How wounds heal

How cuts heal; How scrapes heal; How puncture wounds heal; How burns heal; How pressure sores heal; How lacerations healA wound is a break or opening in the skin. Your skin protects your body from germs. When the skin is broken, even during surgery, germs can enter and cause infection. Wounds often occur because of an accident or injury.

Types of wounds include:

- Cuts

- Scrapes

- Puncture wounds

- Burns

Burns

Burns commonly occur by direct or indirect contact with heat, electric current, radiation, or chemical agents. Burns can lead to cell death, which c...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Pressure sores

A wound may be smooth or jagged. It may be near the surface of the skin or deeper. Deep wounds can affect:

- Tendons

- Muscles

- Ligaments

- Nerves

- Blood vessels

- Bones

Minor wounds often heal easily, but all wounds need care to prevent infection.

Stages of Wound Healing

Wounds heal in stages. The smaller the wound, the quicker it will heal. The larger or deeper the wound, the longer it takes to heal. When you get a cut, scrape, or puncture, the wound will bleed.

- The blood will start to clot within a few minutes or less and stop the bleeding.

- The blood clots dry and form a scab, which protects the tissue underneath from germs.

Not all wounds bleed. For example, burns, some puncture wounds, and pressure sores do not bleed.

Once the scab forms, your body's immune system starts to protect the wound from infection.

- The wound becomes slightly swollen, red or pink, and tender.

- You also may see some clear fluid oozing from the wound. This fluid helps clean the area.

- Blood vessels open in the area, so blood can bring oxygen and nutrients to the wound. Oxygen is essential for healing.

- White blood cells help fight infection from germs and begin to repair the wound.

- This stage takes about 2 to 5 days.

Tissue growth and rebuilding occur next.

- Over the next 3 weeks or so, the body repairs broken blood vessels and new tissue grows.

- Red blood cells help create collagen, which are tough, white fibers that form the foundation for new tissue.

- The wound starts to fill in with new tissue, called granulation tissue.

- New skin begins to form over this tissue.

- As the wound heals, the edges pull inward and the wound gets smaller.

A scar forms and the wound becomes stronger.

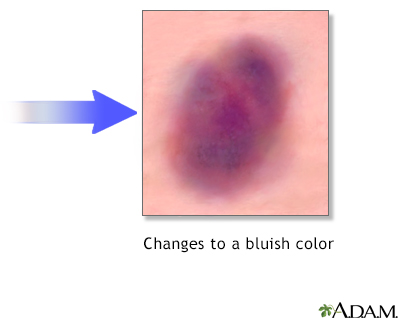

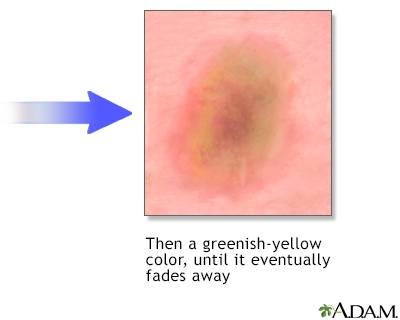

- As healing continues, you may notice that the area itches. After the scab falls off, the area may look stretched, red, and shiny.

- The scar that forms will be smaller than the original wound. It will be less strong and less flexible than the surrounding skin.

- Over time, the scar will fade and may disappear completely. This can take as long as 2 years. Some scars never go away completely.

- Scars form because the new tissue grows back differently than the original tissue. If you only injured the top layer of skin, you will probably not have a scar. With deeper wounds, you are more likely to have a scar.

Some people are more likely to scar than others. Some may have thick, unsightly scars called keloids. People with darker complexions are more likely to have keloids form.

Keloids

A keloid is a growth of extra scar tissue. It occurs where the skin has healed after an injury.

Taking Care of Your Wound

Properly caring for your wound means keeping it clean and covered. This can help prevent infections and scarring.

- For minor wounds, clean your wound with gentle soap and water. Cover the wound with a sterile bandage or other dressing.

- For major wounds, follow your health care provider's instructions on how to care for your injury.

- Avoid picking at or scratching the scab. This can interfere with healing and cause scarring.

- Once the scar forms, some people think it helps to massage it with vitamin E or petroleum jelly. However, this is not proven to help prevent a scar or help it fade. Do not rub your scar or apply anything to it without talking with your provider first.

Outlook

When cared for properly, most wounds heal well, leaving only a small scar or none at all. With larger wounds, you are more likely to have a scar.

Certain factors can prevent wounds from healing or slow the process, such as:

- Infection can make a wound larger and take longer to heal.

- Diabetes. People with diabetes are more likely to have wounds that won't heal, which are also called long-term (chronic) wounds.

Diabetes

Diabetes is a long-term (chronic) disease in which the body cannot regulate the amount of sugar in the blood.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleChronic

Chronic refers to something that continues over an extended period of time. A chronic condition is usually long-lasting and does not easily or quick...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Poor blood flow due to clogged arteries (arteriosclerosis) or conditions such as varicose veins.

Arteriosclerosis

Atherosclerosis, sometimes called "hardening of the arteries," occurs when fat, cholesterol, and other substances build up in the walls of arteries. ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleVaricose veins

Varicose veins are swollen, twisted, and enlarged veins that you can see under the skin. They are often red or blue in color. They most often appea...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Obesity increases the risk of infection after surgery. Being overweight can also put tension on stitches, which can make them break open.

- Age. In general, older adults heal more slowly than younger people.

- Heavy alcohol use can slow healing and increase the risk for infection and complications after surgery.

- Stress may cause you to not get enough sleep, eat poorly, and smoke or drink more, which can interfere with healing.

- Medicines such as corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and some chemotherapy medicines can slow healing.

- Smoking can delay healing after surgery. It also increases the risk for complications such as infection and wounds breaking open.

Wounds that are slow to heal may need extra care from your provider.

When to Call the Doctor

Contact your provider right away if you have:

- Redness, increased pain, or yellow or green pus, or excessive clear fluid around the injury. These are signs of infection.

- Black edges around the injury. This is a sign of dead tissue.

- Bleeding at the injury site that will not stop after 10 minutes of direct pressure.

- Fever of 100°F (37.7°C) or higher for more than 4 hours.

- Pain at the wound that will not go away, even after taking pain medicine.

- A wound that has come open or the stitches or staples have come out too soon.

References

Boukovalas S, Aliano KA, Phillips LG, Norbury WB. Wound healing. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:chap 6.

Woelfel SL, Armstrong DG, Shin L. Wound care. In: Sidawy AN, Perler BA, eds. Rutherford's Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 118.

Review Date: 5/29/2024

Reviewed By: Debra G. Wechter, MD, FACS, General Surgery Practice Specializing in Breast Cancer, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.