Pulmonary tuberculosis

TB; Tuberculosis - pulmonary; Mycobacterium - pulmonaryPulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious bacterial infection that involves the lungs. It may spread to other organs.

Causes

Pulmonary TB is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M tuberculosis). TB is contagious. This means the bacteria may spread from an infected person to someone else. You can get TB by breathing in air droplets from a cough or sneeze of an infected person. The resulting lung infection is called primary TB.

Most people recover from a primary TB infection without further evidence of the disease. The infection may stay inactive (dormant) for years. In some people, it becomes active again (reactivates).

Most people who develop symptoms of a TB infection first became infected in the past. In some cases, the disease becomes active within weeks after the primary infection.

The following people are at higher risk of active TB or reactivation of TB:

- Older adults

- Infants

- People with weakened immune systems, for example due to HIV/AIDS, chemotherapy, diabetes, or medicines that weaken the immune system

HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). When a person becomes infected with HIV, the ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleChemotherapy

The term chemotherapy is used to describe cancer-killing drugs. Chemotherapy may be used to:Cure the cancerShrink the cancerPrevent the cancer from ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleDiabetes

Diabetes is a long-term (chronic) disease in which the body cannot regulate the amount of sugar in the blood.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Your risk for catching TB increases if you:

- Are around people who have TB

- Live in crowded or unclean living conditions

- Have poor nutrition

The following factors can increase the rate of TB infection in a population:

- Increase in HIV infections

- Increase in number of homeless people (poor environment and nutrition)

- Presence of drug-resistant strains of TB

Symptoms

The primary stage of TB does not cause symptoms. When symptoms of pulmonary TB occur, they can include:

- Breathing difficulty

Breathing difficulty

Breathing difficulty may involve:Difficult breathing Uncomfortable breathingFeeling like you are not getting enough air

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Chest pain

- Cough (usually with mucus)

- Coughing up blood

- Excessive sweating, particularly at night

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Wheezing

Wheezing

Wheezing is a high-pitched whistling sound during breathing. It occurs when air moves through narrowed breathing tubes in the lungs.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. This may show:

- Clubbing of the fingers or toes (in people with advanced disease)

Clubbing of the fingers or toes

Clubbing is changes in the areas under and around the toenails and fingernails that occur with some disorders. The nails may also show changes....

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Swollen or tender lymph nodes in the neck or other areas

- Fluid around a lung (pleural effusion)

Pleural effusion

A pleural effusion is a buildup of fluid between the layers of tissue that line the lungs and chest cavity.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Unusual breath sounds in the lungs (crackles)

Tests that may be ordered include:

- Bronchoscopy (test that uses a scope to view the airways and collect samples from them)

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy is a test to view the airways and diagnose lung disease. It may also be used during the treatment of some lung conditions.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Chest CT scan

Chest CT scan

A chest CT (computed tomography) scan is an imaging method that uses x-rays to create cross-sectional pictures of the chest and upper abdomen....

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Chest x-ray

Chest x-ray

A chest x-ray is an x-ray of the chest, lungs, heart, large arteries, ribs, and diaphragm.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Interferon-gamma release blood test, such as the QFT-Gold test to test for TB infection (active or infection in the past)

- Sputum examination and cultures

Cultures

Routine sputum culture is a laboratory test that looks for germs that cause infection. Sputum is the material that comes up from air passages when y...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Thoracentesis (procedure to remove fluid from the space between the lining of the outside of the lungs and the wall of the chest)

Thoracentesis

Thoracentesis is a procedure to remove fluid from the space between the lining of the outside of the lungs (pleura) and the wall of the chest....

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Tuberculin skin test (also called a PPD test)

Tuberculin skin test

The PPD skin test is a method used to diagnose silent (latent) tuberculosis (TB) infection. PPD stands for purified protein derivative.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Biopsy of the affected tissue (rarely required)

Biopsy

A biopsy is the removal of a small piece of tissue for lab examination.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to cure the infection with medicines that fight TB bacteria. Active pulmonary TB is treated with a combination of many medicines (usually 4 medicines). The person takes the medicines until lab tests show which medicines work best.

You may need to take many different pills at different times of the day for 6 months or longer. It is very important that you take the pills the way your provider instructed.

When people do not take their TB medicines like they are supposed to, the infection can become much more difficult to treat. The TB bacteria can become resistant to treatment. This means the medicines no longer work.

If a person is not taking all the medicines as directed, a nurse or public health worker may need to watch the person take the prescribed medicines. This approach is called directly observed therapy. In this case, medicines may be given 2 or 3 times a week.

You may need to stay at home or be admitted to a hospital for 2 to 4 weeks to avoid spreading the disease to others until you are no longer contagious.

Your provider is required by law to report your TB illness to the local health department. Your health care team will ensure that you receive the best care.

Support Groups

You can ease the stress of illness by joining a support group. Sharing with others who have common experiences and problems can help you feel more in control.

Support group

The following organizations are good resources for information on lung disease:American Lung Association -- www. lung. orgNational Heart, Lung, and B...

Outlook (Prognosis)

Symptoms often improve in 2 to 3 weeks after starting treatment. A chest x-ray will not show this improvement until weeks or months later. The outlook is excellent if pulmonary TB is diagnosed early and effective treatment is started quickly.

Possible Complications

Pulmonary TB can cause permanent lung damage if not treated early. It can also spread to other parts of the body.

Medicines used to treat TB may cause side effects, including:

- Changes in vision

- Orange- or brown-colored tears and urine

- Rash

- Liver inflammation

Liver inflammation

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is an injury of the liver that may occur when you take certain medicines. Other types of liver injury include:Viral ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

A vision test may be done before the start of treatment so your provider can monitor any changes in the health of your eyes.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if:

- You think or know you have been exposed to TB

- You develop symptoms of TB

- Your symptoms continue despite treatment

- New symptoms develop

Prevention

TB is preventable, even in those who have been exposed to an infected person. Skin testing for TB is used in high-risk populations or in people who may have been exposed to TB, such as health care workers.

People who have been exposed to TB should have a skin test as soon as possible and have a follow-up test at a later date, if the first test is negative.

A positive skin test means you have come into contact with the TB bacteria. It does not mean that you have active TB or are contagious. Talk to your provider about how to prevent developing active TB.

Prompt treatment is very important in preventing the spread of TB from those who have active TB to those who have never been infected with TB.

Some countries with a high incidence of TB give people a vaccine called BCG to prevent TB. But, the effectiveness of this vaccine is limited and it is not used in the United States for the prevention of TB.

People who have had BCG may still be skin-tested for TB. Discuss the test results (if positive) with your provider.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Tuberculosis (TB). www.cdc.gov/tb/index.html. Updated January 17, 2025. Accessed March 13, 2025.

Fitzgerald DW, Sterling TR, Haas DW. Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 249.

Tuberculosis in the kidney - illustration

Kidneys can be damaged by tuberculosis. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but may cause infection in many other organs in the body. (Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Tuberculosis in the kidney

illustration

Tuberculosis in the lung - illustration

Tuberculosis is caused by a group of organisms, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M bovis, M africanum and a few other rarer subtypes. Tuberculosis usually appears as a lung (pulmonary) infection. However, it may infect other organs in the body. Recently, antibiotic-resistant strains of tuberculosis have appeared. With increasing numbers of immunocompromised individuals with AIDS, and homeless people without medical care, tuberculosis is seen more frequently today. (Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Tuberculosis in the lung

illustration

Tuberculosis, advanced - chest X-rays - illustration

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that causes inflammation, the formation of tubercles and other growths within tissue, and can cause tissue death. These chest x-rays show advanced pulmonary tuberculosis. There are multiple light areas (opacities) of varying size that run together (coalesce). Arrows indicate the location of cavities within these light areas. The x-ray on the left clearly shows that the opacities are located in the upper area of the lungs toward the back. The appearance is typical for chronic pulmonary tuberculosis but may also occur with chronic pulmonary histiocytosis and chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Pulmonary tuberculosis is making a comeback with new resistant strains that are difficult to treat. Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form of the disease, but other organs can be infected.

Tuberculosis, advanced - chest X-rays

illustration

Pulmonary nodule - front view chest x-ray - illustration

This x-ray shows a single lesion (pulmonary nodule) in the upper right lung (seen as a light area on the left side of the picture). The nodule has distinct borders (well-defined) and is uniform in density. Tuberculosis (TB) and other diseases can cause this type of lesion.

Pulmonary nodule - front view chest x-ray

illustration

Pulmonary nodule, solitary - CT scan - illustration

This CT scan shows a single lesion (pulmonary nodule) in the right lung. This nodule is seen as the light circle in the upper portion of the dark area on the left side of the picture. A normal lung would look completely black in a CT scan.

Pulmonary nodule, solitary - CT scan

illustration

Miliary tuberculosis - illustration

Miliary tuberculosis is characterized by a chronic, contagious bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that has spread to other organs of the body by the blood or lymph system.

Miliary tuberculosis

illustration

Tuberculosis of the lungs - illustration

Tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial disease that primarily involves the lungs. Tuberculosis may develop after inhaling infected droplets sprayed into the air from a cough or sneeze of someone infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis of the lungs

illustration

Erythema nodosum associated with sarcoidosis - illustration

This picture shows reddish-purple, hard (indurated), painful nodules (erythema nodosum) that occur most commonly on the shins. These lesions may be anywhere on the body and may be associated with tuberculosis (TB), sarcoidosis, coccidioidomycosis, systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE), fungal infections, or in response to medications.

Erythema nodosum associated with sarcoidosis

illustration

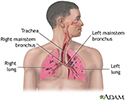

Respiratory system - illustration

Air is breathed in through the nasal passageways, travels through the trachea and bronchi to the lungs.

Respiratory system

illustration

Tuberculin skin test - illustration

The tuberculin skin test is performed to evaluate whether a person has been exposed to tuberculosis. If there has been a prior exposure, antibodies are formed and remain in the body. During the skin test, the tuberculosis antigen is injected under the skin and if antibodies are present, the body will have an immune response. There will be an area of inflammation at the site of the injection.

Tuberculin skin test

illustration

Tuberculosis in the kidney - illustration

Kidneys can be damaged by tuberculosis. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but may cause infection in many other organs in the body. (Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Tuberculosis in the kidney

illustration

Tuberculosis in the lung - illustration

Tuberculosis is caused by a group of organisms, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M bovis, M africanum and a few other rarer subtypes. Tuberculosis usually appears as a lung (pulmonary) infection. However, it may infect other organs in the body. Recently, antibiotic-resistant strains of tuberculosis have appeared. With increasing numbers of immunocompromised individuals with AIDS, and homeless people without medical care, tuberculosis is seen more frequently today. (Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Tuberculosis in the lung

illustration

Tuberculosis, advanced - chest X-rays - illustration

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that causes inflammation, the formation of tubercles and other growths within tissue, and can cause tissue death. These chest x-rays show advanced pulmonary tuberculosis. There are multiple light areas (opacities) of varying size that run together (coalesce). Arrows indicate the location of cavities within these light areas. The x-ray on the left clearly shows that the opacities are located in the upper area of the lungs toward the back. The appearance is typical for chronic pulmonary tuberculosis but may also occur with chronic pulmonary histiocytosis and chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Pulmonary tuberculosis is making a comeback with new resistant strains that are difficult to treat. Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form of the disease, but other organs can be infected.

Tuberculosis, advanced - chest X-rays

illustration

Pulmonary nodule - front view chest x-ray - illustration

This x-ray shows a single lesion (pulmonary nodule) in the upper right lung (seen as a light area on the left side of the picture). The nodule has distinct borders (well-defined) and is uniform in density. Tuberculosis (TB) and other diseases can cause this type of lesion.

Pulmonary nodule - front view chest x-ray

illustration

Pulmonary nodule, solitary - CT scan - illustration

This CT scan shows a single lesion (pulmonary nodule) in the right lung. This nodule is seen as the light circle in the upper portion of the dark area on the left side of the picture. A normal lung would look completely black in a CT scan.

Pulmonary nodule, solitary - CT scan

illustration

Miliary tuberculosis - illustration

Miliary tuberculosis is characterized by a chronic, contagious bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that has spread to other organs of the body by the blood or lymph system.

Miliary tuberculosis

illustration

Tuberculosis of the lungs - illustration

Tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial disease that primarily involves the lungs. Tuberculosis may develop after inhaling infected droplets sprayed into the air from a cough or sneeze of someone infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis of the lungs

illustration

Erythema nodosum associated with sarcoidosis - illustration

This picture shows reddish-purple, hard (indurated), painful nodules (erythema nodosum) that occur most commonly on the shins. These lesions may be anywhere on the body and may be associated with tuberculosis (TB), sarcoidosis, coccidioidomycosis, systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE), fungal infections, or in response to medications.

Erythema nodosum associated with sarcoidosis

illustration

Respiratory system - illustration

Air is breathed in through the nasal passageways, travels through the trachea and bronchi to the lungs.

Respiratory system

illustration

Tuberculin skin test - illustration

The tuberculin skin test is performed to evaluate whether a person has been exposed to tuberculosis. If there has been a prior exposure, antibodies are formed and remain in the body. During the skin test, the tuberculosis antigen is injected under the skin and if antibodies are present, the body will have an immune response. There will be an area of inflammation at the site of the injection.

Tuberculin skin test

illustration

Review Date: 11/10/2024

Reviewed By: Jatin M. Vyas, MD, PhD, Professor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Associate in Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.