Premenstrual syndrome - InDepth

PMS - InDepth; Premenstrual dysphoric disorder - InDepth; PMDD - InDepthAn in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

Highlights

Premenstrual Syndrome Symptoms

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) can produce physical and emotional or behavioral symptoms in the days before menstruation.

Physical symptoms of PMS may include:

- Breast swelling and tenderness

- Abdominal bloating

- Fluid retention

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Headache and migraine

- Changes in appetite

- Acne

- Muscle and joint pain

- Lethargy and fatigue

Emotional and behavioral symptoms of PMS may include:

- Depression

- Anxiety and tension

- Insomnia or oversleeping

- Change in sexual interest and desire

- Irritability

- Hostility and outbursts of anger

- Mood swings

- Difficulty concentrating

- Crying spells

- Social withdrawal

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Symptoms

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a specific psychiatric condition marked by severe depression, irritability, and tension before menstruation. For a doctor to confirm a diagnosis of PMDD, a woman must have symptoms during the last week of the premenstrual phase and improve within a few days after menstruation starts.

Five or more of the following symptoms must occur:

- Mood swings marked by periods of tearfulness

- Irritability, anger, or interpersonal conflicts

- Increased sensitivity to rejection

- Depressed mood or feelings of hopelessness

- Feelings of tension or anxiety

- Disinterest in daily activities and relationships

- Trouble concentrating

- Fatigue or low energy

- Food cravings or binge eating

- Sleeping too much or too little

- Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

- Physical symptoms, such as breast swelling or tenderness, joint or muscle pain, bloating, or weight gain

Other menstrual disorders include dysmenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, and menorrhagia.

Menstrual disorders

An in-depth report on the causes, treatment, and prevention of menstrual disorders.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Introduction

Premenstrual Syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a set of emotional and physical symptoms that typically occur up to 5 days before a woman starts her monthly menstrual cycle. The symptoms usually stop when menstruation begins, or shortly thereafter.

The menstrual cycle and the function of female reproductive organs are controlled by several hormones secreted in the hypothalamus (GnRH), pituitary gland (FSH and LH) and ovaries (estrogen and progesterone).

A menstrual cycle lasts an average of 28 days, although the cycle length may range from 21 to 34 days and still be considered normal. When a woman reaches her 40s the cycle lengthens, reaching an average of 31 days by age 49.

Ovulation is when an egg is released from the woman's ovary, which occurs mid-way through the menstrual cycle, around day 14 (in a 28-day cycle). A menstrual cycle is associated with hormonal changes and has two main phases, which precede and follow ovulation:

- The follicular (proliferative) phase, which occurs from day 1 (when menstrual bleeding starts) through day 13. At the beginning of the follicular phase, the lining of the uterus (called endometrium) breaks down and sheds during the menstruation. The endometrium then grows for the rest of the follicular phase. A pituitary hormone called follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates maturation of follicles in the ovary.

- The luteal (secretory) phase, which occurs from days 15 to 28. During this phase, the follicle that released the egg forms the corpus luteum, a structure which helps increase levels of progesterone for pregnancy and which degrades if fertilization does not occur.

PMS is associated with the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, after ovulation. Estrogen and progesterone levels rise in the first part of the luteal phase to help prepare the endometrial lining of the uterus for an embryo.

If conception (pregnancy) does not occur, the levels of these hormones decrease in the latter part of the luteal phase, and the lining and unfertilized egg are shed through menstruation in the beginning of the follicular phase. Levels of other types of hormones also rise and fall during the menstrual cycle.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a condition marked by severe depression symptoms, irritability, and tension before menstruation. The symptoms of PMDD are similar to those of PMS, but they are generally more severe and debilitating. Like PMS, symptoms of PMDD occur during the luteal phase in the week before menstrual bleeding begins. Symptoms usually improve within a few days after the period starts.

Typical Menstrual Cycle |

||

|

Menstrual Phases |

Typical No. of Days |

Hormonal Actions |

|

Follicular (Proliferative) Phase |

Cycle Days 1 to 6: Beginning of menstruation to end of blood flow. |

Estrogen and progesterone start out at their lowest levels. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels rise to stimulate maturity of follicles. Ovaries start producing estrogen and levels rise, while progesterone remains low. |

|

Cycle Days 7 to 13: The endometrium (the inner lining of the uterus) thickens to prepare for the egg implantation. |

The endometrium thickens to prepare for the egg implantation. |

|

|

Ovulation |

Cycle Day 14: |

Surge in luteinizing hormone (LH). Largest follicle bursts and releases egg into fallopian tube. |

|

Luteal (Secretory) Phase, also known as the Premenstrual Phase |

Cycle Days 15 to 28: |

Ruptured follicle develops into corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. Progesterone and estrogen stimulate blanket of blood vessels to prepare for egg implantation. |

|

If fertilization occurs: |

Fertilized egg attaches to blanket of blood vessels that supplies nutrients for the developing placenta. Corpus luteum continues to produce estrogen and progesterone. |

|

|

If fertilization does not occur: |

Corpus luteum deteriorates. Estrogen and progesterone levels drop. The blood vessel lining sloughs off and menstruation begins. |

|

Menstrual Cycle Tool

Causes

Doctors do not know exactly what causes PMS. Fluctuations in female reproductive hormones (progesterone or estrogen) and brain chemicals may play a role although their exact significance is unclear. Hormonal levels seem to be the same in women whether or not they have PMS. It is possible that women with PMS are somehow more sensitive to these changing levels of hormones.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal System

Disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system may be involved with PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). The HPA system controls reproduction, appetite, and feelings of well-being, and is also involved in regulating the stress response. A number of hormones and neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) play important and complicated interrelated roles in the activity of the HPA system:

- Reproductive hormones. The two important female hormones, progesterone and estrogen, are at their highest levels during the premenstrual period. PMS may be more strongly related to an abnormal response to progesterone than estrogen.

- Neurotransmitters. Each hormone is involved in the regulation of two neurotransmitters, serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). These brain chemicals have properties that may protect against PMS symptoms. Serotonin helps regulate mood and behavior. GABA has an effect on calmness and anxiety.

- Stress hormones. Stress hormones include cortisol and norepinephrine.

While hormonal and brain chemical changes certainly play a role, it is not exactly clear how they cause PMS or PMDD. Cyclic fluctuations in some of these hormones, and not whether their levels are high or low, may be the important factors in premenstrual problems.

Risk Factors

Many women in their reproductive years experience some of the emotional and physical symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). A small percentage of women report very severe symptoms, notably premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). A number of factors may put a woman at higher risk for PMS.

Age

PMS tends to occur in women who are in their late 20s to early 40s. Symptoms usually begin when a woman is in her mid-twenties. PMS and other menstrual problems end at menopause when a woman stops having menstrual periods.

Family History

A woman whose mother had PMS is more likely to have PMS herself. There is limited evidence suggesting that there may also be a genetic component for PMDD.

Pregnancy History

Some studies showed that nulliparity (never having given birth) is associated with PMS.

Psychological Factors

Women with past or current mood or anxiety disorders, including depression, may be at increased risk for PMS and PMDD. A history of postpartum depression is a risk factor as is history of alcohol abuse.

Lifestyle Factors

Poor eating habits may contribute to PMS. Dietary issues associated with PMS include:

- Not getting enough minerals and vitamins in your diet. Deficiencies in calcium and B vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin) may be associated with PMS.

- Eating too much salty food. This can cause bloating and fluid retention.

- Drinking too much alcohol and too many caffeinated beverages. Alcohol worsens PMS symptoms and may increase the risk for prolonged cramping (dysmenorrhea) during menstruation.

Stress does not cause PMS, but it may worsen symptoms. Exercise can help reduce stress and boost energy levels.

Complications

Risk for Major Depression

Depression and PMS often coincide, and may in some cases be due to common factors. Some studies suggest that PMDD may increase the risk of depression after giving birth (postpartum) or during the transition to menopause (perimenopause).

Magnification of Other Medical Conditions

A number of conditions worsen during the premenstrual or menstrual phase of the cycle, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as menstrual magnification.

Migraines

About half of women with migraines report an association with menstruation, usually in the first days before or after menstruation begins. Compared to migraines that occur at other times of the month, menstrual migraines are often more severe, last longer, and do not have auras.

Asthma

Asthma attacks often increase or worsen during the premenstrual period.

Other Disorders

Many other chronic medical conditions may be exacerbated during the premenstrual phase, including epilepsy and other seizure disorders, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, irritable bowel syndrome, and inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn and ulcerative colitis.

Symptoms

PMS is a set of physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms that occur during the last week of the luteal phase (1 to 2 weeks before menstruation). The symptoms typically start in the 5 days before menstruation begins and go away within 4 days after bleeding starts. Symptoms do not start again until at least day 13 in the cycle.

Once established, the symptoms tend to remain fairly constant until menopause, although they can vary from cycle to cycle.

Physical Symptoms

- Fluid retention, which can cause abdominal bloating and weight gain

- Breast swelling and tenderness

- Increased appetite, often with specific food cravings (especially salt and sugar)

- Gastrointestinal problems (stomach cramps, diarrhea, and constipation)

- Skin problems (acne)

- Headache and migraine (migraine may increase severity of PMS symptoms)

- Muscle and joint aches or pains

- Lethargy, fatigue, and lack of energy

Emotional and Behavioral Symptoms

- Depression

- Anxiety and tension

- Insomnia or oversleeping

- Change in sexual interest and desire (although some women lose interest, others have a heightened drive)

- Irritability

- Hostility and outbursts of anger

- Mood swings

- Social withdrawal

- Crying spells

- Poor concentration

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

The American Psychiatric Association has specific criteria that define premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD is a condition marked by severe depression, irritability, and tension before menstruation. PMDD has features of both anxiety and depression disorders.

PMDD Diagnostic Criteria

Symptoms must occur during the last week of the premenstrual (luteal) phase in most menstrual cycles. They should improve within a few days after the period starts. Symptoms should be absent by the end of the first menstrual week. They should markedly interfere with work or social functioning. Also, symptoms should be clearly related to the menstrual cycle and not just be those of another underlying disorder.

Five or more of the following symptoms must occur:

- Mood swings marked by periods of tearfulness

- Irritability, anger, interpersonal conflicts

- Increased sensitivity to rejection

- Depressed mood or feelings of hopelessness

- Feelings of tension or anxiety

- Disinterest in daily activities and relationships

- Trouble concentrating

- Fatigue or low energy

- Food cravings or binge eating

- Sleep problems (sleeping too much or too little)

- Feelings of being overwhelmed or out of control

- Physical symptoms, such as breast swelling or tenderness, joint or muscle pain, bloating, or weight gain

Diagnosis

Your health care provider will ask about your symptoms and may ask you to fill out a questionnaire. The best method for determining your PMS patterns is to track your symptoms in a personal diary for 2 to 3 months:

- Divide symptoms into physical (bloating, headaches, weight gain, aches and pains, breast tenderness, fatigue, and lack of energy) and emotional and mental (depression, anger, and changes in sexual drive). Note: Menstrual cramps are NOT part of PMS.

- Begin recording symptoms on day 1 of the cycle, which is the day bleeding begins.

- Be sure to record your symptoms in each category every day. This is an important diagnostic tool. This record keeping will also help you understand how certain conditions or activities may increase or lessen the effects of PMS.

- Record symptom severity using an index from 1 to 4, with 1 being no symptoms and 4 being the most severe.

- Include any medications taken or events that might contribute to emotional or physical responses.

Ruling Out Other Conditions

If the symptoms consistently resolve once menstruation begins, they are most likely caused by hormonal fluctuations. If they persist or do not appear to be associated with a regular cycle, other conditions may be causing them. Among the possible conditions that mimic some PMS symptoms are:

- Psychiatric disorders (depression or anxiety that persists suggests serious mood disorders that are unrelated to PMS)

- Eating disorders

- Anemia

- Thyroid disorders

- Diabetes

- Endometriosis

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Side effects of oral contraceptives

- Perimenopausal symptoms in women over age 40 (these can include breast tenderness, headaches, sleep disturbances, and mood swings)

Treatment

For many women, PMS symptoms can be relieved by lifestyle changes (food modifications, exercise, and possibly vitamin B-6 and calcium supplements).

Women with more severe PMS whose symptoms have not been helped by lifestyle changes should discuss drug treatment options with their doctors. Medications for PMS include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to help reduce pain.

- Diuretics to reduce fluid retention.

- Birth control pills to help improve symptoms, such as breast pain, bloating, and acne. Continuous-dosing birth control pills can reduce or eliminate menstrual periods.

- Antidepressants for PMDD and severe PMS. Fluoxetine (Sarafem, Prozac, generic), sertraline (Zoloft, generic), and paroxetine (Paxil, generic) are approved for treatment of PMDD.

- Anti-anxiety drugs for severe PMS-related anxiety.

Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy may be an appropriate alternative to antidepressants for some women.

Lifestyle Changes

A healthy lifestyle, including regular exercise and a healthy diet, is the first step towards managing PMS. For many women with mild symptoms, lifestyle approaches are sufficient to control symptoms.

Dietary Factors

Women should follow the general guidelines for a healthy diet. These guidelines include eating plenty of whole grains and fresh fruits and vegetables and avoiding saturated fats and commercial junk foods. Making dietary adjustments starting about 14 days before a period may help control premenstrual symptoms:

- Drink plenty of fluids (water is best) to help reduce bloating, fluid retention, and other symptoms. Avoid sugary drinks such as sodas and caffeinated drinks.

- Avoid or limit alcohol and caffeine.

- Eat frequent small meals, with no more than 3 hours between snacks, and avoid overeating. Overeating sugar-rich or salty foods may worsen some PMS symptoms, including water retention and negative mood. Be sure to limit your sodium (salt) intake.

- Choose high-fiber foods such as fruit, vegetables, and whole grains. Calcium-rich foods such as low-fat dairy products are also a good choice.

Vitamins and Minerals

Some evidence indicates that calcium, and other minerals and vitamins, may help with PMS symptoms.

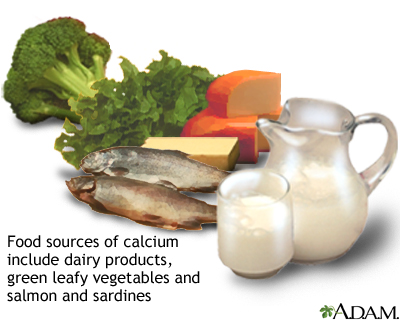

Calcium

Calcium has the most evidence as an effective dietary treatment for PMS. The recommended dietary intake for women is 1,000 mg/day ages 19 to 50 years and 1,200 mg/day after age 50. Calcium-rich foods include dairy products, dark green vegetables, nuts, grains, beans, and canned salmon and sardines. Food sources provide the most nutritional value, but supplements may be helpful for certain women.

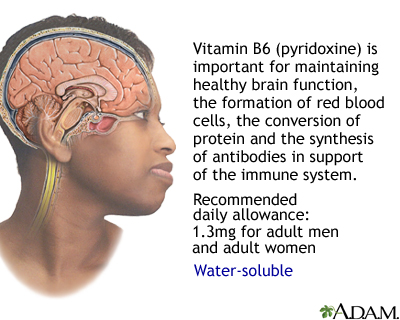

Vitamin B6

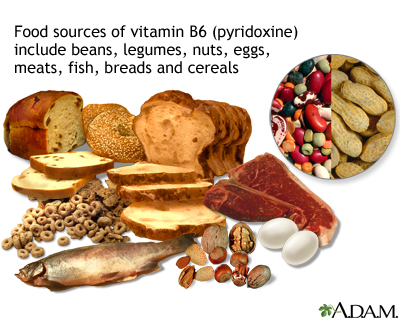

Limited clinical evidence suggests that vitamin B6 may help reduce PMS symptoms. The recommended daily intake for adult women before age 50 is 1.3 mg/day and after age 50 is 1.5 mg/day. Very high doses over long periods can cause nerve damage with symptoms of numbness in the feet and hands.

Food sources of B6 include meats, oily fish, poultry, whole grains, dried fortified cereals, soybeans, avocados, baked potatoes with skins, watermelon, plantains, bananas, peanuts, and brewer's yeast.

Other B Vitamins

Other B vitamins that may play a role in PMS include riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), and folate (folic acid). Food sources for these vitamins include:

- Riboflavin. Dairy products, leafy green vegetables, liver, tomatoes, mushrooms, almonds.

- Niacin. Dairy products, chicken, beef (especially liver), tuna, salmon, nuts, mushrooms, leafy vegetables, whole grain cereals, avocados, tomatoes, broccoli, asparagus.

- Folate. Leafy green vegetables, citrus fruits, dried beans, and folate-enriched cereals, breads, and pastas.

Magnesium

The effects of magnesium are not as well established as with calcium, but some evidence suggests that it may be helpful in reducing fluid retention in women with mild PMS. Causes of magnesium deficiencies include excessive alcohol, salt, soda, and coffee intake, as well as profuse sweating, intense stress, and heavy menstrual bleeding. Magnesium can be toxic in high amounts and can interact with certain drugs. Discuss with your doctor whether you should take a magnesium supplement.

Iron

Some research suggests that women who consume a diet high in plant-based (non-heme) iron have a lower risk for PMS symptoms. Dietary sources of plant-based iron include lentils, beans, spinach, and iron-fortified cereal. Plant-based iron is also available in supplement form, but it is important for women not to consume more than 45 mg/day. The recommended dietary allowance for iron in adult women is 18 mg/day under the age of 50 and 8 mg/day after that age.

Exercise and Stress Reduction

Exercise, especially aerobic exercise, increases natural opioids in the brain (endorphins) and improves mood. Exercise is also very important for maintaining good physical health. Even moderate exercise, such as taking a 30-minute walk every day, is beneficial. Although not an aerobic exercise, yoga releases muscle tension, regulates breathing, and reduces stress. Relaxation techniques, including meditation, can also help reduce stress.

Physical activity contributes to health by reducing the heart rate, decreasing the risk for cardiovascular disease, and reducing the amount of bone loss that is associated with age and osteoporosis. Physical activity also helps the body use calories more efficiently, thereby helping in weight loss and maintenance. It can also increase basal metabolic rate, reduce appetite, and help reduce body fat.

Improved Sleep

Many women with PMS suffer from sleep problems, either sleeping too much or too little. Achieving better sleep habits may help relieve symptoms.

Sleep problems

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of insomnia.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

A number of herbal remedies are used for PMS symptoms. Studies have not found any herbal or dietary supplement remedy to be any more effective than placebo for relieving PMS symptoms.

Chasteberry Extract

Chasteberry (Vitex agnus castus) is a traditional herbal remedy for many gynecological conditions. Some small studies have indicated it may be helpful for PMS symptoms, including breast discomfort. However, the evidence is not strong.

Evening Primrose Oil

Some women find that taking evening primrose oil helps improve PMS and symptoms such as breast tenderness. However, several rigorous studies have reported no benefit.

Ginger Tea

Ginger tea is safe and may help soothe mild nausea and other minor symptoms of PMS.

The following are special concerns for people taking natural remedies for PMS:

- St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum). Is an herbal remedy that may help some patients with mild-to-moderate depression. It can increase the risk for bleeding when used with blood-thinning drugs. It can also reduce the effectiveness of certain drugs, including cancer and HIV treatments. St. John's wort can increase sensitivity to sunlight.

- Dong quai is a Chinese herb used to treat menstrual symptoms. Dong quai can lengthen the time it takes for blood to clot. People with bleeding disorders should not use dong quai. Dong quai should not be taken with drugs that prevent blood clotting, such as warfarin or aspirin.

- L-tryptophan supplements have caused eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) in some people. EMS is a disorder that elevates levels of certain white blood cells and can be fatal.

Medications

Pain Relievers

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs block prostaglandins, substances that cause inflammation. NSAIDs are usually among the first drugs recommended for almost any kind of minor pain.

The most common NSAIDs used for menstrual cramps (or dysmenorrhea) are nonprescription ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, Midol, and generic) and naproxen (Aleve, generic) or prescription mefenamic acid (Postel, generic). NSAIDs are most helpful when started before menstruation and continued for 4 days into the cycle. Long-term daily use of any NSAID can increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) is a good alternative to NSAIDs, especially when stomach problems, ulcers, or allergic reactions prohibit their use. Products that combine acetaminophen with other drugs that reduce PMS symptoms may be helpful. Brands include Pamprin and Premsyn, which are also available as generic medication. Such drugs typically include a diuretic to reduce fluid retention and an antihistamine to relieve irritability.

Antidepressants

Selective Serotonin-Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs are the first line of treatment for PMDD and severe PMS mood symptoms.

In the United States, three SSRIs are approved by the FDA for the treatment of PMDD:

- Fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem, generic)

- Sertraline (Zoloft, generic)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, generic)

Other SSRIs sometimes prescribed for PMDD include citalopram (Celexa, generic) and escitalopram (Lexapro, generic). The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Effexor, generic) has also shown benefit in some studies.

SSRIs appear to work much faster for relieving PMS-related depression than when used to treat major depression. These drugs are typically prescribed with either continuous (daily) dosing throughout the month or an intermittent dosing regimen. With intermittent dosing, women take the antidepressant during the 14-day premenstrual period of their luteal phase.

Depression

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of depression.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

General side effects of SSRIs may include nausea, drowsiness, headache, weight gain and sexual dysfunction. Antidepressants may increase the risk for suicidal thinking and behavior in young adults ages 18 to 24. This risk for suicidality generally occurs during the first few months of treatment.

Anti-anxiety Drugs

Anti-anxiety drugs (called anxiolytics) may be helpful for women with severe premenstrual anxiety that is not relieved by SSRIs or other treatments.

Benzodiazepines

Alprazolam (Xanax) is a benzodiazepine anxiolytic often prescribed for PMS. However, benzodiazepines can have serious side effects. Dependence is a risk and can occur after as short a time as 3 months of use. Using alprazolam for only a few days per month when symptoms are most severe reduces this risk.

Common side effects include daytime drowsiness and a hung-over feeling. Respiratory problems may be worsened. Benzodiazepines also increase appetite, particularly for fatty foods. Overdose is very serious, although rarely fatal. Benzodiazepines are potentially dangerous when used in combination with alcohol.

Buspirone

Buspirone (BuSpar, generic) is a drug used to treat anxiety. It may help reduce premenstrual irritability. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone is not addictive. Buspirone also seems to have less pronounced side effects than benzodiazepines and no withdrawal effects, even when the drug is discontinued quickly. Common side effects include dizziness, drowsiness, and nausea.

Anxiety

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of anxiety.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Hormone Therapies

Hormone therapies are used to interrupt the hormonal cycle that triggers PMS symptoms. One method to accomplish this is through birth control pills.

Birth control

An in-depth report on the birth control options available to women.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Birth Control Pills

Oral contraceptives (OCs) contain combinations of an estrogen (usually estradiol) and a progestin (the synthetic form of progesterone).

The combination birth control pill Yaz is approved specifically for treatment of premenstrual dysmorphic disorder (PMDD). A related birth control pill, Beyaz, which is supplemented with the B vitamin folate, is also approved for treatment of PMDD. Both of these pills contain a newer type of progestin called drospirenone.

The FDA warns that birth control pills that contain drospirenone may increase the risk for blood clots much more than the progestin levonorgestrel contained in other types of birth control pills. Some studies have indicated that the risk for blood clots is 3 times higher with drospirenone.

Because of the high risk for blood clots, stroke, and heart attack, Yaz and Beyaz should not be used by women who are over age 35 or by those who smoke. In addition, Yaz and Beyaz should not be used by women with kidney, liver, or adrenal disease. Drospirenone is related to spironolactone, a diuretic, and can increase potassium levels.

Some women with PMS use extended-cycle (continuous-dosing) OCs to reduce or eliminate their monthly periods:

- Seasonique and Seasonale reduce periods to about 3 or 4 times a year

- Lybrel eliminates monthly periods in most women (some women continue to experience spotting)

Side effects of OCs include nausea, breakthrough bleeding, breast tenderness, headache (which may worsen in smokers or women with a history of migraine), and weight gain. Women who are over age 35 and smoke, or who are at risk for blood clots, heart attack, or stroke, should not take combination birth control pills. Some women may experience worsening of PMS symptoms with OCs.

GnRH Agonists

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (also called analogs) are powerful hormonal drugs that suppress ovulation and, thereby, the hormonal fluctuations that produce PMS. They are sometimes used for very severe PMS symptoms and to improve breast tenderness, fatigue, and irritability. GnRH analogs appear to have little effect on depression.

GnRH agonists include the implant goserelin (Zoladex), a monthly injection of leuprolide (Lupron Depot, generic), and the nasal spray nafarelin (Synarel).

Common side effects (which can be severe in some women) include menopausal-like symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweat, weight change, and depression. The side effects vary in intensity, depending on the particular GnRH agonist. The most important concern is possible osteoporosis from estrogen loss. Doctors recommend that women not take these drugs for more than 6 months.

Danazol

Danazol (Danocrine, generic) is a synthetic substance that resembles male hormones. It has very severe side effects and is used only if other therapies fail. It suppresses estrogen and menstruation and is used in low doses for severe PMS and premenstrual migraines. Side effects include masculinizing effects such as facial hair growth, deepening of the voice, and acne.

Diuretics for Fluid Retention

Diuretics are drugs that increase urination and help eliminate water and salt from the body. They reduce bloating and breast tenderness in women with PMS. Diuretics can have considerable side effects and should not be used for mild or moderate PMS symptoms. Spironolactone (Aldactone, generic) is the most commonly prescribed diuretic for PMS.

Spironolactone can increase potassium levels in the body. Women should be sure not to take additional potassium if they are taking spironolactone, and people with kidney disease should avoid this medication. Diuretics interact with a number of other drugs, including certain antidepressants. Women who are considering diuretics should let their doctors know of any other drugs or supplements that they are taking.

Acupuncture

A small amount of studies suggest a potential benefit of acupuncture but it has not been compared to other standard treatments for premenstrual syndrome. As a result, the role of acupuncture in treating this syndrome is unclear.

Resources

- National Women's Health Information Center -- www.womenshealth.gov

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

References

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 110: noncontraceptive uses of hormonal contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):206-218. PMID: 20027071 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20027071.

Appleton SM. Premenstrual Syndrome: Evidence-based Evaluation and Treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(1):52-61. PMID: 29298169 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29298169.

Armour M, Ee CC, Hao J, Wilson TM, Yao SS, Smith CA. Acupuncture and acupressure for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8(8):CD005290. PMID: 30105749 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30105749.

Fernández MDM, Saulyte J, Inskip HM, Takkouche B. Premenstrual syndrome and alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e019490. PMID: 29661913 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29661913.

Hofmeister S, Bodden S. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(3):236-240. PMID: 27479626 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27479626.

Lanza di Scalea T, Pearlstein T. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(2):201-216. PMID: 28477648 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28477648.

Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, Helmerhorst FM. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006586. PMID: 22336820 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22336820.

Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O'Brien PM, Wyatt K. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD001396. PMID: 23744611 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23744611.

Mendirata V, Lentz GM. Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Etiology, diagnosis, management. In: Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 37.

Reid RL, Soares CN. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Contemporary diagnosis and management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018; 40(2):215-223. PMID: 29132964 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29132964.

Sepede G, Sarchione F, Matarazzo I, Di Giannantonio M, Salerno RM. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder without comorbid psychiatric conditions: A systematic review of therapeutic options. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(5):241-261. PMID: 27454391 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27454391.

Yonkers KA, Simoni MK. Premenstrual disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):68-74. PMID: 28571724 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28571724.

Review Date: 3/23/2020

Reviewed By: John D. Jacobson, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda Center for Fertility, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.