Muscle function loss

Paralysis; Paresis; Loss of movement; Motor dysfunctionMuscle function loss is when a muscle does not work or move normally. The medical term for complete loss of muscle function is paralysis.

Considerations

Loss of muscle function may be caused by:

- A disease of the muscle itself (myopathy)

- A disease of the area where the muscle and nerve meet (neuromuscular junction)

- A disease of the nervous system: Nerve damage (neuropathy), spinal cord injury (myelopathy), or brain damage (stroke or other brain injury)

Stroke

A stroke occurs when blood flow to a part of the brain stops. A stroke is sometimes called a "brain attack. " If blood flow is cut off for longer th...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

The loss of muscle function after some of these types of events can be severe. In some cases, muscle strength may not completely return, even with treatment.

Paralysis can be temporary or permanent. It can affect a small area (localized or focal) or be widespread (generalized). It may affect one side (unilateral) or both sides (bilateral).

If the paralysis affects the lower half of the body and both legs it is called paraplegia. If it affects both arms and legs, it is called quadriplegia. If the paralysis affects the muscles that cause breathing, it is quickly life threatening.

Causes

Diseases of the muscles that cause muscle-function loss include:

- Alcohol-associated myopathy

- Congenital myopathies (most often due to a genetic disorder)

-

Dermatomyositis and polymyositis

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is a disease that involves muscle inflammation and a skin rash. Polymyositis is a similar inflammatory condition that also involves ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticlePolymyositis

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis are rare inflammatory diseases. (The condition is called dermatomyositis when it involves the skin. ) These disease...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Drug-induced myopathy (statins, steroids)

-

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of inherited disorders that cause muscle weakness and loss of muscle tissue, which get worse over time.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Diseases of the nervous system that cause muscle function loss include:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig disease)

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, is a disease of the nerve cells in the brain, brain stem and spinal cord that control voluntary muscle movemen...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Bell palsy

Bell palsy

Bell palsy is a disorder of the nerve that controls movement of the muscles in the face. This nerve is called the facial or seventh cranial nerve. D...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Botulism

Botulism

Botulism is a rare but serious illness caused by Clostridium botulinum bacteria. The bacteria may enter the body through wounds or by eating imprope...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a serious health problem that occurs when the body's defense (immune) system mistakenly attacks part of the peripher...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Myasthenia gravis or Lambert-Eaton Syndrome

Myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia gravis is a neuromuscular disorder. Neuromuscular disorders involve the muscles and the nerves that control them.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Neuropathy

- Paralytic shellfish poisoning

Shellfish

This article describes a group of different conditions caused by eating contaminated fish and seafood. The most common of these are ciguatera poison...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Periodic paralysis

- Focal nerve injury

-

Polio or other viruses

Polio

Polio is a viral disease that can affect nerves and can lead to partial or full paralysis. The medical name for polio is poliomyelitis.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Spinal cord or brain injury

Spinal cord or brain injury

Spinal cord trauma is damage to the spinal cord. It may result from direct injury to the cord itself or indirectly from disease of the nearby bones,...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Stroke

Home Care

Sudden loss of muscle function is a medical emergency. Get medical help right away.

After you have received medical treatment, your health care provider may recommend some of the following measures:

- Follow your prescribed therapy.

- If the nerves to your face or head are damaged, you may have difficulty chewing and swallowing or closing your eyes. In these cases, a soft diet may be recommended. You will also need some form of eye protection, such as a patch over the eye while you are asleep.

- Long-term immobility can cause serious complications. Change positions often and take care of your skin. Range-of-motion exercises may help to maintain some muscle tone.

-

Splints may help prevent muscle contractures, a condition in which a muscle becomes permanently shortened.

Splints

A splint is a device used to hold a part of the body stable to decrease pain and prevent further injury.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Muscle paralysis always requires immediate medical attention. If you notice gradual weakening or problems with a muscle, get medical attention as soon as possible.

What to Expect at Your Office Visit

The provider will perform a physical exam and ask questions about your medical history and symptoms, including:

Physical exam

During a physical examination, a health care provider checks your body to determine if you do or do not have a physical problem. A physical examinati...

Location:

- What part(s) of your body are affected?

- Does it affect one or both sides of your body?

- Did it develop in a top-to-bottom pattern (descending paralysis), or a bottom-to-top pattern (ascending paralysis)?

- Do you have difficulty getting out of a chair or climbing stairs?

- Do you have difficulty lifting your arm above your head?

- Do you have problems extending or lifting your wrist (wrist drop)?

- Do you have difficulty gripping (grasping)?

Symptoms:

- Do you have pain?

- Do you have numbness, tingling, or loss of sensation?

Numbness

Numbness and tingling are abnormal sensations that can occur anywhere in your body, but they are often felt in your fingers, hands, feet, arms, or le...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleTingling

Numbness and tingling are abnormal sensations that can occur anywhere in your body, but they are often felt in your fingers, hands, feet, arms, or le...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleLoss of sensation

Numbness and tingling are abnormal sensations that can occur anywhere in your body, but they are often felt in your fingers, hands, feet, arms, or le...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Do you have difficulty controlling your bladder or bowels?

- Do you have shortness of breath?

- What other symptoms do you have?

Time pattern:

- Do episodes occur repeatedly (recurrent)?

- How long do they last?

- Is the muscle function loss getting worse (progressive)?

- Is it progressing slowly or quickly?

- Does it become worse over the course of the day?

Aggravating and relieving factors:

- What, if anything, makes the paralysis worse?

- Does it get worse after you take potassium supplements or other medicines?

- Is it better after you rest?

Tests that may be performed include:

- Blood tests (such as CBC, white blood cell differential, blood chemistry levels, and muscle enzyme levels)

CBC

A complete blood count (CBC) test measures the following:The number of white blood cells (WBC count)The number of red blood cells (RBC count)The numb...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark ArticleWhite blood cell differential

The blood differential test measures the percentage of each type of white blood cell (WBC) that you have in your blood. It also reveals if there are...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

CT scan of the head or spine

CT scan of the head

A head computed tomography (CT) scan uses many x-rays to create pictures of the head, including the skull, brain, eye sockets, and sinuses.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

MRI of the head or spine

MRI of the head

A head MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is an imaging test that uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create pictures of the brain and surrounding...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Lumbar puncture (spinal tap)

- Muscle or nerve biopsy

Biopsy

A biopsy is the removal of a small piece of tissue for lab examination.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Myelography

- Muscle ultrasound

- Nerve conduction studies and electromyography

Electromyography

Electromyography (EMG) is a test that checks the health of the muscles and the nerves that control the muscles.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Intravenous feeding or feeding tubes may be required in severe cases. Physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech therapy may be recommended.

Intravenous

Intravenous means "within a vein. " Most often it refers to giving medicines or fluids through a needle or tube inserted into a vein. This allows th...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleReferences

Kaminski HJ. Disorders of neuromuscular transmission. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 390.

Selcen D. Muscle diseases. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 389.

Warner WC, Sawyer JR. Neuromuscular disorders. In: Azar FM, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 35.

-

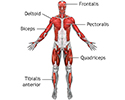

Superficial anterior muscles - illustration

Superficial muscles are close to the surface of the skin. Muscles which lie closer to bone or internal organs are called deep muscles.

Superficial anterior muscles

illustration

-

Deep anterior muscles - illustration

Muscle tissue is composed primarily of contractile cells. Contractile cells have the ability to produce movement.

Deep anterior muscles

illustration

-

Tendons and muscles - illustration

Tendons connect muscles to their bony origins and insertions.

Tendons and muscles

illustration

-

Lower leg muscles - illustration

The muscular components of the lower leg include the gastrocnemius, soleus, peroneus longus, tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and the Achilles tendon.

Lower leg muscles

illustration

-

Superficial anterior muscles - illustration

Superficial muscles are close to the surface of the skin. Muscles which lie closer to bone or internal organs are called deep muscles.

Superficial anterior muscles

illustration

-

Deep anterior muscles - illustration

Muscle tissue is composed primarily of contractile cells. Contractile cells have the ability to produce movement.

Deep anterior muscles

illustration

-

Tendons and muscles - illustration

Tendons connect muscles to their bony origins and insertions.

Tendons and muscles

illustration

-

Lower leg muscles - illustration

The muscular components of the lower leg include the gastrocnemius, soleus, peroneus longus, tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and the Achilles tendon.

Lower leg muscles

illustration

-

Weight control and diet - InDepth

(In-Depth)

Review Date: 3/31/2024

Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.