aerobic activity has significant and particular benefits for people with type 1 diabetes. It increases sensitivity to insulin, lowers blood pressure, improves cholesterol levels, and decreases body fat. Because glucose levels can swing dramatically during workouts, people with type 1 diabetes need to take certain precautions:

Avoid resistance or high impact exercises. They can strain weakened blood vessels in the eyes of people with retinopathy. High-impact exercise may also injure blood vessels in the feet. Because people with diabetes may have silent heart disease, they should always check with their health care providers before undertaking vigorous exercise.

Warning on Dietary Supplements

Various fraudulent products are often sold on the Internet as "cures" or treatments for diabetes. These dietary supplements have not been studied or approved. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) warn people with diabetes not to be duped by bogus and unproven remedies.

According to the American Diabetes Association, there is no evidence to support herbal remedies or dietary supplements (including fish oil supplements) for the treatment of diabetes. There is no evidence that vitamin or mineral supplements can help people with diabetes who do not have underlying nutritional deficiencies.

Treatment

Insulin is essential for control of blood glucose levels in type 1 diabetes. Good blood glucose control is the best way to prevent major complications in type 1 diabetes, including those that affect the kidneys, eyes, nerve pathways, and blood vessels. Intensive insulin treatment in early diabetes may even help preserve any residual insulin secretion for at least 2 years.

However, there are some significant problems with intensive insulin therapy.

A diet plan that matches for insulin administration and supplies healthy foods is extremely important. Pancreas transplantation may eventually be considered for people who cannot control glucose levels without frequent episodes of severe hypoglycemia.

Regimens for Intensive Insulin Treatment

The goal of intensive insulin therapy is to keep blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible, while avoiding episodes of hypoglycemia.

Blood glucose goals before meals (normal is less than 100 mg/dL):

Peak postprandial goal: Less than 180 mg/dL for adults and children.

Blood glucose goals at bedtime:

For people with type 2 diabetes, insulin therapy may consist of one or two daily insulin injections, one daily blood sugar test, and visits to the health care team every 3 months. However, for better control of blood glucose in type 1 diabetes, intensive management is usually required. The regimen is complicated although newer insulin forms may make it easier.

There are two components to insulin administration:

In achieving insulin control the person must also take other steps:

Because of the higher risk for hypoglycemia in children, doctors recommend that intensive insulin treatment be used very cautiously in children under age 13 years and not at all in very young children.

Types of Insulin

Insulin cannot be taken orally because the body's digestive juices destroy it. Injections of insulin under the skin are the most common way to administer the medications (inhaled insulin has been available, but is used rarely). The timing and frequency of insulin injections depend upon a number of factors:

Rapid-Acting Analog Insulin

Insulin lispro (Humalog), insulin glulisine (Apidra) and insulin aspart (NovoRapid, NovoLog) lower blood sugar very quickly. Insulin peaks 30 to 60 minutes after injection and continues to have some effect for about 4 hours. The short duration reduces the risk for hypoglycemic events after eating (postprandial hypoglycemia). Optimal timing for administering this insulin is about 15 minutes before a meal. But it can also be taken immediately after a meal (within 30 minutes) for people with nausea or gastroparesis. A new ultra-rapid formulation of insulin aspart has recently become available (Fiasp).

Regular Insulin

Regular insulin begins to act 30 minutes after injection, reaches its peak around 2 hours, and lasts about 6 to 8 hours. Regular insulin may be administered before a meal and may be better for high-fat meals. This insulin is not used as frequently for meal-time insulin as rapid-acting analog insulin.

Intermediate Insulin

NPH (Neutral Protamine Hagedorn) insulin is the standard intermediate form. It works within 2 to 4 hours, peaks 4 to 8 hours later, and lasts up to 14 hours. Lente (insulin zinc) is another intermediate insulin. The main advantage of these insulins is low cost.

Basal Insulin

Long-acting basal insulins, such as insulin glargine (Lantus), degludec (Tresiba), and insulin detemir (Levemir) are released slowly. Long-acting insulin does not peak for most people. It starts working in 2 to 4 hours and lasts as long as 36 hours (degludec), 24 hours (glargine), or 18 hours (detemir).

Combinations

Regimens generally include both rapid-acting and basal forms of insulin to try to match the natural insulin secretion. Often basal insulin is injected once or twice a day (about 12 hours apart). Rapid-acting analog insulin is taken before every meal and sometimes with larger snacks. Combination of two types of insulin combined in one injection is available This can reduce the number of injections, but makes the dosing less adjustable and often make good blood glucose control difficult except for people with very regimented daily schedules. Not all types of insulin can be combined in one injection.

Insulin Pens

Insulin pens, which contain cartridges of insulin, have been available for some time, although they are still more expensive than vials of insulin. These prefilled disposable pens are more portable, do not carry the stigma of a syringe, and are easier and more convenient for people. It is often easier for people to take meal-time insulin when they are away from home. For people with type 1 diabetes taking small amounts of insulin using insulin pens may cause less waste as pens contain only 300u of insulin while a vial contains 1,000u of insulin.

Inhaled Insulin

Afrezza is an inhaled form of fast-acting insulin. Afrezza is taken before meals and is designed for adult people who need mealtime insulin to help control hyperglycemia in between meals. The ability to adjust dosage is limited with inhaled insulin. Afrezza is not a substitute for long-acting insulin. People with type 1 diabetes must use it in combination with a long-acting insulin. Afrezza should not be used by people who smoke or those with long-term (chronic) lung diseases such as asthma or COPD.

The FDA will continue to examine whether Afrezza increases the risk for lung impairment or cancer, and whether it is appropriate for children. A previous form of inhaled insulin was withdrawn from the market because of changes in lung function and modest interest from people with diabetes.

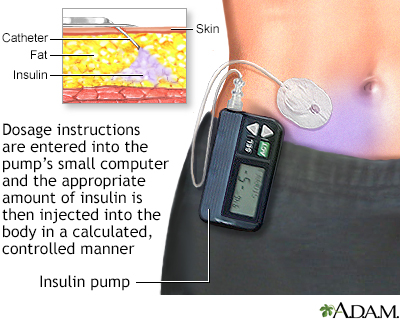

Insulin Pumps

An insulin pump can improve blood glucose control and quality of life with fewer hypoglycemic episodes than multiple injections. The pumps correct for the "dawn phenomenon" (sudden rise of blood glucose in the morning) and allow quick reductions for specific situations, such as exercise. A number of different brands are available.

The typical pump is about the size of a pager and has a digital display. Some are worn externally and are programmed to deliver insulin through a catheter under the skin. They generally use rapid-acting insulin, the most predictable type. They work by administering a small amount of insulin continuously (the basal rate) and a higher dose (a bolus dose) when food is eaten.

Although learning to use the pump can be complicated at first, most people find over time that the devices are fairly easy to use. Adults, adolescents, and school children use insulin pumps and even very young children (ages 2 to 7 years) are able to successfully use them.

The catheter at the end of the insulin pump is inserted through a needle into the abdominal fat of a person with diabetes. Dosage instructions are entered into the pump's small computer, and the appropriate amount of insulin is then injected into the body in a calculated, controlled manner.

To achieve good blood sugar control, people and parents of children must undergo some training. The person and doctor must determine the amount of insulin used. It is not automatically calculated. This requires an initial learning period, including understanding insulin needs over the course of the day and in different situations (before exercise and driving) and knowledge of carbohydrate counting. Frequent blood testing is very important, particularly during the training period.

Insulin pumps are more expensive than insulin shots and occasionally have some complications, such as blockage in the device or skin irritation at the infusion site. Despite early concerns, pumps do not appear to increase the risk of ketoacidosis.

The main advantages of insulin pump use are the ability to adjust basal rates during the day, the bolus wizard which helps calculate the right dose of insulin to match a meal, not having to carry separate supplies, and the ability to combine the pump with a CGM sensor that can give warnings and alerts. Despite certain challenges, research continues to progress on a "closed-loop" system that combines an insulin pump (and often a pump with a different hormone called glucagon) with a continuous glucose meter to form an artificial pancreas.

A disadvantage of insulin pump use for some people (often teenagers and young adults) with diabetes is that you are always wearing the pump and it can be visible to other people.

Supplementary Medications for Hyperglycemia

Pramlintide (Symlin) is an injectable drug that is used to help control postprandial hyperglycemia, the sudden increase in blood sugar after a meal. Pramlintide is injected before meals and can help lower blood sugar levels in the 3 hours after meals. Pramlintide is used in addition to insulin for people who take insulin regularly, but still need better blood sugar control. Pramlintide and insulin are the only two drugs approved for treatment of type 1 diabetes. Pramlintide is indicated only for adults.

Pramlintide is a synthetic form of amylin, a hormone that is related to insulin. Side effects may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, fatigue, and dizziness. People with type 1 diabetes have an increased risk of severe low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) that may occur within 3 hours following a pramlintide injection. This drug should not be used if people have trouble knowing when their blood sugar is low or have slow stomach emptying (gastroparesis).

Metformin (Glucophage, generic) is an oral medication used commonly in people with type 2 diabetes. However, some people with type 1 diabetes may be (or become) overweight or obese and are relatively insulin resistant. Metformin can decrease insulin needs and prevent weight gain in people with insulin resistance.

Liraglutide (Victoza) is an injectable medication used frequently in people with type 2 diabetes. This medication has also been used in people with type 1 diabetes and research studies are still evaluating the benefits of this medication in these people.

Treatment of Complications

High Blood Pressure and Heart Disease

All people with diabetes and high blood pressure should adopt lifestyle changes. These include weight reduction (when needed), following the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) or similar diet, smoking cessation, limiting alcohol intake, and limiting salt intake to no more than 1,500 to 2,300 mg of sodium per day. (Exact sodium limits are determined on an individual basis; discuss with your doctor what an appropriate sodium limit is for you.)

High Blood Pressure Control

In general, people with diabetes should strive for blood pressure levels of less than 140/90 mm Hg (systolic/diastolic). Lowering blood pressure to 130/80 mm Hg may be recommended for those at risk of cardiovascular disease. It is recommended that people with diabetes and hypertension monitor their blood pressure at home on a regular basis.

People with diabetes and high blood pressure need an individualized approach to drug treatment, based on their particular health profile. Dozens of anti-hypertensive drugs are available. The most beneficial fall into the following categories:

Nearly all people who have diabetes and high blood pressure should take an ACE inhibitor or ARB (angiotensin receptor blocker) as part of their regimen for treating their hypertension. These drugs help prevent heart and kidney damage, and are recommended as the best first-line drugs for people with diabetes and hypertension.

Improving Cholesterol and Lipid Levels

Abnormal cholesterol and lipid levels are common in diabetes. High LDL ("bad") cholesterol should always be lowered. But people with diabetes also often have additional harmful imbalances, including low HDL ("good") cholesterol and high triglycerides.

Treatment recommendations are made on an individual basis, considering lipid profiles taken as a whole (LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides), as well as other risk factors. In general, adult people should aim for LDL levels below 100 mg/dL, HDL levels over 50 mg/dL, and triglyceride levels below 150 mg/dL. The American Diabetes Association considers statin therapy for lowering LDL levels appropriate for most people with type 1 diabetes who are ages 40 to 75 years old. For people younger than age 40 ages, statin therapy needs to be considered on an individual basis.

Lifestyle changes for cholesterol management in people with diabetes focus on:

For medications, statins are the best cholesterol-lowering drugs. They include atorvastatin (Lipitor, generic), lovastatin (Mevacor, generic), pravastatin (Pravachol, generic), simvastatin (Zocor, Simcor, Vytorin, and generics), fluvastatin (Lescol, generic), rosuvastatin (Crestor), and pitavastatin (Livalo).

These drugs are very effective for lowering LDL cholesterol levels. However, they may increase blood glucose levels in some people, particularly when taken in high doses. Still, statin drugs are considered generally safe. If one statin drug does not work or has side effects, the doctor may recommend switching to a different statin.

The primary safety concern with statins has involved myopathy, an uncommon condition that can cause muscle damage and, in some cases, muscle and joint pain. A routine blood test for creatine kinase can monitor for this side effect. A specific myopathy called rhabdomyolysis can lead to kidney failure. People with diabetes and risk factors for myopathy should be monitored for muscle symptoms. Strategies for addressing the muscle side effects of statins include adjusting the dose of statin and switching to either another type of statin, combination, or non-statin lipid-lowering drugs.

Ezetimibe may be used in combination with a statin drug for those with recent acute coronary syndrome. A new type of medication called a PCSK9 inhibitor is now available to reduce cholesterol levels in people with genetic causes of high cholesterol levels. This medication is given as an injection under the skin.

Aspirin for Heart Disease Prevention

For people with diabetes who have additional heart disease risk factors, taking a daily aspirin can reduce the risk for blood clotting and may help protect against heart attacks. (There is not enough evidence to indicate that aspirin prevention is helpful for people at lower risk.) These risk factors include a family history of heart disease, high blood pressure, smoking, unhealthy cholesterol levels, or excessive urine levels of the protein albumin. The recommended dose is 75 to 162 mg/day. Talk to your doctor, particularly if you are at risk for aspirin side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers.

Treatment of Retinopathy

People with severe diabetic retinopathy or macular edema (swelling of the retina) should see an eye specialist who is experienced in the management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Once damage to the eye develops, laser or photocoagulation eye surgery may be needed. Laser surgery can help reduce vision loss in high-risk people. Drug therapy with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is also recommended for treatment of diabetic macular edema.

Treatment of Foot Ulcers

About a third of foot ulcers will heal within 20 weeks with good wound care treatments. Some treatments are as follows:

Other Treatments for Foot Ulcers

Doctors are also using or investigating other treatments to heal ulcers. These include:

Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathy

The only FDA-approved drugs for treating neuropathy are pregabalin (Lyrica) and duloxetine (Cymbalta). Other drugs and treatments are used on an off-label basis.

The American Academy of Neurology's (AAN) guidelines for treating painful diabetic neuropathy recommend:

Treatments for Other Complications of Neuropathy

Neuropathy also impacts other functions, and treatments are needed to reduce their effects. If diabetes affects the nerves in the autonomic nervous system, then abnormalities of blood pressure control and bowel and bladder function may occur. Erythromycin, domperidone (Motilium), or metoclopramide (Reglan) may be used to relieve delayed stomach emptying caused by neuropathy (diabetic gastroparesis). People need to watch their nutrition if the problem is severe.

Erectile dysfunction is also associated with neuropathy. Studies indicate that phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) drugs, such as sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis), and avanafil (Stendra) are safe and effective, at least in the short term, for many people with diabetes. Typical side effects are minimal but may include headache, flushing, and upper respiratory tract and flu-like symptoms. People who take nitrate medications for heart disease cannot use PDE-5 drugs. Recent studies have shown that testosterone replacement may also improve erectile function in older people that have low testosterone levels in the blood.

Treatment of Kidney Problems

Tight control of blood sugar and blood pressure is essential for preventing the onset of kidney disease and for slowing the progression of the disease.

ACE inhibitors are the best class of blood pressure medications for delaying kidney disease and slowing disease progression in people with diabetes. Angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) are also very helpful.

Anemia

Anemia is a common complication of end-stage kidney disease. People on dialysis usually need injections of erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs to increase red blood cell counts and control anemia. However, these drugs -- darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp) and epoetin alfa (Epogen and Procrit) -- can increase the risk of blood clots, stroke, heart attack, and heart failure in people with end-stage kidney disease when they are given at higher than recommended doses.

End-stage kidney disease, anemia, and treatment with medications that mimic erythropoietin change the relationship between A1c and blood glucose. In this situation, the A1c is not a reliable indicator of good glucose control. People with end-stage kidney disease are often at greater risk of hypoglycemia, particularly fasting hypoglycemia during the night or early morning. People with kidney disease taking insulin to control their blood sugars often need to reduce their insulin doses as their kidney disease progresses. Other tests such as fructosamine can be used to monitor blood sugar control instead of A1c.

The FDA recommends that people with end-stage kidney disease who receive erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs should:

Treatment of Diabetes During Pregnancy

Some recommendations for preventing pregnancy complications include:

Home Management

Monitoring Glucose (Blood Sugar) Levels

Both low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) are of concern for people who take insulin. It is important, therefore, to carefully monitor blood glucose levels. In general, people with type 1 diabetes need to take readings 4 or more times a day.

The American Diabetes Association recommends that people on multiple dose insulin should test their blood sugar:

People should aim for the following measurements:

Different goals may be required for specific individuals, including pregnant women, very old and very young people, and those with accompanying serious medical conditions.

Finger-Prick Test (point-of-care)

A typical blood sugar test includes the following:

Home monitors are less accurate than laboratory monitors and many do not meet the standards of the American Diabetes Association. However, they are usually accurate enough to indicate when blood sugar is too low.

To monitor the amount of glucose within the blood, a person with diabetes should test their blood regularly. The procedure is quite simple and can often be done at home.

Some simple procedures may improve accuracy, such as:

Continuous Glucose Monitoring Systems

CGM systems use a small plastic sensor inserted under the skin of the abdomen to monitor glucose levels every 5 minutes. Depending on the system, CGMs measure glucose levels for up to 14 days and some can sound an alarm if glucose levels are too high or low.

These devices used to only work when used along with traditional finger-stick testing and glucose. Newer CGM sensors do not need a finger-stick blood glucose to be accurate. Some CGM systems are now approved for children as well as adults. The American Diabetes Association recommends CGM as a useful tool for people with type 1 diabetes.

The cost and insurance coverage for CGM has improved in the last five years, and now almost all people with type 1 diabetes should have access to these important devices.

Urine Tests