Large bowel resection

Ascending colectomy; Descending colectomy; Transverse colectomy; Right hemicolectomy; Left hemicolectomy; Low anterior resection; Sigmoid colectomy; Subtotal colectomy; Proctocolectomy; Colon resection; Laparoscopic colectomy; Colectomy - partial; Abdominal perineal resectionLarge bowel resection is surgery to remove all or part of your large bowel. This surgery is also called colectomy. The large bowel is also called the large intestine or colon.

- Removal of the entire colon and the rectum is called a proctocolectomy.

- Removal of all of the colon but not the rectum is called subtotal colectomy.

- Removal of part of the colon but not the rectum is called a partial colectomy.

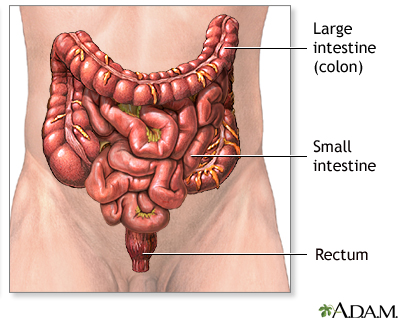

The large bowel connects the small intestine to the anus. Normally, stool passes through the large bowel before leaving the body through the anus.

Description

You'll receive general anesthesia at the time of your surgery. This will keep you asleep and pain-free.

General anesthesia

General anesthesia is treatment with certain medicines that puts you into a deep sleep-like state so you do not feel pain during surgery. After you ...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleThe surgery can be performed laparoscopically or with open surgery. Depending on which surgery you have, the surgeon will make one or more cuts (incisions) in your belly.

If you have laparoscopic surgery:

- The surgeon makes 3 to 5 small cuts (incisions) in your belly. A medical device called a laparoscope is inserted through one of the cuts. The scope is a thin, lighted tube with a camera on the end. It lets the surgeon see inside your belly. Other medical instruments are inserted through the other cuts.

- A cut of about 2 to 3 inches (5 to 7.6 centimeters) may also be made if your surgeon needs to put their hand inside your belly to feel or remove the diseased bowel.

- Your belly is filled with a harmless gas to expand it. This makes the area easier for the surgeon to see and work in.

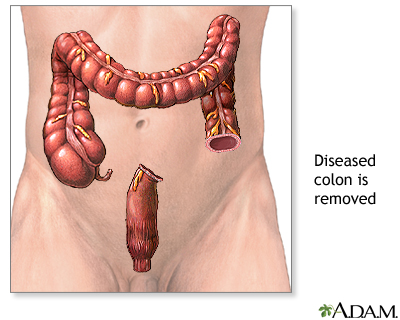

- The surgeon examines the organs in your belly to see if there are any problems.

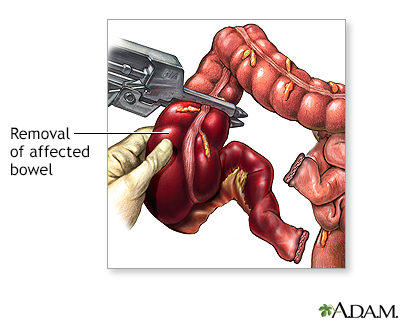

- The diseased part of your large bowel is located and removed. Some lymph nodes may also be removed.

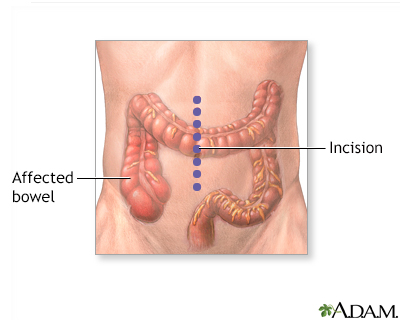

If you have open surgery:

- The surgeon makes a cut of 6 to 8 inches (15.2 to 20.3 centimeters) in your lower belly.

- The organs in your belly are examined to see if there are any problems.

- The diseased part of your large bowel is located and removed. Some lymph nodes may also be removed.

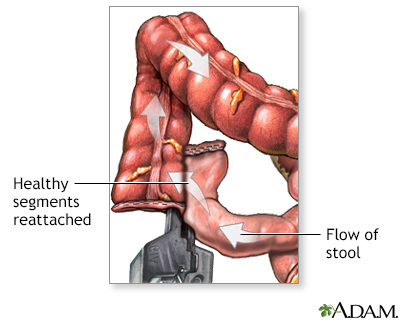

In both kinds of surgery, the next steps are:

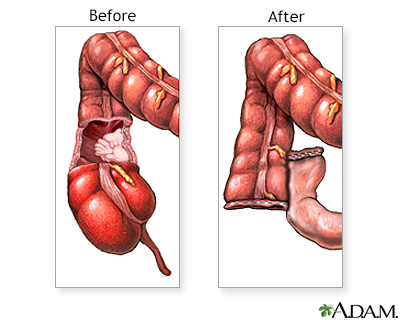

- If there is enough healthy large intestine left, the ends are stitched or stapled together. This is called an anastomosis. Most patients have this done.

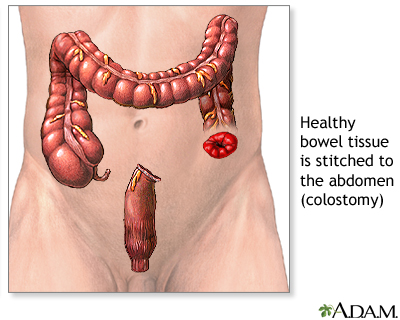

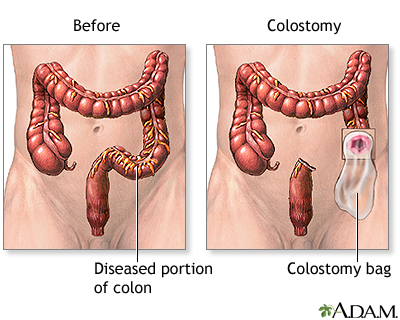

- If there is not enough healthy large intestine to reconnect, the surgeon makes an opening called a stoma through the skin of your belly. The colon is attached to the outer wall of your belly. Stool will go through the stoma into a drainage bag outside your body. This is called a colostomy. The colostomy may be either short-term or permanent.

Colostomy

Colostomy is a surgical procedure that brings one end of the large intestine out through an opening (stoma) made in the abdominal wall. Stools movin...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Colectomy usually takes between 1 and 4 hours.

Why the Procedure Is Performed

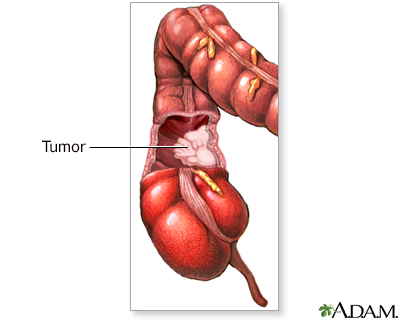

Large bowel resection is used to treat many conditions, including:

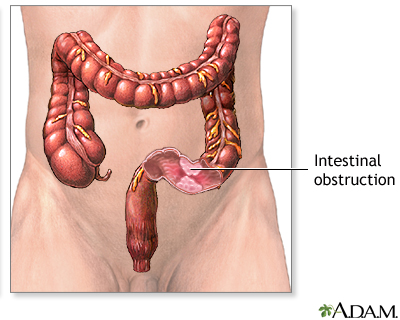

- A blockage in the intestine due to scar tissue

A blockage in the intestine

Intestinal obstruction is a partial or complete blockage of the bowel. The contents of the intestine cannot pass through it.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Colon cancer

Colon cancer

Colorectal cancer is cancer that starts in the large intestine (colon) or the rectum (end of the colon). It is also sometimes simply called colon ca...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Diverticular disease (disease of the large bowel)

Diverticular disease

Diverticula are small, bulging sacs or pouches that form on the inner wall of the intestine. Diverticulitis occurs when these pouches become inflame...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Other reasons for bowel resection are:

- Familial polyposis (polyps are growths on the lining of the colon or rectum)

Familial polyposis

A colorectal polyp is a growth on the lining of the colon or rectum.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Injuries that damage the large bowel

- Intussusception (when one part of the intestine pushes into another)

- Precancerous polyps

- Severe gastrointestinal bleeding

- Twisting of the bowel (volvulus)

- Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a condition in which the lining of the large intestine (colon) and rectum become inflamed. It is a form of inflammatory bowel ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Bleeding from the large intestine

- Lack of nerve function to the large intestine

Risks

Risks for anesthesia and surgery in general are:

- Reactions to medicines

- Breathing problems

- Blood clots, bleeding, infection

Risks for this surgery are:

- Bleeding inside your belly

- Bulging tissue through the surgical cut, called an incisional hernia

Hernia

A groin lump is swelling in the groin area. This is where the upper leg meets the lower abdomen.

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Damage to nearby organs in the body

- Damage to the ureter or bladder

- Problems with the colostomy

- Scar tissue that forms in the belly and causes a blockage of the intestines

- The edges of your intestines that are sewn together come open (anastomotic leak, which may be life threatening)

- Wound breaking open

- Wound infection

- Peritonitis

Before the Procedure

Tell your surgeon or nurse what medicines you are taking, even medicines, supplements, or herbs you bought without a prescription.

Talk with your surgeon or nurse about how surgery will affect:

- Intimacy and sexuality

- Pregnancy

- Sports

- Work

During the 2 weeks before your surgery:

- You may be asked to stop taking blood thinning medicines. These include aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), and others.

- Ask the surgeon which medicines you should still take on the day of your surgery.

- If you smoke, try to stop. Smoking increases the risk for problems such as slow healing. Ask your health care provider or nurse for help quitting.

- Tell the surgeon right away if you have a cold, flu, fever, herpes breakout, or other illness before your surgery.

- You may be asked to go through a bowel preparation to clean your intestines of all stool. This may involve staying on a liquid diet for a few days and using laxatives.

The day before surgery:

- You may be asked to drink only clear liquids such as broth, clear juice, and water.

- Follow instructions about when to stop eating and drinking.

On the day of surgery:

- Take the medicines your surgeon told you to take with a small sip of water.

- Arrive at the hospital on time.

After the Procedure

You will be in the hospital for 3 to 7 days. You may have to stay longer if the colectomy was an emergency operation.

You may also need to stay longer if a large amount of your large intestine was removed or if you develop problems.

By the second or third day, you will probably be able to drink clear liquids. Thicker fluids and then soft foods will be added as your bowel begins to work again.

After you go home, follow instructions on how to take care of yourself as you heal.

Follow instructions

You had surgery to remove all or part of your large intestine (large bowel). You may also have had a colostomy. This article describes what to expe...

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleOutlook (Prognosis)

Most people who have a large bowel resection recover fully. Even with a colostomy, most people are able to do the activities they were doing before their surgery. This includes most sports, travel, gardening, hiking, other outdoor activities, and most types of work.

If you have a long-term (chronic) condition, such as cancer, Crohn disease, or ulcerative colitis, you may need ongoing medical treatment.

References

Cameron J. Large bowel. In: Cameron J, ed. Current Surgical Therapy. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:177-286.

Galandiuk S, Netz U, Morpurgo E, Tosato SM, Abu-Freha N, Ellis CT. Colon and rectum. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 52.

The large intestine - illustration

The large intestine (or colon, or large bowel) is the last structure to process food, taking the undigestible matter from the small intestine, absorbing water from it and leaving the waste product called feces. Feces are expelled from the body through the rectum and the anus.

The large intestine

illustration

Colostomy - Series

Presentation

Large bowel resection - Series

Presentation

Blood supply of the large intestine - illustration

The blood supply to the large intestine originates in the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries.

Blood supply of the large intestine

illustration

The large intestine - illustration

The large intestine (or colon, or large bowel) is the last structure to process food, taking the undigestible matter from the small intestine, absorbing water from it and leaving the waste product called feces. Feces are expelled from the body through the rectum and the anus.

The large intestine

illustration

Colostomy - Series

Presentation

Large bowel resection - Series

Presentation

Blood supply of the large intestine - illustration

The blood supply to the large intestine originates in the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries.

Blood supply of the large intestine

illustration

Review Date: 3/11/2023

Reviewed By: Debra G. Wechter, MD, FACS, General Surgery Practice Specializing in Breast Cancer, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

![<strong>Large bowel resection - series</strong><p>The large bowel [large intestine or the colon] is part of the digestive system. It runs from the small intestine to the rectum. It is made up of three portions; the ascending, transverse and descending colon. The ascending colon is sometimes referred to as the right colon; the descending colon is sometimes referred to as the left, or sigmoid colon.</p> Large bowel resection - series](../../graphics/images/en/10255.jpg)