Community-acquired pneumonia in adults

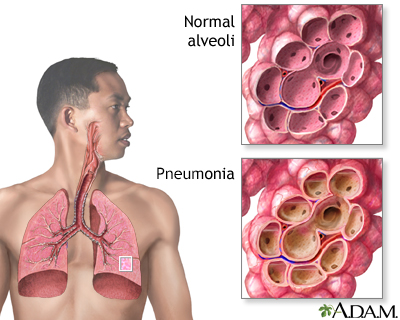

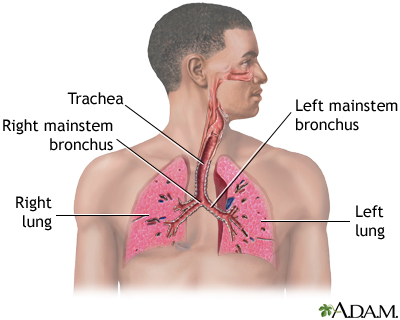

Bronchopneumonia; Community-acquired pneumonia; CAPPneumonia is inflamed or swollen lung tissue due to infection with a germ.

This article covers community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). This type of pneumonia is found in people who have not recently been in the hospital or another health care facility such as a nursing home or rehab facility. Pneumonia that affects people in or recently released from a health care facility, such as hospitals, is called hospital-acquired pneumonia (or health care-associated pneumonia).

-

Causes

Pneumonia is a common illness that affects millions of people each year in the United States. Germs called bacteria, viruses, and fungi may cause pneumonia. In adults, bacteria are the most common cause of pneumonia.

Ways you can get pneumonia include:

- Bacteria and viruses living in your nose, sinuses, or mouth may spread to your lungs.

- You may breathe some of these germs directly into your lungs.

- You breathe in (inhale) food, liquids, vomit, or fluids from the mouth into your lungs (aspiration pneumonia).

Pneumonia can be caused by many types of germs.

- The most common type of bacteria is Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus).

- Atypical pneumonia, often called walking pneumonia, is caused by other bacteria.

- A fungus called Pneumocystis jirovecii can cause pneumonia in people whose immune system is not working well, especially people with advanced HIV infection.

- Viruses, such as the flu (influenza) virus, and most recently SARS-CoV-2 (which causes COVID-19), are also common causes of pneumonia.

Risk factors that increase your chance of getting pneumonia include:

- Chronic lung disease (COPD, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis)

- Cigarette smoking

- Dementia, stroke, brain injury, cerebral palsy, or other brain disorders

- Immune system problem (during cancer treatment, or due to HIV/AIDS, organ transplant, or other diseases)

- Other serious illnesses, such as heart disease, liver cirrhosis, or diabetes

- Recent surgery or trauma

- Surgery to treat cancer of the mouth, throat, or neck

-

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will listen for crackles or abnormal breath sounds when listening to your chest with a stethoscope. Tapping on your chest wall (percussion) helps your provider listen and feel for abnormal sounds in your chest.

If pneumonia is suspected, your provider will likely order a chest x-ray.

Other tests that may be ordered include:

- Arterial blood gases to see if enough oxygen is getting into your blood from the lungs.

- Blood and sputum cultures to look for the germ that may be causing the pneumonia.

- CBC to check white blood cell count.

- CT scan of the chest.

- Bronchoscopy in which a flexible tube with a lighted camera on the end passed down to your lungs in selected cases.

- Thoracentesis which involves removing fluid from the space between the outside lining of the lungs and the chest wall.

- Nasopharyngeal swab to assess for viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2.

-

Treatment

Your provider must first decide whether you need to be in the hospital. If you are treated in the hospital, you will receive:

- Fluids and antibiotics (or antivirals) through your veins

- Oxygen therapy

- Breathing treatments (possibly)

If you are diagnosed with a bacterial form of pneumonia, it is important that you are started on antibiotics very soon after you are admitted. If you have viral pneumonia, you will not receive antibiotics. This is because antibiotics do not kill viruses. You may receive other medicines, such as antivirals, if you have the flu or other type of viral pneumonia.

You are more likely to need to be admitted to the hospital if you:

- Have another serious medical problem

- Have severe symptoms

- Are unable to care for yourself at home, or are unable to eat or drink

- Are 65 years or older

- Have been taking antibiotics at home and are not getting better

Most people can be treated at home. If so, your provider may tell you to take medicines such as antibiotics. Antibiotics are usually prescribed for 3 to 5 days, although sometimes they may be used for 2 weeks or more.

When taking antibiotics:

- Do not miss any doses. Take the medicine until it is gone, even when you start to feel better.

- Do not take cough medicine or cold medicine unless your provider says it is OK. Coughing helps your body get rid of mucus from your lungs.

Breathing warm, moist (wet) air helps loosen the sticky mucus that may make you feel like you are choking. These things may help:

- Place a warm, wet washcloth loosely over your nose and mouth.

- Fill a humidifier with warm water and breathe in the warm mist.

- Take a couple of deep breaths 2 or 3 times every hour. Deep breaths will help open up your lungs.

- Tap your chest gently a few times a day while lying with your head lower than your chest. This helps bring up mucus from the lungs so that you can cough it out.

Drink plenty of liquids, as long as your provider says it is OK.

- Drink water, juice, or weak tea

- Drink at least 6 to 10 cups (1.4 to 2.4 liters) a day

- Do not drink alcohol

Get plenty of rest when you go home. If you have trouble sleeping at night, take naps during the day.

-

Outlook (Prognosis)

With treatment, most people improve rapidly and feel nearly back to normal within 2 weeks. Older adults or very sick people may need longer treatment.

Those who may be more likely to have complicated pneumonia include:

- Older adults

- People whose immune system does not work well

- People with other serious medical problems, such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or cirrhosis of the liver

In all of the above conditions, pneumonia can lead to serious illness or even death, if it is severe.

In rare cases, more serious problems may develop, including:

- Life-threatening changes in the lungs that require a breathing machine

- Fluid around the lung (pleural effusion)

- Infected fluid around the lung (empyema)

- Lung abscesses

After treatment, your provider may order another x-ray. This is to make sure your lungs are clear. But it may take many weeks for your x-ray to clear up. You will likely feel better before the x-ray clears up.

-

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have:

- Cough that brings up bloody or rust-colored mucus

- Breathing (respiratory) symptoms that get worse

- Chest pain that gets worse when you cough or breathe in

- Fast or painful breathing

- Night sweats or unexplained weight loss

- Shortness of breath, shaking chills, or persistent fevers

- Signs of pneumonia along with a weak immune system (such as with HIV or chemotherapy)

- Worsening of symptoms after initial improvement

- Conditions (such as heart or lung disease, or diabetes) that increase your chance of having severe pneumonia

-

Prevention

You can help prevent pneumonia by following the measures below.

Wash your hands often, especially:

- Before preparing and eating food

- After blowing your nose

- After using the toilet

- After changing a baby's diaper

- After coming in contact with people who are sick

Avoid coming into contact with people who are sick.

Do not smoke. Tobacco damages your lung's ability to fight infection.

Vaccines may help prevent some types of pneumonia. Be sure to get the following vaccines:

- Flu vaccine can help prevent pneumonia caused by the flu virus.

- Pneumococcal vaccine lowers your chances of getting pneumonia from Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- COVID-19 vaccine can help prevent severe pneumonia from SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Vaccines are even more important for older adults and people with heart disease, diabetes, asthma, emphysema, HIV, cancer, people with organ transplants, or other long-term conditions.

References

Baden LR, Griffin MR, Klompas M. Overview of pneumonia. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 85.

Daly JS, Ellison RT. Acute pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 67.

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. PMID: 31573350 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31573350/.