Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter

Auricular fibrillation; AFib; A-fib; Afib; Supraventricular arrhythmia; AF; AFLAtrial fibrillation (AFib) and atrial flutter are common types of abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias) which affect the upper chambers (atria) of the heart.

Arrhythmias

An arrhythmia is a disorder of the heart rate (pulse) or heart rhythm. The heart can beat too fast (tachycardia), too slow (bradycardia), or irregul...

In atrial flutter, the heart beats too fast, but often continues to contract in a regular rhythm. AFib is a closely related condition in which the atria contract in a chaotic manner, or "quivers." This creates a very irregular heart rhythm that is also usually too fast. AFib and atrial flutter often occur in the same person at different times.

Causes

When working well, the 4 chambers of the heart contract (squeeze) in an organized way.

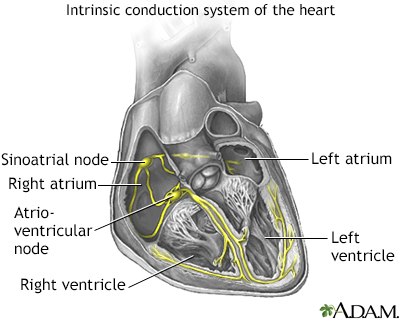

Electrical signals direct your heart to pump the right amount of blood for your body's needs. The signals begin in an area called the sinoatrial node (also called the sinus node or SA node).

In people with AFib, the electrical impulse of the heart is not regular. This is because the sinoatrial node no longer controls the sequence of heart muscle contractions (rhythm) in the upper chambers of the heart (atria).

In AFib:

- The atria do not contract in an organized pattern.

- The lower chambers of the heart (ventricles) contract in an irregular manner that is often too fast.

- As a result, the heart often cannot pump enough blood to meet the body's needs.

In people with atrial flutter, the atria beat very rapidly, but in a regular pattern.

These problems can affect both men and women. They become more common with increasing age.

Common causes of AFib include:

- Alcohol use (especially binge drinking)

- Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease

Coronary heart disease is a narrowing of the blood vessels that supply blood and oxygen to the heart. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is also called co...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Heart attack or heart bypass surgery

Heart attack

Most heart attacks are caused by a blood clot that blocks one of the coronary arteries. The coronary arteries bring blood and oxygen to the heart. ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleHeart bypass surgery

Heart bypass surgery creates a new route, called a bypass, for blood and oxygen to go around a blockage to reach your heart.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Heart failure or an enlarged heart

Heart failure

Heart failure is a condition in which the heart is no longer able to pump oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body efficiently. This causes symptom...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Heart valve disease (most often the mitral valve)

- Hypertension

Hypertension

Blood pressure is a measurement of the force exerted against the walls of your arteries as your heart pumps blood to your body. Hypertension is the ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Medicines

- Overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism)

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is a condition in which the thyroid gland makes too much thyroid hormone. The condition is often called overactive thyroid.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Pericarditis

Pericarditis

Pericarditis is a condition in which the sac-like covering around the heart (pericardium) becomes inflamed.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Sick sinus syndrome

Sick sinus syndrome

Normally, the heartbeat starts in an area in the top chambers of the heart (atria). This area is the heart's pacemaker. It is called the sinoatrial...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Symptoms

You may not be aware that your heart is not beating in a normal pattern. When symptoms are present, they may include one or more of the following:

- Pulse that feels rapid, racing, pounding or thumping, fluttering, irregular, or too slow.

- Sensation of feeling the heart beat (palpitations).

Palpitations

Palpitations are feelings or sensations that your heart is pounding or racing. They can be felt in your chest, throat, or neck. You may:Have an unpl...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Confusion.

Confusion

Confusion is the inability to think as clearly or quickly as you normally do. You may feel disoriented and have difficulty paying attention, remembe...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Dizziness, lightheadedness.

Dizziness

Dizziness is a term that is often used to describe 2 different symptoms: lightheadedness and vertigo. Lightheadedness is a feeling that you might fai...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Fainting.

Fainting

Fainting is a brief loss of consciousness due to a drop in blood flow to the brain. The episode most often lasts less than a couple of minutes and y...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Fatigue.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a feeling of weariness, tiredness, or lack of energy.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Weakness.

- Loss of ability to exercise.

- Shortness of breath and anxiety.

- Sweating.

- Chest pain or pressure, which may be a sign of a heart attack. Call 911 or the local emergency number right away if you have chest pain or pressure.

Chest pain or pressure

Chest pain is discomfort or pain that you feel anywhere along the front of your body between your neck and upper abdomen.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider may hear a fast heartbeat while listening to your heart with a stethoscope. Your pulse may feel fast, uneven, or both.

The normal heart rate is 60 to 100 beats per minute. In Afib or flutter, the heart rate may be as high as 250 to 350 beats per minute and is very often over 100 beats per minute. Blood pressure may be normal or low.

An ECG (a test that records the electrical activity of the heart) may show AFib or atrial flutter.

ECG

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is a test that records the electrical activity of the heart.

If your abnormal heart rhythm comes and goes, you may need to wear a special monitor to diagnose the problem. The monitor records the heart's rhythms over a period of time.

- Event monitor (3 to 4 weeks)

- Holter monitor (24 to 48 hours)

Holter monitor

A Holter monitor is a machine that continuously records the heart's rhythms. The monitor is worn for 24 to 48 hours during normal activity.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Patch monitor (1 to 2 weeks)

- Implanted loop recorder (extended monitoring)

Tests to find heart disease may include:

- Echocardiogram (ultrasound imaging of the heart)

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram is a test that uses sound waves to create pictures of the heart. The picture and information it produces is more detailed than a s...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Tests to examine the blood supply of the heart muscle

- Tests to study the heart's electrical system

Tests to study the heart's electrical s...

Intracardiac electrophysiology study (EPS) is a test to look at how well the heart's electrical signals are working. It is used to evaluate abnormal...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Treatment

Cardioversion treatment may be used to get the heart back into a normal rhythm right away. There are two options for treatment:

Cardioversion

Cardioversion is a method to bring an abnormal heart rhythm back to normal.

- Electric shocks to your heart

- Medicines given through a vein

These treatments may be done as emergency methods, or planned ahead of time.

Daily medicines taken by mouth are used to:

- Slow the irregular heartbeat and maintain normal heart rhythm -- These medicines may include beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, and anti-arrhythmics.

- Prevent blood clots -- Blood-thinning medicines are often given to reduce the risk of blood clots that can result from ongoing irregular heart rhythms.

- Prevent AFib from coming back -- These medicines work well in many people, but they can have serious side effects. AFib returns in many people, even while they are taking these medicines.

A procedure called radiofrequency ablation can be used to scar areas in your heart where the heart rhythm problems are triggered. This can prevent the abnormal electrical signals that cause AFib or flutter from moving through your heart. You may need a heart pacemaker after this procedure. All people with AFib will need to learn how to manage this condition at home.

Radiofrequency ablation

Cardiac ablation is a procedure that is used to scar small areas in your heart that may be involved in your heart rhythm problems. This can prevent ...

Pacemaker

A pacemaker is a small, battery-operated device. This device senses when your heart is beating too slowly. It sends a signal to your heart that mak...

Manage this condition at home

Atrial fibrillation (Afib) or flutter is a common type of abnormal heartbeat. The heart rhythm is fast and irregular. You were in the hospital to t...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticlePeople with AFib will most often need to take blood thinner medicines. These medicines are used to reduce the risk of developing a blood clot that travels in the body (and that can cause a stroke, for example). The irregular heart rhythm that occurs with AFib makes blood clots more likely to form.

Blood thinner medicines include heparin, warfarin (Coumadin), apixaban (Eliquis), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), edoxaban (Savaysa) and dabigatran (Pradaxa). Antiplatelet medicines such as aspirin or clopidogrel may also be prescribed. However, blood thinners increase the chance of bleeding, so not everyone can use them.

Heparin

Your health care provider prescribed a blood thinning medicine called heparin. It has to be given as a shot at home. A nurse or other health profess...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleWarfarin

Warfarin is a medicine that makes your blood less likely to form clots. It is important that you take warfarin exactly as you have been told. Chang...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleAspirin

Current guidelines recommend that people with coronary artery disease (CAD) receive antiplatelet therapy with either aspirin or clopidogrel. Aspirin ...

Clopidogrel

Platelets are small particles in your blood that your body uses to form clots and stop bleeding. If you have too many platelets or your platelets st...

Another stroke prevention option for people who cannot safely take these medicines are left atrial appendage occlude (LAAO) devices. These are small implants that are placed inside the heart to block off the area of the heart where most of the clots form. This limits clots from forming.

Your provider will consider your age and other medical problems when deciding which stroke prevention methods are best for you.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Treatment can often control this disorder. Many people with AFib do very well with treatment.

AFib tends to return and get worse. It may come back in some people, even with treatment.

Clots that break off and travel to the brain can cause a stroke.

Stroke

A stroke occurs when blood flow to a part of the brain stops. A stroke is sometimes called a "brain attack. " If blood flow is cut off for longer th...

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have symptoms of AFib or flutter.

Prevention

Talk to your provider about steps to treat conditions that cause atrial fibrillation and flutter. Avoid binge drinking.

References

Calkins H, Tomaselli GF, Morady F. Atrial fibrillation: clinical features, mechanisms, and management. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 66.

Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(1):e1–e156. PMID: 38033089 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38033089/.

Zimetbaum P, Goldman L. Supraventricular ectopy and tachyarrhythmias. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 52.

Heart - section through the middle - illustration

The interior of the heart is composed of valves, chambers, and associated vessels.

Heart - section through the middle

illustration

Heart - front view - illustration

The external structures of the heart include the ventricles, atria, arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart while veins carry blood into the heart. The vessels colored blue indicate the transport of blood with relatively low content of oxygen and high content of carbon dioxide. The vessels colored red indicate the transport of blood with relatively high content of oxygen and low content of carbon dioxide.

Heart - front view

illustration

Anterior heart arteries - illustration

The coronary arteries supply blood to the heart muscle. The right coronary artery supplies both the left and the right heart; the left coronary artery supplies the left heart.

Anterior heart arteries

illustration

Conduction system of the heart - illustration

The intrinsic conduction system sets the basic rhythm of the beating heart by generating impulses which stimulate the heart to contract.

Conduction system of the heart

illustration

Heart - section through the middle - illustration

The interior of the heart is composed of valves, chambers, and associated vessels.

Heart - section through the middle

illustration

Heart - front view - illustration

The external structures of the heart include the ventricles, atria, arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart while veins carry blood into the heart. The vessels colored blue indicate the transport of blood with relatively low content of oxygen and high content of carbon dioxide. The vessels colored red indicate the transport of blood with relatively high content of oxygen and low content of carbon dioxide.

Heart - front view

illustration

Anterior heart arteries - illustration

The coronary arteries supply blood to the heart muscle. The right coronary artery supplies both the left and the right heart; the left coronary artery supplies the left heart.

Anterior heart arteries

illustration

Conduction system of the heart - illustration

The intrinsic conduction system sets the basic rhythm of the beating heart by generating impulses which stimulate the heart to contract.

Conduction system of the heart

illustration

Review Date: 1/1/2025

Reviewed By: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.