Acute lymphocytic leukemia - InDepth

ALL - InDepth; Acute lymphoblastic leukemia - InDepth; Acute lymphoid leukemia - InDepth; Acute childhood leukemia - InDepth; Cancer - acute childhood leukemia (ALL) - InDepth; Leukemia - acute childhood (ALL) - InDepth; Acute lymphocytic leukemia - InDepthAn in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of leukemia.

Highlights

Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia or Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

There are four major types of leukemia. ALL is the most common in children, and the least common in adults. About 6,000 people are diagnosed with ALL each year. Children account for two thirds of these cases. In general, children with ALL have a better outlook than adults. Most children with ALL can be cured of this cancer.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Symptoms of ALL include fatigue, pale skin, recurrent infections, bone pain, bruising, and small red spots under the skin. Doctors use various tests, including blood counts and bone marrow biopsies, to diagnose ALL.

Treatment

ALL is treated with chemotherapy and, sometimes, radiation. Children receive different chemotherapy regimens than adults. Some people with advanced cancer that has not responded to these treatments may need a stem cell transplant.

Infection Prevention

Both chemotherapy and transplantation increase the risk for infection. People must take strict precautions to avoid exposure to germs. Ways to prevent infection include:

- Practice good hygiene including regular handwashing and dental care (such as brushing and flossing).

- Avoid crowds, especially during cold and flu season.

- Eat only well-cooked foods (no raw fruits or vegetables or undercooked poultry, meat, or fish).

- Boil tap water before drinking it.

- Do not keep fresh flowers or plants in the house as they may carry mold.

- Keep up to date with vaccinations. People may benefit from repeat or booster immunizations.

Introduction

The word leukemia literally means "white blood" and is used to describe a variety of cancers that form in the white blood cells (lymphocytes) of the bone marrow. Bone marrow is the soft tissue in the center of the bones, where blood cells are produced. The bone marrow makes white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets.

White blood cells are an essential part of the immune system. They are used by the body to fight infections and other foreign substances. The general name for white blood cells is leukocytes. Lymphocytes are a specific type of leukocyte. Leukocytes evolve from immature cells referred to as blasts. Immature lymphocytes are called lymphoblasts. Malignancy of these blast cells is the source of leukemias.

Both leukemia and lymphomas (Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphomas) are cancers of leukocytes. The difference is that leukemia starts in the bone marrow while lymphomas originate in lymph nodes and then spread to the bone marrow or other organs.

Leukemias are classified based on how quickly they progress and the development of the cells.

- Acute leukemia progresses quickly with many immature white cells.

- Chronic leukemia progresses more slowly and has more mature white cells.

There are four major types of leukemia:

- Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL)

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

- Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is the focus of this report.

All leukemias involve an uncontrolled increase in the number of white blood cells. In acute leukemias, the bone marrow produces an overwhelming number of immature cells. These cancerous cells prevent healthy red cells, platelets, and mature white cells (leukocytes) from being made in the bone marrow. Life-threatening symptoms can then develop.

Cancer cells can spread to the bloodstream and lymph nodes. They can also travel to the brain and spinal cord (the central nervous system) and other parts of the body.

Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is also known as acute lymphoid leukemia or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The majority of childhood leukemias are of the ALL type.

Lymphocytes are the body's primary immune cells. Among other vital functions, lymphocytes produce antibodies, factors that can target and attack specific foreign substances (antigens) and fight infections.

Lymphocytes develop in the thymus gland or bone marrow and are therefore categorized as either B cells (bone marrow-derived cells) or T cells (thymus gland-derived cells). ALL can arise from either T-cell or B-cell lymphocytes. Most cases of ALL involve B cells.

Causes

It is likely that ALL develops from a combination of genetic, biological, and environmental factors.

Genetic Translocations

Many leukemias involve genetic rearrangements, called translocations, in which some of the genetic material (genes) on a chromosome may be shuffled or swapped between a pair of chromosomes.

Translocations commonly associated with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) include:

- Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome is the most common genetic translocation, where DNA is swapped between chromosomes 9 and 22 [t(9:22)]. It occurs more often in adults than in children with ALL. ALL that is Philadelphia chromosome-positive is generally more difficult to treat.

- TEL-AML1 fusion, also referred to as t(12;21) is another common translocation. It generally indicates a favorable prognosis.

- Other translocations may occur in ALL, including t(17;19) and t(9;12).

Risk Factors

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is diagnosed in about 6,000 Americans each year. Children account for two thirds of these new cases.

Age

ALL in Children

ALL is the most common type of cancer diagnosed in children. ALL accounts for about 75% of cases of childhood leukemia. ALL can occur in children of all ages. But it is most likely to occur before age 5 years. It is slightly more common in boys than in girls.

ALL in Adults

ALL is the least common type of leukemia among adults. About 1 in 3 cases of ALL occur in adults. Adults over age 50 have a higher risk for ALL than those between the ages of 20 and 50.

Race and Ethnicity

White and Hispanic children have a higher risk for ALL than African American children.

Hereditary Disorders

ALL does not appear to run in families. Still, certain genetic disorders may increase risk. For example, children with Down syndrome have a 20-times greater risk of developing ALL than the general population. Other rare genetic disorders associated with increased risk include Klinefelter syndrome, Bloom syndrome, Fanconi anemia, ataxia-telangiectasia, neurofibromatosis, Shwachman syndrome, IgA deficiency, and congenital X-linked agammaglobulinemia.

Radiation and Chemical Exposure

Previous cancer treatment with high doses of radiation or chemotherapy can increase the risk for developing ALL. Prenatal exposure to x-rays may also increase the risk in children. Lower levels of radiation (living near power lines, video screen emissions, small appliances, cell phones) are unlikely to pose any cancer risk.

Symptoms

The symptoms of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) may be difficult to recognize. ALL usually begins abruptly and intensely, but in some cases symptoms may develop slowly. They may be present one day, and absent the next, particularly in children.

Leukemia symptoms are due to a lack of normal healthy cells in the blood. Some symptoms of ALL are very general and can mimic those of other disorders. Other symptoms are very specific to leukemia. For example, problems with bleeding and bruising are caused by a low count of blood-clotting (platelet) cells. Problems with frequent infections are due to the reduced numbers of healthy mature white blood cells (leukocytes).

General symptoms of ALL include:

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Recurrent minor infections

- Shortness of breath during normal activities

Other symptoms of ALL include:

- Paleness. People may be pale and fatigued from anemia caused by insufficient red blood cells.

- Bruising and bleeding may result from only slight injury. Small red spots (petechiae) may appear on the skin.

- Pain in bones and joints is common as is abdominal pain and swelling.

- Swollen lymph nodes may appear under arms, in groin, and in neck.

Diagnosis

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is diagnosed based on various tests.

Physical Examination

The doctor will examine the person for signs of enlarged lymph nodes or enlarged liver or spleen. The doctor will also look for any signs of bruising or bleeding.

Blood Tests

A complete blood cell count (CBC), which checks for numbers of white cells, red blood cells, and platelets, is the first step in diagnosing ALL. People with ALL generally have a higher than normal white blood count and lower than normal red blood cell and platelet counts.

Blood tests are also performed to evaluate liver, kidney, and blood clotting status and to check for levels of certain minerals and proteins.

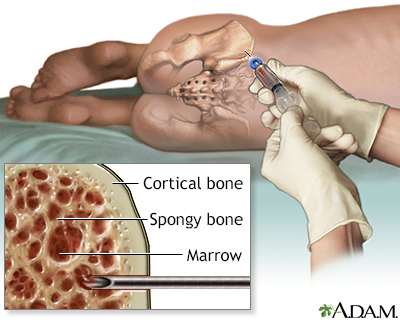

Bone Marrow Biopsy

If blood test results are abnormal or the doctor suspects leukemia despite normal cell counts, a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are the next steps. These are very common and safe procedures. However, because this test can produce considerable anxiety, particularly in children, parents may want to ask the doctor if sedation is appropriate for their child.

- A local anesthetic is given.

- A needle is inserted into the bone, usually the rear hipbone. There may be brief pressure or pain. A small amount of marrow is withdrawn. Marrow looks like blood.

- A larger needle is then inserted into the same place and pushed down to the bone. The doctor will rotate the needle to obtain a specimen for the biopsy. The person will feel some pressure.

- The sample is then taken to the lab to be analyzed. All the results are completed within a couple of days.

Normal bone marrow contains 5% or less of blast cells (the immature cells that ordinarily develop into healthy blood cells). In leukemia, abnormal blasts constitute between 20% to 100% of the marrow.

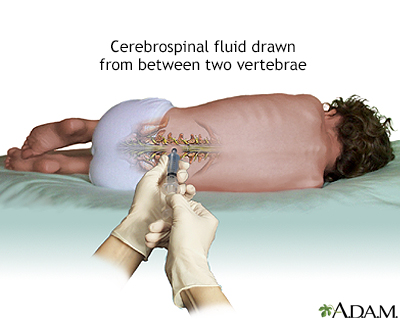

Spinal Tap

If bone marrow examination confirms ALL, a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) may be performed, which uses a needle inserted into the spinal canal. The person feels some pressure and usually must lie flat for about an hour afterward to prevent a severe headache. This can be difficult, particularly for children, so parents should plan reading or other quiet activities that will divert the child during that time. Parents should also be certain that the doctor performing this test is experienced in this procedure.

A sample of cerebrospinal fluid with leukemia cells is a sign that the disease has spread to the central nervous system. In most cases of childhood ALL, leukemia cells are not found in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Tests Performed after Diagnosis

Once a diagnosis of leukemia has been made, further tests are performed on the bone marrow cells:

- Cytochemistry, flow cytometry, immunocytochemistry, immunophenotyping, and next generation sequencing are tests that are used to identify and classify specific types of leukemia. For example, cytochemistry distinguishes lymphocytic leukemia cells from myeloid leukemia cells. Immunophenotyping shows if ALL cells are T cells or B cells based on the antigen located on the surface of the cell.

- Cytogenetics, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), and next generation sequencing are used for genetic analysis. Cytogenetic testing can detect translocations (such as Philadelphia chromosome) and other genetic abnormalities. FISH is used to identify specific changes within chromosomes. Next Generation Sequencing identifies mutations. Genetic mutations and variations may help determine selection of and response to treatment.

Cell Classification

The results of cytogenetic, flow cytometry, immunophenotyping, and other tests can help provide information on types and subtypes of ALL cells. The particular subtype of cell can aid in determining prognosis and treatment.

An older classification system called the French-American-British (FAB) classification grouped ALL into L1, L2, and L3 subtypes. A newer classification system classifies ALL B cells or T cells based on their stage of maturity.

B-Cell ALL Subtype Classification:

- Early Pre-B

- Common ALL

- Pre-B ALL

- Mature B-cell ALL (Also called Burkitt leukemia)

T-Cell ALL Subtype Classification:

- Pre-T ALL

- Mature T-cell ALL

Prognosis

Acute lymphocytic leukemia can progress quickly if untreated. However, ALL is one of the most curable cancers and survival rates are now at an all-time high.

Certain factors help determine prognosis:

- Age. Children have a better chance for recovery than adults. More than 95% of children with ALL attain remission. Among adults, younger people (especially those younger than age 50) have a better prognosis than older people.

- Initial white blood cell (WBC) count. People diagnosed with a WBC count below 50,000 tend to do better than people with higher WBC counts.

- ALL subtype. The subtype of T cell or B cell affects prognosis. For example, people with T-cell ALL tend to have a better prognosis than those with mature B-cell ALL (Burkitt leukemia).

- Chromosome translocations. People who have Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL tend to have a poorer prognosis, although the latest treatments are helping many of these people achieve remission. Chromosome abnormalities that lead to a poorer prognosis are t(4;11) and t(9;22).

- Response to chemotherapy. People who achieve complete remission (absence of active cancer) within 4 to 5 weeks of starting treatment tend to have a better prognosis than those who take longer. People who do not achieve remission at any time have a poorer prognosis. Evidence of minimal residual disease (presence of leukemia cells in the bone marrow) may also affect prognosis.

Other factors, such as central nervous system involvement or recurrence, may indicate a poorer prognosis.

Treatment

Treatment Phases

There are typically three treatment stages for the average-risk person with ALL:

- Induction therapy is given in order to achieve a first remission (the absence of active cancer)

- Consolidation (intensification) therapy is given to prevent relapse after remission has been achieved

- Maintenance treatment is lower intensity therapy given for several years to prevent relapse after remission

Because leukemia can also spread to the brain and spinal cord, where chemotherapy that is given intravenously or orally does not penetrate very well, most people also need radiation to the brain and spinal cord, or chemotherapy that is injected into the layers around them. This is called central nervous system prophylaxis (preventive treatment) and is given during all treatment phases to prevent the cancer from spreading to the brain and spinal cord.

Specific Treatments Used in ALL

The following are specific treatments used for ALL:

- Chemotherapy is the primary treatment for each stage. Newer drugs known as biological therapies are also being used.

- Radiation to the brain and spinal cord is also administered in some cases.

- A stem cell transplant may be recommended for some adults after treatment when there is no active cancer (remission) or for adults and children if the cancer has returned after treatment (relapsed).

Investigational Treatments

Enrolling in a clinical trial may be an option for some people. Scientists are working on finding new treatment options for ALL, including difficult to treat subtypes.

In 2013, researchers announced promising results from two clinical trials that involved a small number of adults and children with B-cell ALL. The trials tested an investigational treatment called targeted immunotherapy or more specifically, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T). This cell therapy involves filtering T-cells from a person, and then genetically transforming the cells by introducing a special gene. The genetically engineered T-cells are then infused back into the person, where they target and attack the cancerous B cells.

As a result of the above research, in August 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) for certain pediatric and young adults with B-cell precursor ALL that is refractory or in second or later relapse.

Treatment to Achieve Remission (Induction Therapy)

The aim of induction therapy, the first treatment phase, is to reduce the number of leukemia cells to undetectable levels. The general guidelines for induction therapy are as follows:

- People are given intensive chemotherapy that uses powerful multi-drug regimens. (Infants require special regimens not discussed here.)

- For both children and adults, some of these therapies are administered orally, others intravenously.

- Hospitalization is usually necessary at some point to help prevent infection and to give transfusions of blood, platelets, and other blood products. However, much of this therapy can be given on an outpatient basis.

- After the first cycle of induction, bone marrow tests are done to determine if the person is in remission.

- Another bone marrow test is sometimes performed about a week later to confirm the first results.

- A bone marrow transplant is considered for select people who do not respond to induction treatment.

Drugs Used for Induction

Both children and adults typically start with a 3-drug regimen. Imatinib (Gleevec) or dasatinib (Sprycel) may be added for people with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL.

For children, the standard drugs are:

- Vincristine (Oncovin), a vinca alkaloid drug.

- Prednisone or dexamethasone. These drugs are corticosteroids.

- Asparaginase. It is generally provided as pegaspargase (Oncaspar) or calaspargase pegol-mknl (Asparlas) rather than L-asparaginase (Elspar) for treating newly diagnosed ALL in children.

For adults, the standard drugs are:

- Vincristine.

- Prednisone or dexamethasone.

- Anthracycline drugs, such as such as doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or epirubicin. Some adult chemotherapy regimens also add on an asparaginase drug or cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan).

- Methotrexate.

- Cytarabine.

- Rituximab (Rituxan), an antibody targeting leukemia cells with CD20, is often added to chemotherapy in adults under 60 years of age.

Preventing Central Nervous System Disease (CNS Prophylaxis)

Chemotherapy given intravenously or orally does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier sufficiently to destroy leukemic cells in the brain. Since the brain is one of the first sites for relapsing leukemia, preventive treatment is administered to the brain and spine (called sanctuary disease sites). This is called CNS prophylaxis.

For children, CNS prophylaxis uses intrathecal chemotherapy, in which a drug is injected directly into the spinal fluid. Intrathecal chemotherapy is given with methotrexate (MTX), cytarabine, and hydrocortisone.

Some high-risk children may receive radiation to the skull (cranial radiation), radiation to the spine, or both along with intrathecal chemotherapy. This combination can be very toxic and is generally used only in children who have evidence of the disease in the central nervous system at the time of diagnosis. Long-term complications of high-dose cranial radiation can include learning and neurologic problems. Cranial radiation is also associated with increased risks for stroke and secondary cancers.

Adult CNS prophylaxis is performed in one of three ways:

- Cranial radiation plus intrathecal chemotherapy with methotrexate

- High-dose systemic infusion of methotrexate

- Intrathecal methotrexate or cytarabine chemotherapy alone

Evidence of Remission after Induction Treatment

Survival in acute leukemia depends on complete remission (no signs of active cancer). Although not always clear-cut, remission is indicated by the following:

- All signs and symptoms of leukemia disappear.

- There are no abnormal cells in the blood, bone marrow, and cerebrospinal fluid.

- The percentage of blast cells in the bone marrow is less than 5%.

- Blood platelet count returns to normal.

Induction can produce extremely rapid results. Nearly all children with ALL achieve remission after a month of induction treatment. The shorter the time to remission the better the outlook:

- A complete remission usually occurs within the first 4 weeks. People who show low disease levels within 7 to 14 days have an excellent outlook, particularly if they have favorable genetic factors, and may need less-intensive treatments afterward.

- People with high disease levels at 14 days or who require more than 4 weeks to achieve remission are at higher risk for relapse and most likely need more aggressive treatment.

Side Effects and Complications

Side effects and complications of any chemotherapeutic regimen and radiation therapy are common, are more severe with higher doses, and increase over the course of treatment. Administering drugs for shorter duration can sometimes reduce toxicities without affecting the drugs' cancer-killing effects.

Common Side Effects

Typical side effects include:

- Nausea and vomiting. Drugs known as serotonin antagonists, such as ondansetron (Zofran) or granisteron (Kyril), can relieve these side effects.

- Diarrhea.

- Hair loss.

- Mouth sores.

- Weight loss.

- Depression.

Serious Side Effects

Serious side effects can also occur and may vary depending on the specific drugs used.

Infection from suppression of the immune system or from severe drops in white blood cells is a common and serious side effect. People should make all efforts to prevent infection. The person at high risk for infection may need potent antibiotics and antifungal medications as well as granulocyte colony-stimulating factors or G-CSF (lenograstim, filgrastim) to stimulate the growth of infection-fighting white blood cells. People should make all efforts to minimize exposure to bacteria and viruses. (See "Preventing Infection" in the Home Management section of this report.)

Other serious side effects may include:

- Liver and kidney damage

- Very high levels of uric acid in the blood, which can damage the kidneys

- Very high levels of calcium in the blood, which can impair heart function

- Abnormal blood clotting

- Suppression of adrenal glands in children who take short-term, high-dose corticosteroids such as prednisolone

- Dasatinib can increase the risk for increased pressure in the arteries of the lungs (pulmonary arterial hypertension)

Long-Term Complications

- Fatigue is very common after chemotherapy and can be significant and long-lasting.

- Combinations of intrathecal chemotherapy plus brain radiation in children can cause some serious complications, including seizures and problems in learning and concentration.

- Delayed puberty. The effects of treatment in the brain can affect regions that regulate reproductive hormones, which may affect fertility later on. Chemotherapy, cranial radiation, or both can impair fertility in men and women. Cranial radiation can also result in impaired growth.

- Bone density loss can occur after chemotherapy, particularly with corticosteroids and after bone marrow transplantation.

- Heart damage. Some of the treatments increase risk factors for future heart disease, including unhealthy cholesterol levels and high blood pressure. People treated for ALL should be regularly monitored for heart risks.

- Stroke. Survivors of childhood leukemia are at increased risk for later stroke, especially if they received treatment with cranial radiation.

- Secondary Cancers. Survivors of childhood ALL are at increased risk of later developing other types of cancers, including brain and spinal cord tumors, basal cell skin carcinoma, and myeloid (bone marrow) malignancies. Radiation and older types of chemotherapy are mainly responsible for this risk. Newer types of ALL treatment may be less likely to cause secondary cancers.

Treatment During Remission (Consolidation and Maintenance)

Consolidation and maintenance therapies follow induction and first remission. The goal of consolidation and maintenance therapies is to prevent a relapse.

Consolidation (Intensification) Therapy

Because there is a high risk of the cancer returning (relapsing) after the first phase of treatment (induction therapy), an additional course of treatment is given next. This is called consolidation therapy (also called intensification therapy). Consolidation is an intense chemotherapy regimen that is designed to prevent a relapse and usually continues for about 4 to 8 months.

Examples of consolidation regimens for people at standard risk:

- A limited number of courses of intermediate- or high-dose methotrexate.

- An anthracycline drug, such as daunorubicin (Cerubidine), used for reinduction followed by cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Neosar) 3 months after remission.

- Extended use of an asparaginase drug.

- Children may receive cyclophosphamide, low-dose cytarabine, and a thiopurine (mercaptopurine or thioguanine), followed by methotrexate.

More intense regimens are used for people at high-risk for relapse.

Maintenance

The last phase of treatment is maintenance (also called continuation therapy):

- Maintenance therapy typically uses weekly administration of methotrexate (usually in oral form) and daily doses of mercaptopurine.

- If CNS prophylaxis was not given before, it may be given now.

- Vincristine and a corticosteroid drug (generally dexamethasone) may be added to standard maintenance therapy.

A maintenance regimen is usually less toxic and easier to tolerate than induction and consolidation. Maintenance treatment lasts for about 2 to 3 years for most people with ALL. It is not clear if maintenance therapy benefits people who have certain specific types of ALL, such as T-cell ALL or mature B-cell ALL (Burkitt leukemia).

Treatment After Relapse

Relapse is when cancer returns after remission. Most people with ALL achieve remission after induction therapy, but in some people the disease returns.

The following are factors that increase the risk for relapse after initial treatments:

- Microscopic evidence of leukemia after 20 weeks of therapy (minimal disease).

- Age over 30.

- A high white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis.

- Disease that has spread beyond the bone marrow to other organs.

- Certain genetic abnormalities, such as the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome.

- People with high disease levels after 7 to 14 days of induction therapy.

- The need for 4 or more weeks of induction chemotherapy in order to achieve a first complete remission.

Treatment for relapse after a first remission may be standard chemotherapy or experimental drugs, or more aggressive treatments such as stem cell transplants.

The decision depends on a number of factors including how soon relapse occurs after treatment:

- Children who relapse 3 or more years after achieving a first complete remission usually achieve a second remission with a second round of standard chemotherapy treatments.

- Children who relapse within 6 months to 3 years following treatment may be able to achieve remission with a more aggressive course of chemotherapy.

- Children who relapse less than 6 months following initial treatment, or while on chemotherapy have a lower chance for a second remission. In such cases, stem cell transplantation may be considered. Stem cell transplantation is especially considered for children who relapse with T-cell ALL.

- Adults with ALL who experience a relapse following maintenance therapy are unlikely to be helped by additional chemotherapy alone. They are considered candidates for stem cell transplantation. Stem cell transplantation is also an option for adults, but not children, who have achieved a first remission.

Transplantation procedures are reserved for people with high-risk disease who are unlikely to achieve remission with chemotherapy alone. Transplantation does not offer any additional advantages for people at low or standard risk.

Chemotherapy and Other Drugs Used After Relapse

Many different types of drugs are used to treat ALL relapses. These drugs include chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine, asparaginase, anthracyclines (doxorubicin, daunorubicin), cyclophosphamide, cytarabine (ara-C), epipodophyllotoxins (etoposide, teniposide), and Marqibo, a specially-formulated type of vincristine injection, for adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative ALL. Other chemotherapeutic drugs for relapsed or refractory ALL include nelarabine (Arranon), for T-cell ALL, and clofarabine (Clolar), for pediatric ALL patients.

Immunotherapeutic drugs include blinatumomab (Blincyto) and inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa), both for B-cell precursor ALL.

The most recently approved approach to relapsed disease in the pediatric and young adult population is the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel), targeting a B-cell protein called CD19.

The drugs known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are also utilized in the relapsed setting. Tyrosine kinase is a growth-stimulating protein. TKI drugs block the cell signals that trigger cancer growth. TKI drugs approved for adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) ALL include: Imatinib (Gleevec), Dasatinib (Sprycel), Ponatinib (Iclusig), and Bosutinib (Bosulif).

Transplantation

Transplantation

Stem cells that are made in the bone marrow are the early form of all blood cells in the body. They normally mature into red, white, or immune cells. To help the person survive high dose chemotherapy needed to cure leukemia that has returned treatment, or not responded to treatment, a stem cell transplantation procedure may be used. Stem cell transplantation replaces blood stem cells that were lost during the initial chemotherapy treatment. The lost stem cells are replaced by transplanting them from a donor into the person.

Types of Donors

The stem cells to be given to the person with leukemia can come from either the patient (autologous) or a donor (allogeneic):

- Allogeneic transplant. In an allogeneic transplant, the stem cells are taken from another person or donor. The immune system of the person receiving the new cells will usually try to reject these new, foreign cells. The more the donor cells are genetically similar, the less likely the person receiving the cells will reject them. Allogeneic transplants that are from genetically matched sibling donors offer the best results in ALL. With new techniques, donor bone marrow from unrelated but immunologically similar donors is proving to work as well as those from matched siblings.

- Autologous transplant. If the marrow or blood cells used are the person's own, the transplant is called autologous. Autologous transplants in people with ALL are generally not beneficial, since there is some danger that the cells used may contain tumor cells and the cancer can regrow. Treatment advances that reduce this risk, however, may make autologous transplantation feasible in people without family donors.

The Blood Stem Cell Collection Procedure

Sources of Cells

Stem cells can be obtained either from the donor's:

- Bone marrow (bone marrow transplantation)

- Blood (peripheral blood stem cell transplantation)

The Transplant Procedure

- The person with ALL is given high-dose chemotherapy with or without radiation -- a treatment known as conditioning. The point is to inactivate the immune system and to kill any remaining leukemia cells.

- A few days after treatment, the person is rescued using the stored stem cells, which are administered through a vein. This may take several hours. People may experience fever, chills, hives, shortness of breath, or a fall in blood pressure during the procedure.

- The person is kept in a protected environment to minimize infection, and the person usually needs blood cell replacement and nutritional support.

Side Effects and Complications

Stem-cell transplantation is a serious and complex procedure that can cause many short- and long-term side effects and complications.

Early side effects of transplantation are similar to chemotherapy and include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, mouth sores, and loss of appetite. Bleeding because of reduced platelets is a high risk during the first month, people may require blood transfusions.

Later side effects can include fertility problems (if the ovaries are affected), thyroid gland problems (which can affect metabolism), lung damage (which can cause breathing problems) and bone damage.

Two of the most serious complications of transplantation are infection and graft-versus-host disease:

Infection resulting from a weakened immune system is the most common danger. The risk for infection is most critical during the first 6 weeks following the transplant, but it takes 6 to 12 months post-transplant for a person's immune system to fully recover. Many people develop severe herpes zoster virus infections (shingles) or have a recurrence of herpes simplex virus infections (cold sores and genital herpes). Pneumonia and infections with germs that normally do not cause serious infections such as cytomegalovirus, aspergillus (a type of fungus), and Pneumocystis jiroveci (a fungus) are among the most serious life-threatening infections.

It is very important that people take precautions to avoid post-transplant infections. (See Home Management section of this report.)

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

GVHD is a serious attack by the person's immune system triggered by the donated new marrow in allogeneic transplants.

Acute GVHD occurs in 30% to 50% of allogeneic transplants, usually within 25 days. Its severity ranges from very mild symptoms to a life-threatening condition (more often in older people). The first sign of acute GVHD is a rash, which typically develops on the palms of hands and soles of feet and can then spread to the rest of the body. Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, diarrhea, loss of appetite and jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes). To prevent acute GVHD, doctors use immune-suppressing drugs such as steroids, methotrexate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and monoclonal antibodies.

Chronic GVHD can develop 70 to 400 days after the allogeneic transplant. Initial symptoms include those of acute GVHD. Skin, eyes, and mouth can become dry and irritated, and mouth sores may develop. Chronic GVHD can also sometimes affect the esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, and liver. Bacterial infections and chronic low-grade fever are common. Chronic GVHD is treated with similar medicines as acute GVHD.

Too much sun exposure can trigger GVHD. It is important for people to always wear sunscreen (SPF 15 or higher) on areas of the skin that are exposed to the sun. When outside, try to stay in the shade.

Home Management

A parent should call the doctor if the child has any symptoms that are out of the ordinary, including (but not limited) to:

- Any fever of 101°F (38.3°C) or higher

- Any signs of a flu or cold

- Shortness of breath

- Severe diarrhea

- Blood in the urine or stools

- Trouble urinating

Tracking Neutrophils

Parents should track their child's absolute neutrophil count. This measurement for the amount of white blood cells is an important gauge of a child's ability to fight infection.

- Counts over 1,000 usually provide sufficient protection so that children can engage in normal activities, including school and other functions where they are exposed to other children.

- If the count is between 500 and 1,000, the child should avoid large groups.

- If it falls between 200 and 500, the child should stay at home and should see only healthy visitors who have washed their hands vigorously.

- Neutrophil counts below 200 indicate that the child is at high risk for infection and should have no visitors.

Preventing Infection

It is very important to take precautions to prevent infection following chemotherapy or transplantation. Guidelines for infection prevention and control include:

- Discuss with the doctor what vaccinations are needed and when. Children with ALL may need reimmunization. In general, it is best to have immunizations prior to chemotherapy and to avoid live virus vaccines during treatment.

- Avoid crowds, especially during cold and flu season.

- Be diligent about hand washing and make sure that visitors wash their hands. Alcohol-based hand rubs are best.

- Avoid eating raw fruits and vegetables. Poultry, meat, fish, eggs, and other foods should be cooked thoroughly. Do not eat foods purchased at salad bars or buffets. In the first few months after the transplant, be sure to eat protein-rich foods to help restore muscle mass and repair cell damage caused by chemotherapy and radiation.

- Boil tap water before drinking it.

- Dental hygiene is very important, including daily brushing and flossing. Use a soft toothbrush to prevent gum bleeding. Schedule regular visits with your dentist.

- Do not sleep with pets. Avoid contact with pets' excrement.

- Avoid fresh flowers and plants as they may carry mold. Do not garden.

- Swimming may increase exposure to infection. If you swim, do not submerge your face in water. Do not use hot tubs.

- Report to the doctor any symptoms of fever, chills, cough, difficulty breathing, rash or changes in skin, and severe diarrhea or vomiting. Fever is one of the first signs of infection. Some of these symptoms can also indicate graft-versus-host disease.

- Report to the ophthalmologist any signs of eye discharge or changes in vision. People who undergo radiation or who are on long-term steroid therapy have an increased risk for cataracts.

- Some of the drugs used for leukemia cause extreme sun sensitivity. Sunburn can cause skin infection. Children should wear sunblock and sun-protective clothing when going outside.

Resources

- Leukemia and Lymphoma Society -- www.lls.org

- American Cancer Society -- www.cancer.org

- National Cancer Institute -- www.cancer.gov

- American Society of Clinical Oncology -- www.asco.org

- ASCO Cancer.Net -- www.cancer.net

- American Childhood Cancer Organization -- www.acco.org

References

Appelbaum FR. Acute leukemias in adults. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 95.

Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, Version 2.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(7):882-913. PMID: 27407129 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27407129/.

Brown PA, Wieduwilt M, Logan A, et al. Guidelines Insights: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(5):414-423. PMID: 31085755 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31085755/.

Burns M, Armstrong SA, Gutierrez A. Pathology of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, et al, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 64.

Dinner S, Gurbuxani S, Jain N, Stock W. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, et al, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 66.

Hunger SP, Teachey DT, Grupp S, Aplenc R. Childhood leukemia. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 93.

Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1541-1552. PMID: 26465987 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26465987/.

Malard F, Mohty M. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1146-1162. PMID: 32247396 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32247396/.

Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(5):439-448. PMID: 29385370 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29385370/.

National Cancer Institute website. Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment (PDQ): Health Professional Version. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65727/. Updated July 22, 2020. Accessed September 17, 2020.

National Cancer Institute website. Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment (PDQ): Patient Version. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65844/. Updated March 11, 2020. Accessed September 17, 2020.

National Cancer Institute website. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment (PDQ): Health Professional Version. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65763/. Updated August 13, 2020. Accessed September 17, 2020.

National Cancer Institute website. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment (PDQ): Patient Version. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65947/. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2020.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. NCCN Guidelines Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. V1.2019. www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/all-patient.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2020.

Santiago R, Vairy S, Sinnett D, Krajinovic M, Bittencourt H. Novel therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(11):1081-1099. PMID: 28608730 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28608730/.

Tubergen DG, Bleyer A, Ritchey AK, Friehling E. The leukemias. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 522.

Review Date: 10/26/2020

Reviewed By: Todd Gersten, MD, Hematology/Oncology, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, Wellington, FL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.