Mitral valve prolapse

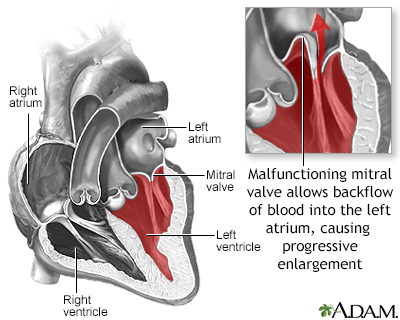

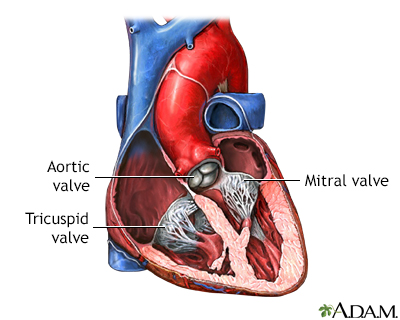

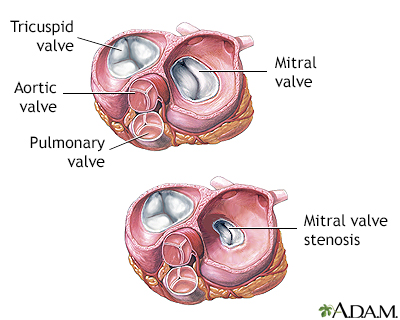

Barlow syndrome; Floppy mitral valve; Myxomatous mitral valve; Billowing mitral valve; Systolic click-murmur syndrome; Prolapsing mitral leaflet syndrome; Chest pain - mitral valve prolapseMitral valve prolapse is a heart problem involving the mitral valve, which separates the upper and lower chambers of the left side of the heart. In this condition, the valve does not close normally.

-

Causes

The mitral valve helps blood on the left side of the heart flow in one direction. It closes to keep blood from moving backwards when the heart beats (contracts).

Mitral valve prolapse is the term used when the valve does not close properly. It can be caused by many different things.

In most cases, it is harmless. The problem generally does not affect health and most people with the condition are not aware of it. In a small number of cases, the prolapse can cause blood to leak backwards. This is called mitral regurgitation.

Mitral valve prolapse often affects thin women who may have minor chest wall deformities, scoliosis, or other disorders. Some forms of mitral valve prolapse seem to be passed down through families (inherited).

Mitral valve prolapse is also seen with some connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome and other rare genetic disorders.

It is also sometimes seen in isolation in people who are otherwise normal.

-

Symptoms

Many people with mitral valve prolapse Do not have symptoms. A group of symptoms sometimes found in people with mitral valve prolapse has been called "mitral valve prolapse syndrome," and includes:

- Chest pain (not caused by coronary artery disease or a heart attack)

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Panic attacks

- Sensation of feeling the heart beat (palpitations)

- Shortness of breath with activity or when lying flat (orthopnea)

The exact relationship is between these symptoms and the valve problem is not clear. Some of the findings may be coincidental.

When mitral regurgitation occurs, symptoms may be related to the leaking, particularly when severe.

-

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will perform a physical exam and use a stethoscope to listen to your heart and lungs. The provider may feel a thrill (vibration) over the heart and hear a heart murmur and an extra sound (midsystolic click). The murmur usually gets longer and louder when you stand up.

Blood pressure is most often normal.

Echocardiogram is the most common test used to diagnose mitral valve prolapse. The following tests may also be used to diagnose mitral valve prolapse or a leaky mitral valve or complications from those conditions:

- Cardiac catheterization

- Chest x-ray

- Heart CT scan

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) may show arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation

- MRI scan of the heart

-

Treatment

Most of the time, there are few or no symptoms and treatment is not needed.

In the past, most people with heart valve problems were given antibiotics before dental work or procedures such as colonoscopy to prevent an infection in the heart. However, antibiotics are now used much less often. Check with your provider to see if you need antibiotics.

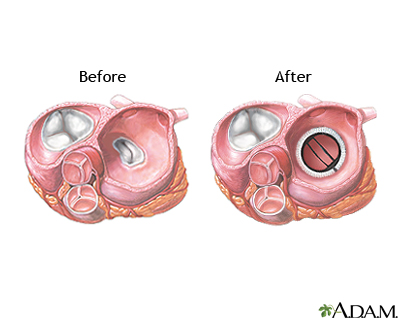

There are many heart medicines that may be used to treat aspects of this condition. However, most people will not need any treatment. You may need surgery to repair or replace your mitral valve if it becomes very leaky (regurgitation), and if the leakiness also causes symptoms. However, this may not occur. You may need mitral valve repair or replacement if:

- Your symptoms get worse.

- The left ventricle of your heart is enlarged.

- Your heart function gets worse.

-

Outlook (Prognosis)

Most of the time, mitral valve prolapse is harmless and does not cause symptoms. Symptoms that do occur can be treated and controlled with medicine or surgery.

Some abnormal heartbeats (arrhythmias) in people with mitral valve prolapse can be life threatening. If the valve leakage becomes severe, your outlook may be similar to that of people who have mitral regurgitation from any other cause.

-

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have:

- Chest discomfort, palpitations, or fainting spells that get worse

- Long-term illnesses with fevers

References

Carabello BA, Kodali S. Valvular heart disease. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 60.

Hahn RT, Bonow RO. Mitral regurgitation. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 76.

Writing Committee Members, Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162(2):e183-e353. PMID: 33972115 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33972115/.