Hiatal hernia

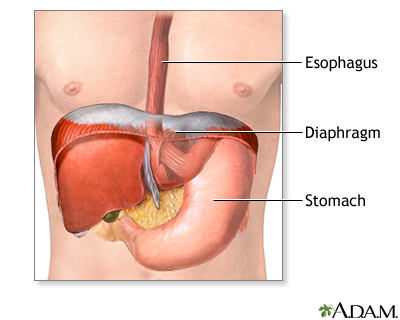

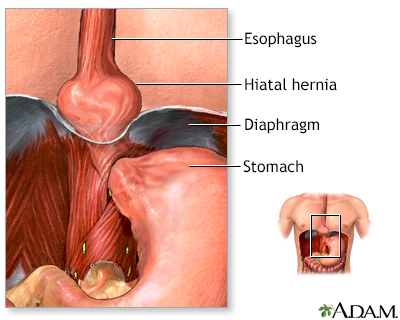

Hernia - hiatalHiatal hernia is a condition in which part of the stomach extends through an opening of the diaphragm into the chest. The diaphragm is the sheet of muscle that divides the chest from the abdomen.

Causes

The exact cause of hiatal hernia is not known. The condition may be due to weakness of the supporting tissue. Your risk for the problem goes up with age, obesity, and smoking. Hiatal hernias are very common. The problem occurs often in people over 50 years of age.

Obesity

Overweight and obesity mean having a weight than is higher than what is healthy for a given height. A person may be overweight from extra muscle, bo...

This condition may be linked to reflux (backflow) of gastric acid from the stomach into the esophagus.

Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which the stomach contents leak backward from the stomach into the esophagus (food pipe). F...

Children with this condition are most often born with it (congenital). In infants, it often occurs with gastroesophageal reflux.

Gastroesophageal reflux

Anti-reflux surgery is surgery to tighten the muscles at the bottom of the esophagus (the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach). Pro...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleSymptoms

Symptoms may include:

-

Chest pain

Chest pain

Chest pain is discomfort or pain that you feel anywhere along the front of your body between your neck and upper abdomen.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Heartburn, worse when bending over or lying down

Heartburn

Heartburn is a painful burning feeling just below or behind the breastbone. Most of the time, it comes from the esophagus. The pain often rises in ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Swallowing difficulty

A hiatal hernia by itself rarely causes symptoms. Pain and discomfort are due to the upward flow of stomach acid, air, or bile.

Exams and Tests

Tests that may be used include:

-

Barium swallow x-ray

Barium swallow x-ray

An upper GI and small bowel series is a set of x-rays taken to examine the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. Barium enema is a different test ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

EGD

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a test to examine the lining of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine (the duodenum)....

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Treatment

The goals of treatment are to relieve symptoms and prevent complications. Treatments may include:

- Medicines to control stomach acid

-

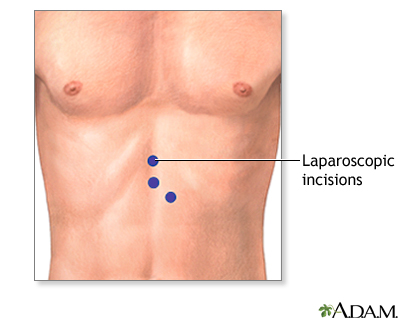

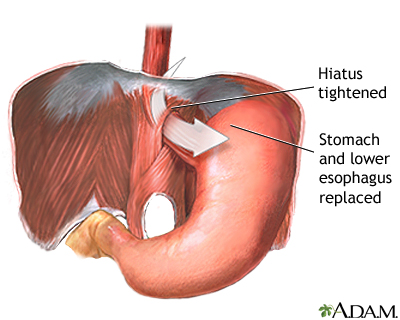

Surgery to repair the hiatal hernia and prevent reflux

Surgery to repair the hiatal hernia

Anti-reflux surgery is a treatment for acid reflux, also known as GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease). GERD is a condition in which food or stoma...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Other measures to reduce symptoms include:

- Avoiding large or heavy meals

- Not lying down or bending over right after a meal

- Reducing weight and not smoking

- Raising the head of the bed 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 centimeters)

If medicines and lifestyle measures do not help control symptoms, you may need surgery.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Treatment can relieve most symptoms of hiatal hernia.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Pulmonary (lung) aspiration

Aspiration

Aspiration means to draw in or out using a sucking motion. It has two meanings:Breathing in a foreign object (for example, sucking food into the air...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Slow bleeding and iron deficiency anemia (due to a large hernia)

Iron deficiency anemia

Anemia is a condition in which the body does not have enough healthy red blood cells. Red blood cells provide oxygen to body tissues. There are man...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Strangulation (closing off) of the hernia (very uncommon)

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your health care provider if:

- You have symptoms of a hiatal hernia.

- You have a hiatal hernia and your symptoms get worse or do not improve with treatment.

- You develop new symptoms.

Prevention

Controlling risk factors such as obesity may help prevent hiatal hernia.

References

Battafarano RJ. Esophagus: Management of paraesophageal hernia repair. In: Cameron J, ed. Current Surgical Therapy. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:3-80.

Falk GW, Katzka DA. Diseases of the esophagus. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 129.

Lord KA, Lippincott J. Hiatal hernia. In: Ferri FF, ed. Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:749.e2-749.e5.

Yates RB, Oelschlager BK. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and hiatal hernia. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:chap 43.

-

Hiatal hernia - X-ray - illustration

This X-ray shows the upper portion of the stomach protruding through the diaphragm (hiatal hernia).

Hiatal hernia - X-ray

illustration

-

Hiatal hernia - illustration

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of the stomach protrudes up into the chest through the sheet of muscle called the diaphragm. This may result from a weakening of the surrounding tissues and may be aggravated by obesity and/or smoking.

Hiatal hernia

illustration

-

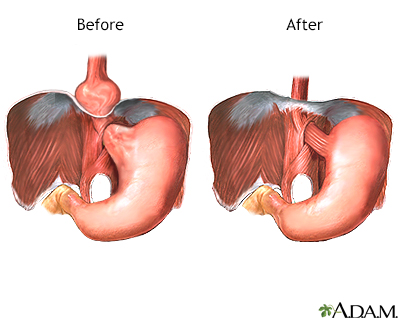

Hiatal hernia repair - series

Presentation

-

Hiatal hernia - X-ray - illustration

This X-ray shows the upper portion of the stomach protruding through the diaphragm (hiatal hernia).

Hiatal hernia - X-ray

illustration

-

Hiatal hernia - illustration

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of the stomach protrudes up into the chest through the sheet of muscle called the diaphragm. This may result from a weakening of the surrounding tissues and may be aggravated by obesity and/or smoking.

Hiatal hernia

illustration

-

Hiatal hernia repair - series

Presentation

Review Date: 5/2/2023

Reviewed By: Michael M. Phillips, MD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.