Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma - InDepth

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Highlights

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma

The non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) are a group of cancers that develop in the body's lymphatic system. There are many different types of NHL. Most types of NHL involve B cells, while a small percentage involve T cells and rarely NK cells. Common types of B-cell NHL include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma.

Prognosis

NHL are classified as indolent (slow-growing) or aggressive (fast-growing). Aggressive lymphomas, such as DLBCL, are often curable. Indolent lymphomas, such as follicular lymphoma, are more difficult to treat and tend to recur after periods of remission. With the advancement of new treatments and drugs, survival rates for people with NHL have significantly improved.

Risk Factors

The risk of NHL increases with age. Most people are diagnosed when they are in their 60s and 70s. However, NHL can develop in people of any age, including children. People who have immune system impairment because of infections, disease, or exposure to certain types of chemicals appear to have increased risk. Still, people without any known risk factors can develop NHL.

Symptoms

The most common first sign of lymphomas is a painless enlargement of one or more lymph nodes, usually in the neck, armpits, or groin.

More generalized symptoms can include:

- Drenching night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever

Diagnosis

NHL is diagnosed based on the results of physical examination, blood tests, imaging tests, and biopsy. A lymph node biopsy is the definitive test for diagnosing NHL, determining the type of NHL, and distinguishing NHL from Hodgkin lymphoma.

Treatment

Radiation, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies (such as rituximab, or Rituxan), and targeted therapies are the main treatments for NHL. For some patients, stem cell transplantation may be an option. Recently, new chimeric T cell receptor (CAR-T) therapies such as or tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) and axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adults with certain types of NHL.

Introduction

Lymphomas are malignancies of the lymph system that are generally subdivided into two groups: Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for about 10% of all lymphomas, and NHL for the remaining 90% of lymphomas.

NHL is a term for malignancies that range from a very slow disease to an extremely aggressive but curable condition. They have certain features in common.

Lymphatic system

The lymphatic system filters fluid from around cells. It is an important part of the immune system. When people refer to swollen glands in the neck, they are usually referring to swollen lymph nodes. Common areas where lymph nodes can be easily felt, especially if they are enlarged, are the groin, armpits (axilla), above the clavicle (supraclavicular), in the neck (cervical), and the back of the head just above hairline (occipital).

The lymphatic system filters fluid from around cells. It is an important part of the immune system. When people say they have swollen glands in the neck, they are usually referring to enlarged lymph nodes. Common areas where lymph nodes can be easily felt, particularly if they are enlarged, include the groin, armpits (axilla), above the clavicle (supraclavicular), in the neck (cervical), and the back of the head just above the hairline (occipital).

The Lymphatic System

Lymphomas, such as NHL and Hodgkin lymphoma, represent tumors of the lymphatic system. This system is a network of organs, lymphatic vessels, and nodes. The lymphatic system interacts with the circulatory system to transport a watery clear fluid called lymph that is similar to the blood plasma throughout the body. Lymph is mainly composed of interstitial fluid but also contains waste products, cellular debris, as well as lymphocytes, important white blood cells involved in defending the body against infectious organisms.

Lymphocytes

One of the most important components of lymph is lymphocytes, a type of white blood cells (leukocytes) that is an essential part of the immune system:

- Lymphocytes develop in the bone marrow or thymus gland and are therefore categorized as either B cells (bone marrow-derived cells) or T cells (thymus gland-derived cells). They are transported throughout the body via blood.

- Lymphatic vessels begin as tiny tubes transporting interstitial fluid away from tissues. These vessels lead to larger lymphatic ducts and branches traveling toward the heart until they drain into two ducts in the neck, where the lymph enters the bloodstream.

- Along the way, the lymph passes through lymph nodes, oval structures composed of lymph vessels, connective tissue, and white blood cells. Here, lymphocytes are either filtered out or added to the contents of the node.

- Both leukemia and lymphomas (Hodgkin lymphoma and NHL) are cancers of leukocytes (white blood cells). The difference is that leukemia starts in the bone marrow while lymphomas originate in lymph nodes and then spread to the bone marrow or other organs.

Lymph Nodes

In lymph nodes, lymphocytes receive their initial exposure to foreign substances (antigens), such as bacteria or other microorganisms. This exposure activates the lymphocytes to produce antibodies, which are immune system factors that target and attack specific foreign proteins (antigens). The size of a lymph node varies from that of a pinhead to a bean. Most nodes are in clusters located throughout the body. Important node clusters are found in the neck, armpit, and groin.

Other Structures in the Lymphatic System

The tonsils and adenoids are secondary organs composed of masses of lymph tissue that also play a role in the lymphatic system. The spleen is another important organ that processes lymphocytes from incoming blood.

Immune system structures

The immune system protects the body from potentially harmful substances. The inflammatory response (inflammation) is part of innate immunity. It occurs when tissues are injured by bacteria, trauma, toxins, heat or any other cause.

Lymph tissue in the head and neck

Lymph nodes play an important part in the body's defense against infection. Swelling might occur even if the infection is trivial or not apparent.

Locations of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas

NHL occur most often in lymph nodes in the chest, neck, abdomen, tonsils, and the skin. NHL may also develop in sites other than lymph nodes such as the digestive tract, central nervous system, and around the tonsils.

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas Categories

There are more than 30 distinct types of NHL. Lymphomas are categorized in several ways:

- Indolent (slow-growing) or aggressive (fast-growing). Indolent and aggressive lymphomas are equally common in adults. Aggressive lymphomas are more common in children. Aggressive lymphomas tend to be more curable than indolent lymphomas.

- B cell or T cell. About 85% to 90% of NHL are B-cell subtypes, 10% to 15% are T-cell subtypes, and less than 1% are NK-cell lymphomas. This report focuses on B-cell lymphomas.

B-Cell Lymphomas

The following are common types of B-cell lymphoma.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBLC)

DLBCL is the most common type of NHL, accounting for about 30% of all NHL cases. It is an aggressive, fast-growing lymphoma that usually affects adults but can also occur in children. DLBCL can occur in lymph nodes or in organs outside of the lymphatic system. DLBCL includes several subtypes such as mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, and primary effusion lymphoma.

Follicular Lymphoma (FL)

FL is the 2nd most common type of lymphoma, accounting for about 20% of all NHL cases. It is usually indolent (slow growing), but about 20% to 50% of FLs transform over time into the aggressive DLBCL.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma is an aggressive type of lymphoma that represents about 7% of NHL cases. It can be a difficult type of lymphoma to treat. It is found in lymph nodes, the spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal system. Mantle cell lymphoma usually develops in men over age 60 years.

Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL)

SLL is an indolent type of lymphoma that is closely related to B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). It accounts for about 5% of NHL cases.

Marginal Zone Lymphomas (MZLs)

MZLs are categorized depending on where the lymphoma is located. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas usually involve the gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, lungs, saliva glands, or skin. MALT is often associated with a history of an autoimmune disorder (such as Sjögren syndrome in the salivary glands or Hashimoto's thyroiditis in the thyroid gland). MALT is also associated with a bacterial infection in the stomach (H pylori) and can be potentially cured by antibiotics when treated in its early stages. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma affects the spleen, blood, and bone marrow. Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is a rare type of indolent lymphoma that involves the lymph nodes.

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, also called Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia or immunocytoma, is a rare type of lymphoma accounting for about 1% of NHL cases. It usually affects older adults and most often involves bone marrow, lymph nodes, and spleen.

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

This lymphoma affects the brain and spinal cord. Although it is generally rare, it is more common in people who have AIDS.

Burkitt's Lymphoma

Burkitt's lymphoma is one of the most common types of childhood NHL, accounting for about 40% of NHL pediatric cases in the United States. It usually starts in the abdomen and spreads to other organs, including the brain. A specific type of Burkitt's lymphoma that typically occurs in African children often involves facial bones and is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection.

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

This lymphoma is more common in children, accounting for about 25% of NHL pediatric cases, most often boys. It is associated with a large mediastinal mass (occurring in the chest cavity between the lungs) and carries a high risk for spreading to bone marrow, the brain, and other lymph nodes.

Risk Factors

NHL accounts for about 4% of all cancers in the United States. Each year, over 70,000 Americans are diagnosed with NHLs, and an estimated 20,000 people die of the disease. Since the 1970s, NHL incidence rates have doubled. Part of the reason for this dramatic rise may be due to AIDS, which increases the risk for aggressive lymphomas.

The cause of NHL is unknown, but certain factors may increase a person's risk of developing this cancer.

Age

NHL can develop in people of all ages, including children, but it is most common in adults. The most common types of NHL usually appear in people in their 60s and 70s.

Gender

NHL is more common in men than women. In the United States, NHL is the sixth most common cancer in men, and the seventh most common cancer in women.

Race

Overall, the risk for NHL is slightly higher in Caucasians than in African-Americans and Asian Americans.

Family History

People who have close family relatives with a history of NHL may be at increased risk for this cancer. However, no definitive hereditary or genetic link has been established.

Infections

Viral or bacterial infections may play a role in some lymphomas. These include:

- EBV, the cause of mononucleosis, is highly associated with one type of Burkitt's lymphoma and with NHLs linked to immunodeficiency diseases. It is also a risk factor for Hodgkin disease.

- The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS, increases the risk for Burkitt's lymphoma and DLBCL.

- The hepatitis C virus (HCV) may increase the risk for certain types of lymphomas.

- The Helicobacter pylori bacterium, which causes stomach ulcers, is associated with increased risk for MALT lymphomas. (The use of antibiotics to get rid of the bacteria may cause remission in some people who have early-stage MALT lymphoma.)

Immune System Deficiency Disorders

People with diseases or conditions that affect the immune system may be at higher risk for lymphomas:

- HIV-positive patients and those with full-blown AIDS are at higher risk for NHL, and the disease is more likely to be widespread in these people than in those without it. Most AIDS-related NHLs are high-grade lymphomas.

- People who have organ transplants are at higher risk for NHL, probably due to multiple factors, including the drugs used to suppress the immune system and the transplanted organ itself.

- People who have had high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell transplantation are at higher risk.

Autoimmune Disorders

People with a history of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Crohn disease, and Sjögren syndrome, are at an increased risk for certain NHLs, such as MZLs.

Chemical Exposure

Overexposure to a number of industrial and agricultural chemicals (such as pesticides, herbicides, and petrochemicals) has been linked to an increased risk for lymphomas. The data, however, are not consistent.

Researchers are investigating whether some chemotherapy drugs may increase the risk for later developing NHL. At this point, it is not clear whether it is these drugs or the other cancers themselves that increase risk. Other types of drugs, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors that are used to treat autoimmune disorders, are also being studied as possible risk factors for lymphomas.

Radiation Exposure

People who have had radiation treatment for cancers such as Hodgkin's disease appear to have an increased risk for later developing NHLs. The risk may be higher for people treated with both chemotherapy and radiation.

Survivors of nuclear reactor disasters have an increased risk of developing NHL, as well as other types of cancers.

Lifestyle Factors

Lifestyle does not seem to be a major risk factor for NHL. Some studies have suggested that obesity may increase risk, but this association is not definite. Other studies have investigated the role of diet. Although some research has indicated an increased risk for diets high in consumption of red meat and lower risk for diets high in vegetables, the association remains speculative. There is no evidence that smoking increases the risk for NHL itself, although it has been linked with high-grade and follicular NHLs in people with lymphoma.

Symptoms

The most common first sign of lymphoma is a painless enlargement of one or more lymph nodes, usually in the neck, armpits, or groin. These enlarged lymph nodes may cause discomfort depending on where they are located. For example, abdominal tumors may cause stomach distention or pain, while lymph nodes in the chest may cause coughing or difficulty breathing. People should see their doctors if these symptoms do not go away within 2 to 3 weeks.

Sometimes people with NHL do not experience any symptoms, or symptoms may not appear until the cancer is very advanced. Enlarged lymph nodes can also be caused by many noncancerous conditions, such as infections.

Neck lump

The most frequently seen lumps or swellings in the neck are enlarged lymph nodes. This can be caused by bacterial or viral infections, malignancy, and other rare causes.

The most common lumps or swellings in the neck are enlarged lymph nodes. They can be caused by bacterial or viral infections, cancer, and other rare causes.

Systemic and B Symptoms

Lymphomas sometimes cause systemic symptoms -- symptoms that affect the whole body, rather than a specific location. Some systemic generalized symptoms are referred to as B symptoms. People who have B symptoms have a more severe condition than asymptomatic people with the same cancer stage or tumor location or size.

B systemic symptoms include:

- Drenching night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever

Diagnosis

The health care provider will first ask questions about the person's medical history and perform a physical examination to detect any node enlargements. If these procedures indicate lymphoma, additional tests will be done to rule out other diseases or to confirm the diagnosis and extent of the lymphoma.

Physical Examination

The doctor will examine not only the affected lymph nodes but also the surrounding tissues and other lymph node areas for signs of infection, skin injuries, or tumors. The consistency of the node sometimes indicates certain conditions. For example, a stony, hard node is often a sign of cancer, usually one that has metastasized (spread to another part of the body). A firm, rubbery node may indicate lymphoma. Soft tender nodes suggest infection or inflammatory conditions.

Biopsy

A biopsy is the most important test for diagnosing NHL and determining the subtype. Tissue samples retrieved from a biopsy are examined under a microscope to find out if the cell type involved indicates Hodgkin lymphoma or NHL. (Hodgkin lymphoma is marked by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells, which are not found in NHLs.) A biopsy can also help determine the type of NHL and exclude other diagnoses. Sometimes a provider may choose to wait and observe the involved lymph nodes, which will usually go away on their own if a temporary infection is causing the swelling. (However, some lymphomas may go away and appear to be benign, only to reappear at a later time.)

The Procedure

The type of biopsy performed depends in part on the location and accessibility of the lymph node. The doctor may surgically remove the entire lymph node (excisional biopsy) or a small part of it (incisional biopsy). In some cases, the doctor may use fine needle aspiration to withdraw a small amount of tissue from the lymph node.

Results

Even if the biopsy appears normal, in some cases the disease may still be present. The provider should continue to observe the patient until swelling or other signs of disease are gone. Biopsied tissue samples should be frozen in case special tests are later required. These tests are used to detect specific antibodies, genetic and immune factors, and certain markers (substances that may indicate disease) located on the surface of the cells. If lymphoma has been diagnosed, the tissue will be examined for its histology, the cellular structures that determine the lymphoma type.

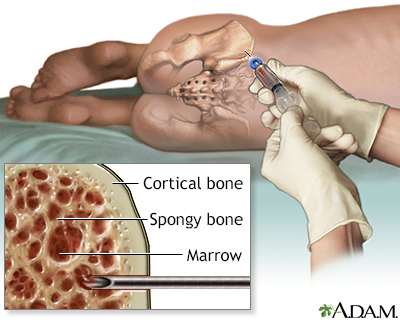

Bone Marrow Aspirate and Biopsy

Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are routinely performed to determine whether the disease has spread. With bone marrow aspirate, bone marrow cells are sucked out through a special needle. A biopsy may be performed before or after the aspiration. In this procedure, a special needle removes a core of the marrow that is structurally intact.

Bone marrow aspiration

A small amount of bone marrow is removed during a bone marrow aspiration. The procedure is uncomfortable, but can be tolerated by both children and adults. The marrow can be studied to determine the cause of anemia, the presence of leukemia or other malignancy, or the presence of some storage diseases, in which abnormal metabolic products are stored in certain bone marrow cells.

Imaging Techniques

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT scans can detect abnormalities in the chest and neck area, as well as revealing the extent of the cancer and whether it has spread. CT scans are used to evaluate symptoms and help diagnose lymphomas, help with staging of the disease, monitor response to treatment, and evaluate symptoms. A CT scan is also often used to detect lymphomas in the abdominal and pelvic areas, the brain, and the chest.

CT scan

CT stands for computerized tomography. In this procedure, a thin X-ray beam is rotated around the area of the body to be visualized. Using very complicated mathematical processes called algorithms, the computer is able to generate a 3-D image of a section through the body. CT scans are very detailed and provide excellent information for the physician.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRIs may be used to detect the spread of the disease to the brain, spine, chest, pelvis, and abdomen.

MRI scans

MRI stands for magnetic resonance imaging. It allows imaging of the interior of the body without using x-rays or other types of ionizing radiation. An MRI scan is capable of showing fine detail of different tissues.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

PET scans can help predict whether an enlarged lymph node is benign or cancerous. PET scans are more accurate than CT scans or other imaging tests for staging lymphomas. PET scans may also help providers determine how well a person has responded to treatment, if any residual cancer exists, and if a person has achieved remission.

Blood Tests

Blood tests help rule out infection and other diseases. Such tests include a complete blood count to measure the number of white blood cells. In a person already diagnosed with lymphoma, blood tests that measure the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are important in determining the prognosis of people with fast-growing lymphomas. High levels indicate bulkier tumors.

Molecular Diagnostic Tests

Tests of lymphoma's DNA are in use or are being developed to detect particular gene defects that help determine prognosis, selection of treatment, and response to treatment. Examples of such abnormal genetic arrangements are those that affect normal cell death, resist chemotherapy, or trigger aggressive cancer growth.

Prognosis

Survival rates for NHL vary widely, depending on the lymphoma type, stage, age of the person, and other variables. According to the American Cancer Society, the overall 5-year relative survival rate for people with NHL is 68% and the 10-year relative survival rate is 57%. (The relative survival rate estimates the likelihood that a person will survive a certain number of years after diagnosis. It is calculated excluding the likelihood of death from diseases other than the cancer.)

Because so many different factors affect survival, it is difficult to make general statements about prognosis. For example, people with very slow growing (indolent) lymphomas can live many years. However, they are usually diagnosed at a late stage, after the cancer has spread, which gives a poorer outlook. Without treatment, aggressive lymphomas are more likely to cause early death, but they are also often curable. In fact, aggressive lymphomas usually have better chances for cure than indolent lymphomas.

Survival rates for people with all types of NHL have greatly improved since the early 1990s, particularly for people under age 45 years. Advances in treatment have contributed to this improvement.

Outlook for Indolent Lymphomas

FLs, the most common indolent (slow-growing) NHLs, are potentially curable in early stages I and II. Unfortunately, these slow-growing malignancies may not produce symptoms until they are in advanced stages. In most cases, these lymphomas are not diagnosed until they have spread to other sites, including the spleen and bone marrow. In such cases, they are difficult to cure. Predicting outcome for indolent FLs is more difficult than for aggressive lymphomas. Even if treatment achieves a response, these tumors almost always recur. Even after relapse, however, the tumors can be treated again if they are still very slow growing.

In general, the average survival rate for FL is 7 to 10 years after diagnosis, depending on other risk factors. New drug treatments, particularly monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), have significantly improved survival rates.

Outlook for Aggressive Lymphomas

High-grade aggressive lymphomas are often symptomatic early on and are potentially curable with aggressive treatments. DLBLC, the most common aggressive NHLs, while fatal if not treated, is often curable with intensive chemotherapy combinations. If relapse occurs after chemotherapy, it usually does so within 2 years.

Most other aggressive lymphomas respond to aggressive chemotherapy. Some aggressive lymphomas, such as mantle cell lymphoma, are sometimes less responsive to standard chemotherapy.

International Prognostic Index

Doctors often use a scoring system called the International Prognostic Index for predicting outcome in people with more aggressive B-cell lymphomas such as DLBCL. It uses five risk factors to help predict survival odds:

- Being older than age 60 years -- this age group tends to have other medical conditions, which contribute to the poorer prognosis

- Having a disseminated tumor (stage III or IV)

- Disease that has spread to more than one site beyond the lymph nodes

- The person's functional ability

- Having elevated blood levels of the LDH protein

Having one or none of these risk factors indicates the best outlook. Two factors indicate a low-to-intermediate likelihood of a poor outlook. Three factors predict an intermediate-to-high likelihood of poor outlooks. Finally, 4 or 5 factors pose the highest likelihood of poor survival. However, the International Prognostic Index was developed before the introduction of newer drug therapies like rituximab, which has dramatically improved the outcome of people with DLBCL. A newer version of the index has been developed since the use of rituximab became more widespread.

A similar prognostic index is used for FL.

Long-Term Complications of Treatments

The radiation and chemotherapy treatments used for treating NHL can potentially have long-term effects on many organs in the body and can increase the risk for serious illnesses, including heart disease and certain cancers. Other long-term effects of cancer treatments include somatic symptoms such as fatigue and generalized aches and pains.

Some cancer treatments can cause infertility. People who may wish to have children in the future should ask their providers about fertility-preserving treatments. It is very important to have these discussions before cancer treatment starts. The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has guidelines for the best fertility preservation methods for male and female cancer people. They include sperm freezing and banking (sperm cryopreservation) for men, and egg (oocyte) and embryo cryopreservation for women.

Treatment

Treatment for NHL is highly specific for each person and is determined by the tumor classification. It includes the following factors:

- Stage (the extent of the tumor)

- Grade (the growth pattern of the tumor)

- Histologic type (cellular structure)

- Location of tumor

- Molecular characteristics of the cells

- Other factors, such as blood levels of LDH or person's age and overall health status

Staging and Grading

Grading refers to how fast the tumor cells grow and divide, and for how fast the tumor itself spreads. In NHL, indolent lymphomas are slow growing and referred to as low grade. Aggressive lymphomas are fast growing and referred to as high grade. Aggressive lymphomas are considered more curable than indolent lymphomas. Indolent lymphomas may respond to treatment but tend to recur. (Recurrence is also called relapse.)

Staging refers to where the tumor is contained and where it has spread. The stages of NHL are:

Stage I. In Stage I (early disease), lymphoma is found in only one lymph node area or in only one area or organ outside the lymph nodes.

Stage II. In Stage II (locally advanced disease), lymphoma is found in two or more lymph nodes on the same side of the diaphragm or the lymphoma extends from a single lymph node or a single group of lymph nodes into a nearby organ.

Stage III. In Stage III (advanced disease), lymphoma is found in lymph node areas above and below the diaphragm. Lymphoma may have also spread into areas or organs adjacent to lymph nodes, such as the spleen.

Stage IV. In Stage IV (widespread disease), the lymphoma has spread (metastasized) via the bloodstream to organs outside the lymph system, such as the bone marrow, brain, skin, or liver.

Treatment Options

The main treatments for NHL are:

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Biologic therapy (immunotherapy) with MAbs and modified T-cells (CAR-T)

- Targeted therapy

- Stem cell or bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

In the early stages of lymphoma, providers may recommend watchful waiting where treatment is delayed until symptoms appear or worsen. Treatment for lymphomas generally uses chemotherapy (particularly intensive regimens using several drugs) or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation. Monoclonal antibody biologic drugs, which are now being used more frequently in combination with chemotherapy drugs, were the first type of immunotherapy. A more recent immunotherapy approach called CAR-T involves the person's own T-cells genetically modified to attack cancer cells. Transplantation is mainly used to treat people who relapse. Surgery is not a usual treatment option.

People may also wish to consider enrolling in a clinical trial that tests new and experimental drugs or treatments.

Assessing Treatment Success

In assessing the success of a clinical trial, doctors often refer to the tumor response. A complete response, for example, means that there is no longer any evidence of the disease by examination, blood tests, or x-ray studies. It does not necessarily mean that the disease is cured. It may still recur later on.

Imaging such as CT scans, MRI scans, or a PET may be done after a course of chemotherapy. At times, a PET scan may be done after just 1 to 3 cycles of chemotherapy (but before the full course of chemotherapy is completed) to assess if it appears there is a response. A change in the chemotherapy regimen may be instituted if it does not appear the tumor is improving after the PET scan.

In judging the success of a treatment for NHL, the most important criteria are overall survival and the duration of time until the disease progresses or the person dies.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy plays a role in the treatment of nearly all people with lymphoma and has achieved remarkable results, even in late stages. It uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Such drugs are called cytotoxic drugs. Chemotherapy is referred to as systemic therapy because the drugs travel throughout the bloodstream to the entire body.

Chemotherapy may also be used along with radiation.

Chemotherapy Administration

A chemotherapy cycle is usually 21 to 28 days. People take the drugs for a few days, then have a period of rest. The drugs may be taken as pills at home or given by injection or infusion in a medical center or doctor's office. Chemotherapy is injected into the spinal fluid if the cancer has spread to the brain. This approach is called intrathecal chemotherapy. Intrathecal chemotherapy is also used as a preventive measure in people at high risk for central nervous system involvement. Some people receiving chemotherapy need to remain in the hospital for several days so the effects of the drug can be monitored.

Effective Regimens and Drugs

CHOP

A current standard chemotherapy regimen for NHL is CHOP. CHOP is a combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (Adriamycin), vincristine (Oncovin), and prednisone. It is particularly effective for many stages of lymphoma when used in combination with rituximab (Rituxan), a biologic drug. (See Biologic Therapy section of this report.) Some studies of this combination in low-grade lymphomas have reported response rates of 70% to 100%.

Bendamustine

Bendamustine (Treanda, Bendeka) has replaced CHOP in the management of low grade lymphomas. It is often used in combination with rituximab (combination called BR).

Fludarabine

Fludarabine (Fludara) is a type of drug called a nucleoside analogue. It is one of the most used drugs for treating low-grade lymphomas. Fludarabine is often used in a chemotherapy regimen called FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab). Other fludarabine regimens for follicular and low-grade lymphomas are FAD (fludarabine, adriamycin, and dexamethasone) and FND (fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone).

Etoposide

Etoposide is another cancer drug that is sometimes used in a regimen called EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin.) EPOCH may be used in combination with rituximab.

Side Effects and Complications

Side effects and complications of any chemotherapeutic regimen are common. They are more severe with higher doses. Side effects may increase over the course of treatment. Radiation treatment may worsen chemotherapy side effects.

Common Side Effects

Common side effects include:

- Nausea and vomiting. Drugs known as serotonin antagonists, such as ondansetron (Zofran) or granisetron (Kytril), can relieve these side effects.

- Diarrhea.

- Hair loss.

- Mouth sores.

- Weight loss.

- Depression.

These side effects are nearly always temporary. Most people are able to continue with normal activities for all but perhaps a few days a month.

Serious Side Effects

Serious chemotherapy side effects can also occur and may vary depending on the specific drugs used. They include:

- Neutropenia a severe drop in the number of white blood cells produced in the bone marrow. Neutropenia increases the chance for infection and is a potentially life-threatening condition. Drugs called granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) are used to help boost white blood cell count. These drugs, which include filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta), can help lessen the risk for neutropenia occurrence and, if neutropenia does occur, to reduce its length and severity. People should also use lifestyle precautions to prevent infection. (See Transplantation section of this report.)

- Anemia, a lack of red blood cells. Erythropoietin stimulates red blood cell (hemoglobin) production and can help reduce or prevent this side effect. It is available as epoetin alfa (Epogen, Procrit) and darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp). In people with cancer, these drugs should be used to treat only severe anemia associated with chemotherapy and to maintain hemoglobin levels at 10 g/dL. Treatment should stop as soon as chemotherapy is complete. These drugs may not be safe or appropriate for all people.

- Liver and kidney damage.

- Abnormal blood clotting (thrombocytopenia).

- Allergic reaction.

Long-Term Complications

- Fatigue is very common after chemotherapy and may last for several years.

- Bladder cancer is associated with certain types of chemotherapy drugs used for NHL.

- Infertility is a risk, particularly with the use of cyclophosphamide.

- Heart failure risk increases with regimens containing certain drugs, particularly doxorubicin or mitoxantrone.

- Osteoporosis (bone thinning) and increased risk for fracture may occur in people treated with steroid drugs such as prednisone.

In general, these serious late side effects depend on the type of drug used and cumulative drug dose.

Biologic Therapy (Immunotherapy)

Biological response modifier therapy, also called immunotherapy, uses the body's own immune system to fight cancer. These biologic drugs are often combined with other treatments.

MAbs are the main drugs used in biologic therapy. MAbs are designed in the laboratory to mimic the body's natural antibodies and attack specific antigens (foreign substances) produced by the cancer. Lymphomas carry antigens that provoke strong immune responses and so are particularly good candidates for MAb therapy.

CAR-T is a newer type of immunotherapy, also called adoptive cell transfer, which uses the patient's own T-cells as drugs targeting cancerous B-cells.

Rituximab

Rituximab (Rituxan) was the first monoclonal antibody approved for cancer. This drug targets the CD-20 antigen, which is found on most B-cell lymphomas. It is the most commonly used biologic drug, particularly in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens.

Rituximab is used to treat many types of CD20-positive tumors. Rituximab is used as a single drug or in combination with chemotherapy for low-grade or FL. It is also used in combination with other drugs for other types and stages of lymphomas including diffuse large B-cell (DLBC). Rituximab in combination with CHOP (a regimen called R-CHOP, or CHOP-R) is used for first-line treatment of aggressive lymphomas. Rituximab may also be combined with bendamustine and polatuzumab (Polivy) (polatuzumab vedotin-piiq) to treat patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) that has progressed or returned after at least two prior therapies.

Rituximab is given by infusion. The treatment has mild-to-moderate short-term side effects, including nausea, fever, chills, hives, dizziness, and headache. Uncommon and more serious side effects are severe allergic reactions, very low blood pressure, blood abnormalities, wheezing, infections, and sudden heart events.

Rituximab has also been associated with cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare and potentially deadly brain disorder. People who experience any of the following symptoms should immediately contact their providers:

- Vision problems or unusual eye movements

- Confusion

- Dizziness or loss of balance

- Difficulty talking or walking

People who have previously had hepatitis B, or who are at high-risk for this viral infection, should be tested before taking rituximab because the drug has been linked to reactivation of the hepatitis B virus. People who are HIV-positive may experience more adverse effects from rituximab than with CHOP alone.

Radioimmunotherapies

Some newer MAbs are used to treat NHL by attaching radioactive molecules to them. When the drug is injected, the monoclonal antibody targets an antigen (protein) on the surface of the tumor. The radioisotope is then delivered directly into the tumor where it kills the cancer. Ibritumomab targets the CD-20 antigen. Treatment takes about 7 to 9 days to complete, compared to several months for traditional chemotherapy treatments.

- Ibritumomab (Zevalin) is approved for patients with relapsed or refractory low-grade, follicular or transformed B-cell NHL, and for patients with follicular NHL who have not responded to rituximab (Rituxan). It has been safely used for patients with advanced NHL who have had stem cell transplantation.

In general, these drugs cause fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy. However, serious complications may include skin infections, severe allergic reactions, and temporary lowering of blood counts. Due to the radioisotope component, these drugs are also more difficult to administer than rituximab. They tend to be used if people do not respond to rituximab.

CAR-T cell therapy

CAR-T cell therapy has recently become available as a treatment option for certain types of NHL. CAR-T involves using the body's own T-cells.

- These cells are separated from a sample of the person's blood and genetically modified. As a result, they express a specific receptor (chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR).

- This receptor recognizes a matching molecule on the cancerous B-cells.

- These CAR-T cells are then multiplied and infused back into the person where they target and kill the cancerous cells.

The CAR-T cell approaches currently in use for NHL are:

- Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta)

- Isagenlecleucel (Kymriah)

- Brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus)

All of these therapies target the CD19 antigen and are approved to treat certain types of B-cell NHL. These include DLBCL, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade NHL, and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). People whose disease relapsed or did not improve after at least two other types of treatments may receive these new treatments.

Serious side effects are possible following CAR-T cell therapy. These include high fever, low blood pressure, as well as toxic effects on the brain, and serious infections resulted from a weakened immune system.

Due to the promising results obtained so far, the CAR-T therapy field is rapidly evolving and more adoptive cell transfer treatment strategies are expected in the near future.

Other Targeted and Biologic Drugs

Three biologic drugs are FDA-approved for treatment of mantle cell lymphoma:

- Bortezomib (Velcade) is a proteasome inhibitor drug. It is approved for use in mantle cell lymphoma.

- Lenalidomide (Revlimid) is the first and only oral therapy for mantle cell lymphoma. It was approved for people whose disease has relapsed or progressed after two prior therapies, one of which included bortezomib. Lenalidomide is chemically related to thalidomide, a drug which can cause severe birth defects. Lenalidomde is also used in the treatment of other forms of NHL.

- Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) targets B-cell machinery. It is approved for use in several types of NHL.

- Selinexor (Xpovio) is the first in a new class of drugs that works by inhibiting nuclear export, the process by which proteins travel from the nucleus to the cystoplasm of a cell. Selinexor was recently approved for people with relapsed or refractory diffuse B-cell lymphoma and is currently under investigation for use in several other cancers.

- Tazemetostat (Tazverik) is an inhibitor of a molecule called EZH2. This drug is approved for treatment of people with follicular lymphoma whose tumors test positive for a mutation in EZH2.

- Tafasitamab-cxix (Monjuvi) is another drug that targets CD-19. Given in combination with lenalidomide, tafasitamab-cxix was approved for diffuse B-cell lymphoma in people whose disease has relapsed or has not responded to other therapies and who are not eligible for stem cell transplantation.

Radiation

Radiation therapy uses high energy x-rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. It may also be used as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms in advanced cancer. Radiation may be used as the sole therapy for some early-stage (I or II) lymphomas, or may be used along with chemotherapy for later-stage (III or IV) lymphomas.

Radiation is tailored to the individual and usually limited to the diseased areas and possibly nearby regions:

- If the lymphoma is confined to tissues above the diaphragm, radiation may be delivered to the neck, chest, and under arms (called the mantle field) and sometimes to lymph nodes in the upper abdomen or spleen or both.

- If the lymphoma is below the diaphragm, subtotal nodal radiation may be used, which is directed to other regions, including lymph nodes in the upper abdomen, spleen, and pelvis, in addition to the mantle-field.

- Radiation to the brain is called cranial radiation.

- Radiation to all the lymph nodes in the body is called total nodal radiation.

- Involved site radiation is given just to the lymph nodes involved with lymphoma.

- Total body irradiation may sometimes be performed before stem cell transplant to eliminate any remaining cancer cells that were not destroyed by chemotherapy.

Side Effects and Complications

Fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, dry mouth, skin irritation, and increased risk for infections are common short-term side effects of radiation therapy. These side effects generally clear up after treatment is completed.

Radiation therapy can cause more serious long-term complications. These side effects generally depend on the radiation target site in the body. They include:

- Chest radiation can lead to lung damage and difficulty breathing. Chest radiation may also increase the long-term risk for heart disease, heart attack, and lung cancer. Although rare, the development of breast cancer is a particular concern for young women and adolescent girls treated with chest radiation.

- Neck radiation may increase the later risk for underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) and thyroid cancer.

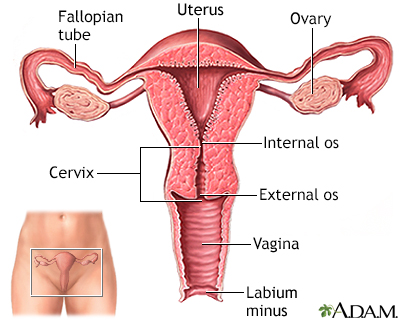

- Radiation to the pelvic area may increase the risk for infertility, particularly for women. A procedure called ovarian transposition may be used to surgically move the ovaries away from the path of radiation.

Lungs

The major features of the lungs include the bronchi, the bronchioles and the alveoli. The alveoli are the microscopic blood vessel-lined sacks in which oxygen and carbon dioxide gas are exchanged.

Uterus

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ located in the female pelvis between the bladder and rectum. The ovaries produce the eggs that travel through the fallopian tubes. Once the egg has left the ovary it can be fertilized and implant itself in the lining of the uterus. The main function of the uterus is to nourish the developing fetus prior to birth.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is a decreased activity of the thyroid gland which may affect all body functions. The rate of metabolism slows causing mental and physical sluggishness. The most severe form of hypothyroidism is myxedema, which is a medical emergency.

Transplantation

Stem cell transplantation involves removing and replacing stem cells, which are produced in the bone marrow. Stem cells are the early forms for all blood cells in the body. Transplantation is usually reserved for people with relapsed aggressive NHL or people whose lymphoma is in remission but is likely to return.

Stem cell transplantation usually follows an intensive regimen of high-dose chemotherapy, which is sometimes given along with radiation. The goal of the high-dose chemotherapy is to destroy as many cancer cells as possible, including cancer cells that have been resistant to standard-dose treatment. However, high-dose chemotherapy also destroys bone marrow and the stem cells it contains. Transplantation allows for the reintroduction of healthy blood-forming stem cells.

Collecting the Stem Cells

Sources of Cells

Stem cells must first be collected in one of the following ways:

- Directly from blood, called peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT)

- From bone marrow, called BMT

- From umbilical cords or placentas

PBSCT is the most commonly performed type of stem cell transplantation.

Donor or Patient Cells

The marrow or blood stem cells can be taken from the patient (autologous) or from a matched donor (allogeneic):

- In an autologous transplant, the marrow or blood cells used for replacement are taken from the patient. Autologous transplants are the most common type of transplant used for lymphoma. However, if the cancer has spread to the blood or bone marrow, there is some danger that these cells may contain tumor cells, and that the cancer can regrow.

- In an allogeneic transplant, bone marrow or stem cells are taken from a donor. Siblings are the best donors. Only about 25% of transplants for NHL are the allogeneic type. Allogeneic transplants have increased risks for serious side effects and complications. Older people who cannot tolerate the preparatory treatment required for a standard allogeneic transplant may be able to receive a non-myeloablative transplant ("mini-transplant"), which uses lower doses of chemotherapy and radiation.

The Blood Stem Cell Collection Procedure

With PBSCT:

- The donor is usually given a drug called granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, or G-CSF (filgrastim, lenograstim, pegfilgrastim) to stimulate stem cell growth.

- The person (or donor in an allogeneic procedure) then undergoes apheresis. With this process the blood is withdrawn from one of the person's veins, then passes through a machine that filters out the white cells and platelets, which contain the stem cells. The blood is returned through another vein. The entire procedure takes 3 to 4 hours but needs to be repeated several times.

- The stem cells are treated to remove contaminants and then are frozen to keep them alive until the person is ready to receive them.

Formed elements of blood

Blood transports oxygen and nutrients to body tissues and returns waste and carbon dioxide. Blood distributes nearly everything that is carried from one area in the body to another place within the body. For example, blood transports hormones from endocrine organs to their target organs and tissues. Blood helps maintain body temperature and normal pH levels in body tissues. The protective functions of blood include clot formation and the prevention of infection.

Blood transports oxygen and nutrients to body tissues and returns waste and carbon dioxide. Blood also distributes nearly everything that is carried from one area in the body to another place within the body. For instance, blood helps transport hormones from the endocrine organs to their target organs. Blood also helps maintain body temperature. The protective functions of blood include clot formation and the prevention of infection.

The Transplantation Procedure

- Stem cell transplants are preceded by chemotherapy treatment known as conditioning. The goal of this treatment is to inactivate the immune system and to kill any residual malignant cells. It is extremely toxic since it also destroys non-malignant marrow cells.

- A few days after treatment, the person is given the stored stem cells, which are administered through a vein. This may take several hours. People may have a fever, chills, hives, shortness of breath, or a fall in blood pressure during the procedure.

- The person may be treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after chemotherapy. The goal is to stimulate the growth of infection-fighting white blood cells.

- The person is kept in a protected environment to minimize infection. People who have received an allogeneic transplant may need blood cell replacement, nutritional support, and drugs to treat graft-versus host disease. They can usually leave the hospital within 3 to 5 weeks.

Transplantation Side Effects and Complications

Stem-cell transplantation is a serious and complex procedure that can cause many short- and long-term side effects and complications.

Early side effects of transplantation are similar to chemotherapy and include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, mouth sores, and loss of appetite. Bleeding due to reduced platelets is a high risk during the first 4 weeks.

Later side effects include fertility problems (if the ovaries are affected), thyroid gland problems (which can affect metabolism), lung damage (which can cause breathing problems) and bone damage. In younger people, there is a small long-term risk for development of secondary cancers such as leukemia.

Two of the most serious complications of transplantation are infection and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Infection resulting from a weakened immune system is the most common danger. The risk for infection is most critical during the first 6 weeks following the transplant, but it takes 6 to 12 months post-transplant for a person's immune system to recover.

Many people develop severe herpes zoster virus infections (shingles) or have a recurrence of herpes simplex virus infections (cold sores and genital herpes). Pneumonia, and infection with germs that normally do not cause serious infections such as cytomegalovirus, aspergillus (a type of fungus), and Pneumocystis jiroveci (a fungus) are among the most important life-threatening infections.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

GVHD is a serious attack by the person's immune system triggered by the donated new marrow in allogeneic transplants. Mild cases of GVHD can actually be helpful as they can cause graft-versus-lymphoma where the immune system kills remaining lymphoma cells. Still, severe GVHD can pose serious complications.

Acute GVHD occurs in 30% to 50% of allogeneic transplants, usually within 25 days. Its severity ranges from very mild symptoms to a life-threatening condition (more often in older people). The first sign of acute GVHD is a rash, which typically develops on the palms of hands and soles of feet and can then spread to the rest of the body. Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, diarrhea, loss of appetite and jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes). To prevent acute GVHD, doctors give people immune-suppressing drugs such as steroids, methotrexate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and MAbs.

Chronic GVHD can develop 70 to 400 days after the allogeneic transplant. Initial symptoms include those of acute GVHD. Skin, eyes, and mouth can become dry and irritated, and mouth sores may develop. Chronic GVHD can also sometimes affect the esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, and liver. Bacterial infections and chronic low-grade fever are common. Chronic GVHD is treated with similar medicines as acute GVHD.

Too much sun exposure can trigger GVHD. Be sure to always wear sunscreen (SPF 15 or higher) on areas of the skin that are exposed to the sun. Stay in the shade when you go outside.

Avoiding Infection after a Transplant

It is very important to take precautions to avoid infections. Guidelines for post-transplant infection prevention include:

- Discuss with your doctor what vaccinations you need and when you should get them.

- Avoid crowds, particularly during cold and flu season.

- Be diligent about hand washing and make sure that visitors wash their hands. Alcohol-based hand rubs are best.

- Avoid eating raw fruits and vegetables -- food should be well cooked. Do not eat foods purchased at salad bars or buffets. In the first few months after the transplant, be sure to eat protein-rich foods to help restore muscle mass and repair cell damage caused by chemotherapy and radiation.

- Boil tap water before drinking it.

- Dental hygiene is very important, including daily brushing and flossing. Schedule regular visits with your dentist.

- Do not sleep with pets. Avoid contact with pets' excrement.

- Avoid fresh flowers and plants as they may carry mold. Do not garden.

- Swimming may increase exposure to infection. If you swim, do not submerge your face in water. Do not use hot tubs.

- Report to your doctor any symptoms of fever, chills, cough, difficulty breathing, rash or changes in skin, and severe diarrhea or vomiting. Fever is one of the first signs of infection. Some of these symptoms can also indicate graft-versus-host disease.

- Report to your ophthalmologist any signs of eye discharge or changes in vision. People who undergo radiation or who are on long-term steroid therapy have an increased risk for cataracts.

Resources

- National Cancer Institute -- www.cancer.gov

- American Cancer Society -- www.cancer.org

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society -- www.lls.org

- American Society of Clinical Oncology -- www.asco.org

- Lymphoma Research Foundation -- www.lymphoma.org

- ASCO Cancer.Net -- www.cancer.net

- National Cancer Institute: Find clinical trials -- www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials

Reviewed By

Todd Gersten, MD, Hematology/Oncology, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, Wellington, FL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Abramson JS. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 103.

Armitage JO, Gascoyne RD, Lunning MA, Cavalli F. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):298-310. PMID: 28153383 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28153383/.

Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, Version 2.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(7):882-913. PMID:27407129 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27407129/.

Bhattarai M, Rao K. Lymphomas presenting in the head and neck. In: Flint PW, Francis HW, Haughey BH, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 116.

Bierman PJ, Armitage JO. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 176.

Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies for lymphoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(1):31-46. PMID: 28857075 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28857075/.

Ghobadi A. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Res Transl Med. 2018;66(2):43-49. PMID: 29655961 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29655961/.

Hochberg J, Goldman SC, Cairo MS. Lymphoma. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 523.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. NCCN guidelines for patients. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/cancers.aspx#nhl. Accessed September 17, 2020.

Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility Preservation in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1994-2001. PMID: 29620997 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29620997/.

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Adult Non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment (PDQ®): health professional version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-2020 Jun 26. PMID: 26389492 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26389492/.

PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. Childhood Non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment (PDQ®): health professional version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-2020 Aug 7. PMID: 26389181 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26389181/.

Sandlund JT, Onciu M. Childhood lymphoma. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 94.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.