Tricuspid regurgitation

Tricuspid insufficiency; Heart valve - tricuspid regurgitation; Valvular disease - tricuspid regurgitationBlood that flows between different chambers of your heart must pass through a heart valve. These valves open up enough so that blood can flow through. They then close, keeping blood from flowing backward.

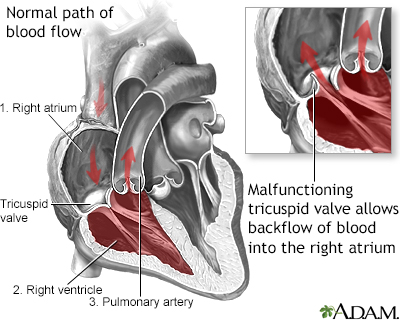

The tricuspid valve separates the right lower heart chamber (the right ventricle) from the right upper heart chamber (right atrium).

Tricuspid regurgitation is a disorder in which this valve does not close tight enough. This problem causes blood to flow backward into the right upper heart chamber (atrium) when the right lower heart chamber (ventricle) contracts.

Causes

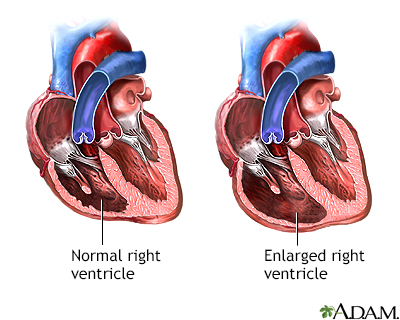

An increase in size of the right ventricle is the most common cause of this condition. The right ventricle pumps blood to the lungs where it picks up oxygen. Any condition that puts extra strain on this chamber can cause it to enlarge. Examples include:

- Abnormally high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs which can come from a lung problem (such as COPD, or a clot that has traveled to the lungs)

- Other heart problem such as poor squeezing of the left side of the heart

- Problem with the opening or closing of another one of the heart valves

Tricuspid regurgitation may also be caused or worsened by infections, such as:

- Rheumatic fever

- Infection of the tricuspid heart valve, which causes damage to the valve

Less common causes of tricuspid regurgitation include:

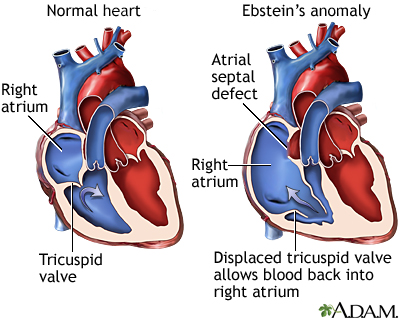

- A type of heart defect present at birth called Ebstein anomaly.

- Carcinoid tumors, which release a hormone that damages the valve.

- Marfan syndrome

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

- Radiation therapy.

- Past use of a diet pill called "Fen-Phen" (phentermine and fenfluramine) or dexfenfluramine. The drug was removed from the market in 1997.

Symptoms

Mild tricuspid regurgitation may not cause any symptoms. Symptoms of heart failure may occur, and can include:

- Active pulsing in the neck veins

- Decreased urine output

Urine output

Decreased urine output means that you produce less urine than normal. Most adults make at least 500 milliliters of urine in 24 hours (a little over ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article -

Fatigue, tiredness

Fatigue

Fatigue is a feeling of weariness, tiredness, or lack of energy.

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - General swelling

-

Swelling of the abdomen

Swelling of the abdomen

A swollen abdomen is when your belly area is bigger than usual.

Read Article Now Book Mark Article -

Swelling of the feet and ankles

Swelling of the feet

Painless swelling of the feet and ankles is a common problem, especially among older people. Abnormal buildup of fluid in the ankles, feet, and legs ...

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article

ImageRead Article Now Book Mark Article - Weakness

Exams and Tests

The health care provider may find abnormalities when gently pressing with the hand (palpating) on your chest. The provider may also feel a pulse over your liver. The physical exam may show liver and spleen swelling.

Palpating

Palpation is a method of feeling with the fingers or hands during a physical examination. The health care provider touches and feels your body to ex...

Listening to the heart with a stethoscope may reveal a murmur or other abnormal sounds. There may be signs of fluid buildup in the abdomen.

An ECG or echocardiogram may show enlargement of the right side of the heart. Doppler echocardiography or right-sided cardiac catheterization may be used to measure blood pressure inside the heart and lungs.

ECG

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is a test that records the electrical activity of the heart.

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram is a test that uses sound waves to create pictures of the heart. The picture and information it produces is more detailed than a s...

Cardiac catheterization

Cardiac catheterization involves passing a thin flexible tube (catheter) into the right or left side of the heart. The catheter is most often insert...

Other tests, such as CT scan or MRI of the chest (heart), may reveal enlargement of the right side of the heart and other changes.

Treatment

Treatment may not be needed if there are few or no symptoms. You may need to go to the hospital to diagnose and treat severe symptoms.

Swelling and other symptoms of heart failure may be managed with medicines that help remove fluids from the body (diuretics).

Some people may be able to have surgery to repair or replace the tricuspid valve. Surgery is most often done as part of another procedure.

Treatment of certain conditions may correct this disorder. These include:

- High blood pressure in the lungs

- Swelling of the right lower heart chamber

Outlook (Prognosis)

Surgical valve repair or replacement most often provides a cure in people who need an intervention.

The outlook is poor for people who have symptomatic, severe tricuspid regurgitation that cannot be corrected.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have symptoms of tricuspid regurgitation.

Prevention

People with abnormal or damaged heart valves are at risk for an infection called endocarditis. Anything that causes bacteria to get into your bloodstream may lead to this infection. Steps to avoid this problem include:

- Avoid unclean injections.

- Treat strep infections promptly to prevent rheumatic fever.

- Always tell your health care provider and dentist if you have a history of heart valve disease or congenital heart disease before treatment. Some people may need to take antibiotics before having a procedure.

Prompt treatment of disorders that can cause valve or other heart diseases reduces your risk for tricuspid regurgitation.

References

Carabello BA. Valvular heart disease. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 66.

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e35-e71. PMID: 33332149 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33332149/.

Pellikka PA, Nkomo VT. Tricuspid, pulmonic, and multivalvular disease. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 77.

Rosengart TK, Aberle CM, Ryan C. Acquired heart disease: valvular. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 61.

-

Valvular heart disease (VHD) overview

Animation

-

Tricuspid Regurgitation - illustration

Tricuspid regurgitation is a disorder involving backflow of blood from the right ventricle to the right atrium during contraction of the right ventricle. It is caused by damage to the tricuspid heart valve or enlargement of the right ventricle.

Tricuspid Regurgitation

illustration

-

Tricuspid Regurgitation - illustration

Tricuspid regurgitation is a disorder involving backflow of blood from the right ventricle to the right atrium during contraction of the right ventricle. The most common cause of tricuspid regurgitation is not damage to the valve itself but enlargement of the right ventricle, which may be a complication of any disorder that causes right ventricular failure.

Tricuspid Regurgitation

illustration

-

Ebstein's anomaly - illustration

Ebstein's anomaly is a congenital heart condition which results in an abnormality of the tricuspid valve. In this condition the tricuspid valve is elongated and displaced downward towards the right ventricle. The abnormality causes the tricuspid valve to leak blood backwards into the right atrium.

Ebstein's anomaly

illustration

-

Tricuspid Regurgitation - illustration

Tricuspid regurgitation is a disorder involving backflow of blood from the right ventricle to the right atrium during contraction of the right ventricle. It is caused by damage to the tricuspid heart valve or enlargement of the right ventricle.

Tricuspid Regurgitation

illustration

-

Tricuspid Regurgitation - illustration

Tricuspid regurgitation is a disorder involving backflow of blood from the right ventricle to the right atrium during contraction of the right ventricle. The most common cause of tricuspid regurgitation is not damage to the valve itself but enlargement of the right ventricle, which may be a complication of any disorder that causes right ventricular failure.

Tricuspid Regurgitation

illustration

-

Ebstein's anomaly - illustration

Ebstein's anomaly is a congenital heart condition which results in an abnormality of the tricuspid valve. In this condition the tricuspid valve is elongated and displaced downward towards the right ventricle. The abnormality causes the tricuspid valve to leak blood backwards into the right atrium.

Ebstein's anomaly

illustration

Review Date: 1/9/2022

Reviewed By: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.