Mitral valve regurgitation

Mitral valve regurgitation; Mitral valve insufficiency; Heart mitral regurgitation; Valvular mitral regurgitationMitral regurgitation is a disorder in which the mitral valve on the left side of the heart does not close properly.

Regurgitation means leaking from a valve that does not close all the way.

Causes

Blood that flows between different chambers of your heart must flow through a valve. The valve between the 2 chambers on the left side of your heart is called the mitral valve. It opens up enough so that blood can flow from the upper chamber of your heart (left atrium) to the lower chamber (left ventricle). It then closes, keeping blood from flowing backwards.

When the mitral valve doesn't close all the way, blood flows backward into the upper heart chamber (atrium) from the lower chamber as it contracts. This is called mitral regurgitation and is a common type of heart valve disorder. This cuts down on the amount of blood that flows to the rest of the body. As a result, the heart may try to pump harder. This may lead to congestive heart failure.

Mitral regurgitation may begin suddenly. This often occurs after a heart attack. When the regurgitation does not go away, it becomes long-term (chronic).

Many other diseases or problems can weaken or damage the valve or the heart tissue around the valve. You are at risk for mitral valve regurgitation if you have:

- Coronary heart disease and high blood pressure

- Infection of the heart valves

-

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP)

Mitral valve prolapse

Mitral valve prolapse is a heart problem involving the mitral valve, which separates the upper and lower chambers of the left side of the heart. In ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Rare conditions, such as untreated syphilis or Marfan syndrome

Marfan syndrome

Marfan syndrome is a disorder of connective tissue. This is the tissue that strengthens the body's structures. Disorders of connective tissue affect...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Rheumatic heart disease. This is a complication of untreated strep throat that is becoming less common.

- Swelling of the left lower heart chamber

Another important risk factor for mitral regurgitation is past use of a diet pill called "Fen-Phen" (fenfluramine and phentermine) or dexfenfluramine. The drug was removed from the market by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1997 because of safety concerns.

Symptoms

Symptoms may begin suddenly if:

- A heart attack damages the muscles around the mitral valve.

- The cords that attach the muscle to the valve break.

- An infection of the valve destroys part of the valve.

There are often no symptoms. When symptoms occur, they often develop gradually, and may include:

- Cough

-

Fatigue, exhaustion, and lightheadedness

Fatigue

Fatigue is a feeling of weariness, tiredness, or lack of energy.

Read Article Now Book Mark ArticleExhaustion

Fatigue is a feeling of weariness, tiredness, or lack of energy.

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Rapid breathing

- Sensation of feeling the heart beat (palpitations) or a rapid heartbeat

Palpitations

Palpitations are feelings or sensations that your heart is pounding or racing. They can be felt in your chest, throat, or neck. You may:Have an unpl...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Shortness of breath that increases with activity and when lying down

- Waking up an hour or so after falling asleep because of trouble breathing

-

Urination, excessive at night

Urination, excessive at night

Normally, the amount of urine your body produces decreases at night. This allows most people to sleep 6 to 8 hours without having to urinate. Some p...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Exams and Tests

When listening to your heart and lungs, the health care provider may detect:

- A thrill (vibration) over the heart when feeling the chest area

Feeling the chest area

Palpation is a method of feeling with the fingers or hands during a physical examination. The health care provider touches and feels your body to ex...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - An extra heart sound (S4 gallop)

- A distinctive heart murmur

- Crackles in the lungs (if fluid backs up into the lungs)

The physical exam may also reveal:

- Ankle and leg swelling

-

Enlarged liver

Enlarged liver

Enlarged liver refers to swelling of the liver beyond its normal size. Hepatomegaly is another word to describe this problem. If both the liver and ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Bulging neck veins

- Other signs of right-sided heart failure

The following tests may be done to look at the heart valve structure and function:

-

CT scan of the heart

CT scan of the heart

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the heart is an imaging method that uses x-rays to create detailed pictures of the heart and its blood vessels. Th...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Echocardiogram (an ultrasound examination of the heart) - transthoracic or transesophageal

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram is a test that uses sound waves to create pictures of the heart. The picture and information it produces is more detailed than a s...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging

Heart magnetic resonance imaging is an imaging method that uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create pictures of the heart. It does not use ra...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

Cardiac catheterization may be done if heart function becomes worse.

Treatment

Treatment will depend on what symptoms you have, what condition caused the mitral valve regurgitation, how well the heart is working, and if the heart has become enlarged.

People with high blood pressure or a weakened heart muscle may be given medicines to reduce the strain on the heart and ease symptoms.

The following medicines may be prescribed when mitral regurgitation symptoms get worse:

- Beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, or calcium channel blockers

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants) to help prevent blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation

- Medicines that help control uneven or abnormal heartbeats

- Water pills (diuretics) to remove excess fluid in the lungs

A low-sodium diet may be helpful. You may need to limit your activity if symptoms develop.

Once the diagnosis is made, you should visit your provider regularly to track your symptoms and heart function.

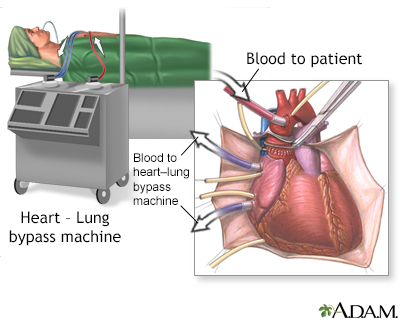

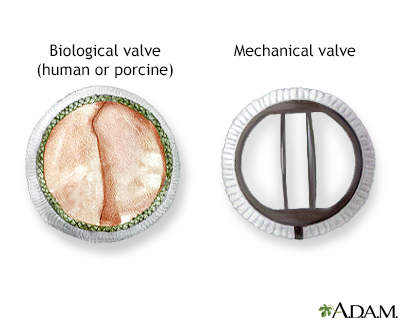

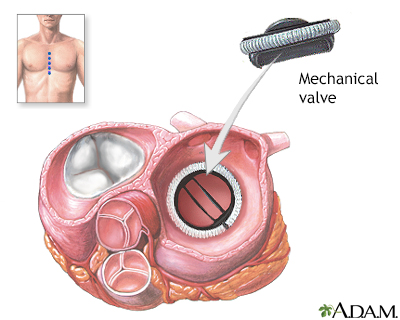

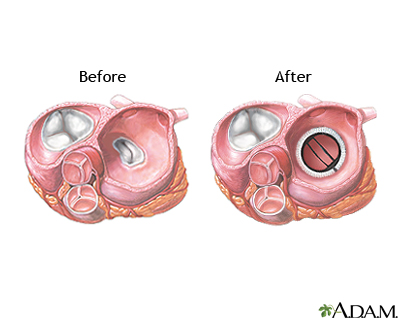

You may need surgery to repair or replace the valve if:

Surgery to repair or replace the valve

Mitral valve surgery is surgery to either repair or replace the mitral valve in your heart. Blood flows from the lungs and enters a pumping chamber o...

- Heart function is poor

- The heart becomes enlarged (dilated)

- Symptoms get worse

Catheter based non-surgical techniques to place clips or replace the mitral valve are increasingly in use for some selected patients with mitral regurgitation.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The outcome varies. Most of the time the condition is mild, so no therapy or restriction is needed. Symptoms can most often be controlled with medicine.

Possible Complications

Problems that may develop include:

-

Abnormal heart rhythms, including atrial fibrillation and possibly more serious, or even life-threatening abnormal rhythms

Abnormal heart rhythms

An arrhythmia is a disorder of the heart rate (pulse) or heart rhythm. The heart can beat too fast (tachycardia), too slow (bradycardia), or irregul...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Clots that may travel to other areas of the body, such as the lungs or brain

- Infection of the heart valve

-

Heart failure

Heart failure

Heart failure is a condition in which the heart is no longer able to pump oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body efficiently. This causes symptom...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if symptoms get worse or do not improve with treatment.

Also contact your provider if you are being treated for this condition and develop signs of infection, which include:

- Chills

- Fever

- General ill feeling

- Headache

- Muscle aches

Prevention

People with abnormal or damaged heart valves are at risk for an infection called endocarditis. Anything that causes bacteria to get into your bloodstream can lead to this infection. Steps to avoid this problem include:

- Avoid unclean injections.

- Treat strep infections quickly to prevent rheumatic fever.

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is a disease that may develop after an infection with group A streptococcus bacteria (such as strep throat or scarlet fever). It can...

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Always tell your provider and dentist if you have a history of heart valve disease or congenital heart disease before treatment. Some people may need antibiotics before dental procedures or surgery.

References

Carabello BA, Kodali S. Valvular heart disease. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 60.

Hahn RT, Bonow RO. Mitral regurgitation. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 76.

Writing Committee Members, Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162(2):e183-e353. PMID: 33972115 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33972115/.

-

Valvular heart disease (VHD) overview

Animation

-

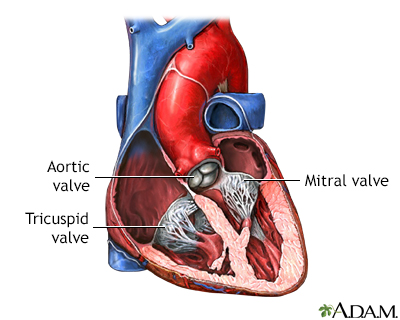

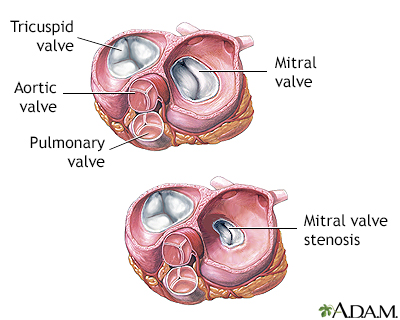

Heart - section through the middle - illustration

The interior of the heart is composed of valves, chambers, and associated vessels.

Heart - section through the middle

illustration

-

Heart - front view - illustration

The external structures of the heart include the ventricles, atria, arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart while veins carry blood into the heart. The vessels colored blue indicate the transport of blood with relatively low content of oxygen and high content of carbon dioxide. The vessels colored red indicate the transport of blood with relatively high content of oxygen and low content of carbon dioxide.

Heart - front view

illustration

-

Heart valve surgery - Series

Presentation

-

Heart - section through the middle - illustration

The interior of the heart is composed of valves, chambers, and associated vessels.

Heart - section through the middle

illustration

-

Heart - front view - illustration

The external structures of the heart include the ventricles, atria, arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart while veins carry blood into the heart. The vessels colored blue indicate the transport of blood with relatively low content of oxygen and high content of carbon dioxide. The vessels colored red indicate the transport of blood with relatively high content of oxygen and low content of carbon dioxide.

Heart - front view

illustration

-

Heart valve surgery - Series

Presentation

Review Date: 2/27/2024

Reviewed By: Thomas S. Metkus, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.