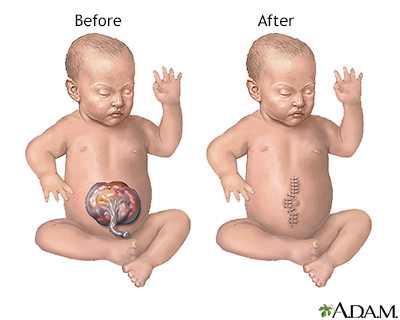

Omphalocele repair

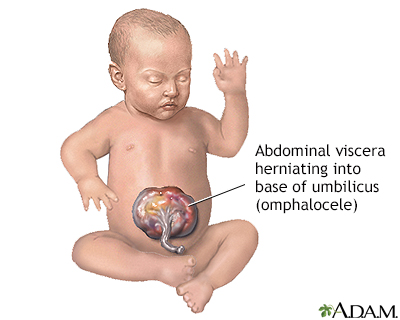

Omphalocele repair is a procedure done on an infant to correct a birth defect in the wall of the belly (abdomen) in which all or part of the bowel, possibly the liver and other organs stick out of the belly button (navel) in a thin sac.

Omphalocele

An omphalocele is a birth defect in which an infant's intestine or other abdominal organs are outside of the body because of a hole in the belly butt...

Other birth defects may also be present.

Description

The goal of the procedure is to place the organs back into the baby's belly and fix the defect. Repair may be done right after the baby is born. This is called a primary repair. Or, the repair is done in stages. This is called a staged repair.

Surgery for primary repair is most often done for a small omphalocele.

- Right after birth, the sac with the organs outside the belly is covered with a sterile dressing to protect it.

- When the doctors determine your newborn is strong enough for surgery, your baby is prepared for the operation.

- Your baby receives general anesthesia. This is medicine that allows your baby to sleep and be pain-free during the operation.

General anesthesia

General anesthesia is treatment with certain medicines that puts you into a deep sleep-like state so you do not feel pain during surgery. After you ...

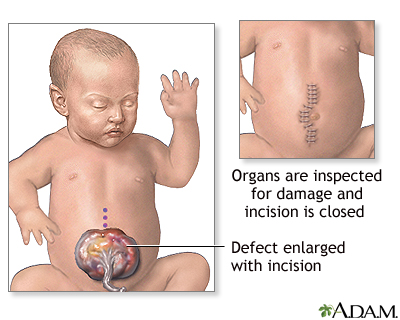

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - The surgeon makes a cut (incision) to remove the sac around the organs.

- The organs are examined closely for signs of damage or other birth defects. Unhealthy parts are removed. The healthy edges are stitched together.

- The organs are placed back into the belly.

- The opening in the wall of the belly is repaired.

Staged repair is done when your baby isn't stable enough for primary repair. Or, it is done if the omphalocele is very large and the organs can't fit into the baby's belly. The repair is performed the following way:

- Right after birth, a plastic pouch (called a silo) or a mesh-type of material is used to contain the omphalocele. The pouch or mesh is then attached to the baby's belly.

- Every 2 to 3 days, the doctor gently tightens the pouch or mesh to push the intestine into the belly.

- It may take up to 2 weeks or more for all of the organs to be back inside the belly. The pouch or mesh is then removed. The opening in the belly is repaired.

Why the Procedure Is Performed

Omphalocele is a life-threatening condition. It needs to be treated soon after birth so that the baby's organs can develop and be protected in the belly.

Risks

Risks for anesthesia and surgery in general are:

- Allergic reactions to medicines

- Breathing problems

- Bleeding

- Infection

Risks for omphalocele repair are:

- Breathing problems. The baby may need a breathing tube and breathing machine for a few days or weeks after surgery.

- Inflammation of the tissue that lines the wall of the abdomen and covers the abdominal organs.

- Organ injury.

- Problems with digestion and absorbing nutrients from food, if a baby has a lot of damage to the small bowel.

Before the Procedure

Omphalocele is usually seen on ultrasound before the baby is born. After it is found, your baby will be followed very closely to make sure they are growing.

Your baby should be delivered at a hospital that has a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and a pediatric surgeon. A NICU is set up to handle emergencies that occur at birth. A pediatric surgeon has special training in surgery for babies and children. Most babies who are known to have a giant omphalocele are delivered by cesarean section (C-section).

After the Procedure

After surgery, your baby will receive care in the NICU. Your baby will be placed in a special bed to keep them warm.

Your baby may need to be on a breathing machine until organ swelling has decreased and the size of the belly area has increased.

Other treatments your baby will probably need after surgery are:

- Antibiotics

- Fluids and nutrients given through a vein

- Oxygen

- Pain medicines

- A nasogastric (NG) tube placed through the nose into the stomach to drain the stomach and keep it empty

Feedings are started through the NG tube as soon as your baby's bowel starts working after surgery. Feedings by mouth will start very slowly. Your baby may eat slowly and may need feeding therapy, lots of encouragement, and time to recover after a feeding.

How long your baby stays in the hospital depends on whether there are other birth defects and complications. You may be able to take your baby home once they start taking all foods by mouth and gaining weight.

Outlook (Prognosis)

After you go home, your child may develop a blockage in the intestines (bowel obstruction) due to a kink or scar in the intestines. The doctor can tell you how this will be treated.

Bowel obstruction

Intestinal obstruction is a partial or complete blockage of the bowel. The contents of the intestine cannot pass through it.

Most of the time, surgery can correct omphalocele. How well your baby does depends on how much damage or loss of intestine there was, and whether your child has other birth defects.

Some babies have gastroesophageal reflux after surgery. This condition causes food or stomach acid to come back up from the stomach into the esophagus.

Gastroesophageal reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux occurs when stomach contents leak backward from the stomach into the esophagus. This causes "spitting up" in infants....

Some babies with large omphaloceles may also have small lungs and may need to use a breathing machine.

All babies born with an omphalocele should have chromosome testing. This will help parents understand the risk for this disorder in future pregnancies.

Reviewed By

Debra G. Wechter, MD, FACS, General Surgery Practice Specializing in Breast Cancer, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Chung DH. Pediatric surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:chap 67.

Ledbetter DJ, Chabra S, Javid PJ. Abdominal wall defects. In: Gleason CA, Juul SE, eds. Avery's Diseases of the Newborn. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 73.

Polites S, Nathan JD. Newborn abdominal wall defects. In: Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, eds. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 58.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.