Newborn jaundice - discharge

Your baby has been treated in the hospital for newborn jaundice. This article tells you what you need to know when your baby comes home.

Newborn jaundice

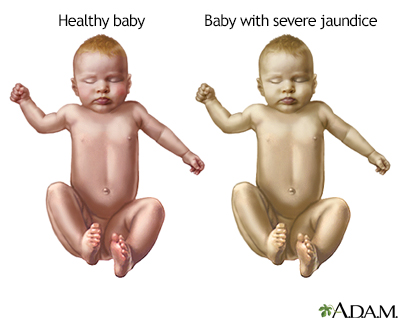

Newborn jaundice occurs when a baby has a high level of bilirubin in the blood. Bilirubin is a yellow substance that the body creates when it replac...

Video Transcript

Newborn jaundice - Animation

Are your newborn baby’s skin or eyes yellow? Is she extremely tired and doesn’t want to eat? Your baby may have jaundice. Newborn jaundice happens when your baby has high levels of bilirubin in her blood. This yellow pigment is created in the body during the normal recycling of old red blood cells.The liver helps break bilirubin down so it can be removed from the body in the stool. Before a baby is born, the placenta removes the bilirubin from your baby so it can be processed by your liver. Right after birth, the baby’s own liver takes over the job, but it can take time. Most babies have some jaundice. It usually appears between the second and third day after birth.Often babies get a screening test in the first 24 hours of life to predict if they are likely to develop jaundice. Your baby’s doctor will also watch for signs of jaundice at the hospital, and during follow-up visits after your baby goes home. If your baby seems to have significant jaundice, the doctor will test the bilirubin levels in her blood.So, how do you treat newborn jaundice? Jaundice usually goes away on its own, so treatment is usually not necessary. If your baby’s bilirubin level is too high or rising too quickly, however, she may need treatment.You’ll need to keep the baby well hydrated with breast milk or formula. Feeding up to 12 times a day will encourage frequent bowel movements, which help to remove the bilirubin.If your baby needs treatment in the hospital, she may be placed under special blue lights that help break down bilirubin in the baby’s skin. This treatment is called phototherapy. If your baby’s bilirubin level isn’t rising too quickly, you can also do phototherapy at home with a fiber optic blanket that contains tiny bright lights. For most babies, it takes about a week or two for jaundice to go away.

When Your Child Was in the Hospital

Your baby has newborn jaundice. This common condition is caused by high levels of bilirubin in the blood. Your child's skin and sclera (whites of their eyes) will look yellow.

Some newborns need to be treated before they leave the hospital. Others may need to go back to the hospital when they are a few days old. Treatment in the hospital most often lasts 1 to 2 days. Your child needs treatment when their bilirubin level is too high or rising too quickly.

To help break down the bilirubin, your child will be placed under bright lights (phototherapy) in a warm, enclosed bed. The infant will wear only a diaper and special eye shades. Your baby may have an intravenous (IV) line to give them fluids.

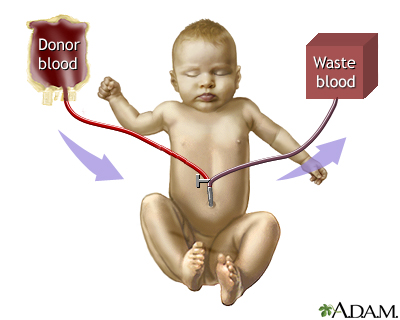

Rarely, your baby may need treatment called a double volume blood exchange transfusion. This is used when the baby's bilirubin level is very high.

Unless there are other problems, your child will be able to feed (by breast or bottle) normally. Your child should feed every 2 to 2 ½ hours (10 to 12 times a day).

The health care provider may stop phototherapy and send your child home when their bilirubin level is low enough to be safe. Your child's bilirubin level will need to be checked in the provider's office, 24 hours after therapy stops, to make sure the level is not rising again.

Possible side effects of phototherapy are watery diarrhea, dehydration, and skin rash that will go away once the therapy stops.

What to Expect at Home

If your child did not have jaundice at birth but now has it, you should call your provider. Bilirubin levels are generally the highest when a newborn is 3 to 5 days old. Many web-based applications can quickly detect bilirubin levels in newborns without requiring blood tests. These applications use a cellphone camera and a color card to check bilirubin levels. These applications can help parents monitor the bilirubin levels of their newborn at home and seek immediate care if necessary.

If the bilirubin level is not too high or not rising quickly, you can do phototherapy at home with a fiber optic blanket, which has tiny bright lights in it. You may also use a bed that shines light up from the mattress. A nurse will come to your home to teach you how to use the blanket or bed and to check on your child.

The nurse will return daily to check your child's:

- Weight

- Intake of breast milk or formula

- Number of wet and poopy (stool) diapers

- Skin, to see how far down (head to toe) the yellow color goes

- Bilirubin level

You must keep the light therapy on your child's skin and feed your child every 2 to 3 hours (10 to 12 times a day). Feeding prevents dehydration and helps bilirubin leave the body.

Therapy will continue until your baby's bilirubin level lowers enough to be safe. Your baby's provider will want to check the level again in 2 to 3 days.

If you are having trouble breastfeeding, contact a breastfeeding nurse specialist or lactation consultant.

When to Call the Doctor

Contact your baby's provider if the infant:

- Has a yellow color that goes away, but then returns after treatment stop

- Has a yellow color that lasts for more than 2 to 3 weeks

Also contact your baby's provider if you have concerns, if the jaundice is getting worse, or the baby:

- Is lethargic (hard to wake up), less responsive, or fussy

- Refuses the bottle or breast for more than 2 feedings in a row

- Is losing weight

- Has watery diarrhea

Reviewed By

Charles I. Schwartz, MD, FAAP, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, General Pediatrician at PennCare for Kids, Phoenixville, PA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

BiliTool TM website. bilitool.org. Updated May 2024. Accessed April 7, 2025.

Kaplan M, Wong RJ, Bensen R, Sibley E, Stevenson DK. Neonatal jaundice and liver diseases. In: Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, eds. Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 95.

Kliegman RM. Digestive system disorders. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 134.

Rozance PJ, Wright CJ. The neonate. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 25.