Cervical cancer - InDepth

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cervical cancer.

Highlights

Cervical Cancer Screening

Cervical cancer is highly curable in its early stages. Regular screening can help detect this cancer at a precancerous phase. Cervical cancer screening uses two kinds of tests:

- The Pap test checks for abnormal changes in cervical cells that may indicate cancer or precancerous lesions. The Pap test is the main test used for cervical cancer screening.

- The HPV DNA test checks for the presence of high-risk strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) that cause cervical cancer. The HPV test may be used along with a Pap test or after a woman has had an abnormal Pap test result. In 2014, the FDA approved the HPV test as a single primary screening test, but its use this way is controversial.

Current cervical cancer screening guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend:

- Women ages 21 to 29 should be screened once every 3 years with a Pap test.

- Women ages 30 to 65 should be screened with either a Pap test every 3 years or a Pap test and HPV test every 5 years, assuming the HPV test is negative. Cancer experts are considering whether HPV testing guidelines should be changed.

- Women age 65 and older no longer need Pap tests as long as they have had consecutive screenings with normal results over the last 10 years. Women who have been diagnosed with pre-cancer and women with severe immunologic issues should continue to receive regular screenings.

HPV Vaccination

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted disease. High-risk strains (types) of HPV cause cervical cancer, as well as other types of cancer including vaginal, vulvar, anal, and head and neck cancers. Low-risk strains of HPV cause genital warts. Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV.

A vaccine (Gardasil 9) is available to prevent (not treat) cervical cancer in girls and young women. This vaccine protects against 9 types of HPV that cause cervical, vaginal, vulvar, and anal cancers. It also protects boys and young men against genital warts.

Drug Approval

In recent years, the FDA approved the biologic drugs bevacizumab (Avastin) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for treatment of persistent, recurrent, or advanced cervical cancer.

Introduction

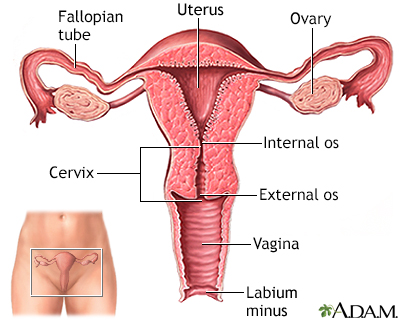

The cervix is the lower part of the uterus (womb). It connects the uterus to the vagina. The opening of the cervix, called the os, is at the top of the vagina. It remains small and narrow, except during childbirth when it widens to allow a baby to pass from the uterus into the vagina.

Uterus

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ located in the female pelvis between the bladder and rectum. The ovaries produce the eggs that travel through the fallopian tubes. Once the egg has left the ovary it can be fertilized and implant itself in the lining of the uterus. The main function of the uterus is to nourish the developing fetus prior to birth.

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ located in the female pelvis between the bladder and rectum. The main function of the uterus is to nourish the developing fetus prior to birth. During childbirth, the cervix expands to allow the baby to pass through the birth canal (vagina).

Cervical cancer develops in the thin layer of cells called the epithelium, which cover the cervix. Cells found in this tissue have different shapes and give rise to different cancers:

- Squamous cells (flat and scaly) are the same type of cells that make up the skin. Most cervical cancers arise from changes in the squamous cells of the epithelium and are termed squamous cell carcinomas.

- Glandular cells (column-like) line the cervical glands. Cancers arising from these cells are known as adenocarcinomas.

- Adenosquamous carcinomas contain both types of cells and combine features of both squamous cells carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

Cervical cancer usually begins slowly with precancerous abnormalities. If cancer develops, it generally progresses very gradually. Cervical cancer usually takes about 10 to 20 years to develop.

Cervical cancer is an often preventable type of cancer and is very treatable in its early stages. Regular Pap test and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening can help detect this disease in its early pre-invasive states before it develops into true cancer.

Pre-Cancerous Changes in the Cervix

Dysplasia means abnormal growth and refers to a pre-cancerous condition. In the case of the cervix, dysplasia indicates that some cells on the outside of the cervix (squamous epithelial cells) are abnormal in size and shape and are beginning to grow in an abnormal fashion. However, the abnormal cells are still confined to the surface (epithelial layer). These abnormal cells may eventually become cancerous, but this does not always happen.

Pap test screening can help identify abnormal cells that may be pre-cancerous, but a biopsy is necessary for confirmation. In a biopsy test result, pre-cancerous cells are classified as cervical dysplasia, now called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

(For more information on pre-cancer, see the Diagnosis and Screening section of this report.)

Cervical neoplasia

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is the presence of abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix. A Pap smear and colposcopy are two of the procedures performed to monitor the cells and appearance of the cervix.

Invasive Cervical Cancer

The cells of the epithelium rest on a very thin layer called the basement membrane. Invasive cervical cancer occurs when abnormal cells, (cancer cells) in the epithelium cross this membrane and invade the stroma, the underlying supportive tissue of the cervix. The cancer may then move into adjacent tissues or penetrate into blood or lymphatic vessels.

In early stages, the cancer is confined to the cervix. In later stages, the original cancer may spread to areas surrounding the uterus and cervix or into nearby organs such as the bladder or rectum. As cancer advances, it may spread further (metastasize) to distant sites in the body through the bloodstream or the lymph nodes.

Causes

Human Papillomavirus

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main cause and risk factor of cervical cancer. Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV. In general, doctors assume that a woman with cervical cancer has been infected with HPV.

HPV is a very common sexually transmitted virus. There are many different types of HPV:

- Low-risk HPV types, such as HPV 6 and HPV 11, cause genital warts and are rarely associated with cancer, but can be associated with mild dysplasias of the cervix.

- High-risk HPV types cause cervical cancer, as well as cancers of the vagina, vulva, anus, penis, oropharynx (throat, tongue, soft palate), and possibly lung.

- HPV 16 and HPV 18 are the causes of most cases of cervical cancer.

Nearly all people are infected with HPV at some point in their lives. HPV usually goes away as a result of the body's immune system fighting off infection. Only 10% of women remain infected for more than 5 years, and sometimes HPV does not go away. A chronic, long-term infection with a high-risk type of HPV can cause changes in cervical cells that eventually lead to cancer.

HPV infection is spread primarily by having sex with a partner infected with HPV. It is transmitted through skin-to-skin contact with infected areas of the genitals, anus, or mouth. Using condoms and limiting the number of sexual partners can help reduce the risk of contracting HPV.

Risk Factors

Age

Cervical cancer is extremely rare in women younger than age 20. The median age of diagnosis is 49 years. Nearly half of all cervical cancer diagnoses occur in women ages 35 to 54 years. About 20% of cervical cancer diagnoses occur in women over 65 years of age, mostly in women who did not receive regular cancer screening during their younger years.

Race and Poverty

In the United States, Hispanic women are most likely to develop cervical cancer, followed by African American women. African American women have the highest death rate from cervical cancer. White and Asian women have a lower risk for being diagnosed with and dying from cervical cancer.

Some of these differences are probably related to socioeconomic factors. Many studies report that high poverty levels are linked with low screening rates. In addition, lack of health insurance, limited transportation, and language difficulties often hinder a poor woman's access to screening services. It is estimated that half of all women with cervical cancer in the United States have never had a Pap test.

Sexual History

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main risk factor for cervical cancer. The most important risk factor for HPV infection is sexual activity with an infected person. Women most at risk for cervical cancer are those with a history of multiple sexual partners, sexual intercourse at age 17 years or younger, or both. A woman who has never been sexually active has a very low risk for developing cervical cancer.

Sexual activity with multiple partners increases the likelihood of many other sexually transmitted infections (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis). Studies have found an association between chlamydia and cervical cancer risk, including the possibility that chlamydia may prolong HPV infection.

Family History

Women have a higher risk of cervical cancer if they have a first-degree relative (mother, sister) who has had cervical cancer. This is probably because of similar socio-economic factors as opposed to a hereditary association.

Use of Oral Contraceptives

Long-term use of birth control pills, or oral contraceptives (OCs), may increase the risk for cervical cancer. Women who take OCs for more than 5 to 10 years appear to have a higher risk for HPV infection than those who do not use OCs. Women taking OCs for fewer than 5 years do not have a significantly higher risk.

The reasons for this risk from OC use are not entirely clear. Some research suggests that the hormones in OCs might help the virus enter the genetic material of cervical cells. Another possible reason is that women who use OCs may be less likely to use barrier methods, such as condoms. Latex condoms can help reduce, although not eliminate, the risk of HPV transmission and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Having Many Children

Having given birth to three or more children may increase the risk for cervical cancer.

Smoking

Smoking is associated with a higher risk for pre-cancerous changes (dysplasia) in the cervix and for progression to invasive cervical cancer.

Immunosuppression

Women with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, or on immunosuppressing drugs, such as prednisone, or transplant anti-rejection drugs are more susceptible to acquiring HPV. Immunocompromised people are also at higher risk for having cervical pre-cancer develop rapidly into invasive cancer.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES)

From 1938 to 1971, diethylstilbestrol (DES), an estrogen-related drug, was widely prescribed to pregnant women to help prevent miscarriages. The daughters of these women face a higher risk of an unusual type of cervical and vaginal cancer called clear cell carcinoma, as well as other gynecological problems. DES is no longer prescribed. Virtually all the women at risk for this problem have grown out of the age group at which these diseases were seen.

Prevention

The best ways to prevent cervical cancer are:

- Avoid getting infected with human papillomavirus (HPV). Because HPV is sexually transmitted, practicing safer sex and limiting the number of sexual partners can help reduce risk.

- Get vaccinated before becoming sexually active. A vaccine can protect against the major cancer-causing HPV strains in girls and young women who have not yet been exposed to the virus.

- Have regular screenings. Pap tests are the most effective way of detecting cervical cancer while it is in its earliest pre-cancerous stages and preventing the development of invasive cervical cancer.

HPV Vaccine

Gardasil 9 is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prevent either HPV or cervical cancer. It protects against 9 HPV types, including types 16 and 18, the HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer and other lower genital tract cancers. It also protects against HPV types 6 and 11, which cause genital warts, and against 5 additional HPV strains.

Gardasil 9 is approved for:

- Girls and women ages 9 to 45 to prevent cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer caused by the HPV virus and to prevent genital warts.

- Boys and men ages 9 to 45 years to prevent genital warts and anal cancer.

Current immunization guidelines for females recommend:

- Routine vaccination between ages 11 to 12 years. Girls as young as age 9 can receive the vaccine.

- Between ages 9 through 14, the vaccine should be given in 2 doses, with the second dose given after 6 to 12 months of first dose.

- If the vaccine is given at age 15 or older, it should be administered in 3 doses, with the second and third doses given 2 and 6 months after the first dose. The HPV vaccine can be given at the same time as other vaccines.

- Girls and women ages 13 to 45 who have not been previously immunized or who have not completed the full vaccine series should discuss with their health care provider about catching up on missed doses.

- Women should not get the vaccine during pregnancy.

Current immunization guidelines for males recommend:

- A routine 2-dose vaccination with Gardasil 9 is recommended for all boys ages 11 to 12.

- The vaccine is recommended for all men through age 45, but is most effective when given at a younger age.

- If the vaccine is given at age 15 or older, it should be administered in 3 doses, with the second and third doses given 2 and 6 months after the first dose.

The HPV vaccine can only prevent, not treat:

- HPV infection

- Genital warts

- Cervical cancer

Because the vaccine cannot protect against HPV types with which people are already infected, doctors recommend that girls and boys get vaccinated before they become sexually active.

Studies indicate that the vaccine is nearly 100% effective in preventing cervical cancer and genital warts caused by the HPV types covered in the vaccine when given prior to HPV exposure. However, young women who are sexually active may still derive some benefit from the vaccine, at least for protection against any of the four HPV strains that they have not yet acquired.

The most common side effects of the vaccine include:

- Discomfort or pain at the injection site

- Headache

- Mild fever

These vaccines do not protect against all types of cancer-causing HPV. Women should still receive regular screening to detect any early signs of cervical cancer. For girls and women who have been sexually active before they receive the vaccine, screening still provides the best protection against cervical cancer.

Condoms

Condoms provide some protection against HPV as well as other sexually transmitted infections.

Male circumcision may possibly reduce the risk of HPV, but it does not completely prevent it. Men who are circumcised should still use condoms.

Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)

Some evidence suggests that the intrauterine device (IUD) may help protect against cervical cancer. The IUD is a type of birth control that is inserted into the uterus by a health professional. It is a small plastic T-shaped device that contains either the hormone progesterone or copper.

Researchers are not certain exactly how the IUD reduces cervical cancer risk, but some think that the process of inserting or removing the device may destroy pre-cancerous lesions. Another possible explanation is that the IUD causes a low-grade infection in the cervix, which interferes with HPV establishing itself in the cervix.

Pap Tests

Regular Pap tests are the most effective way to diagnose cervical cancer when it is still in its earliest, most curable stages. In some cases, a HPV test may be used either along with the Pap test or in place of it. [For more information, see Diagnosis and Screening section of this report.]

Prognosis

Prognosis for cervical cancer depends on the:

- Stage of the cancer

- Type of cervical cancer

- Size of the tumor

The earlier that cervical cancer is detected, the better the odds for survival.

Symptoms

Most women with dysplasia (pre-cancer) or pre-invasive cancer have no symptoms. This is why screening tests are so important.

Symptoms of invasive cancer may include:

- Unusual vaginal bleeding. Bleeding may stop and start again between regular periods, or there may be bleeding after menopause. Unexpected bleeding can also occur after intercourse or a pelvic exam. Menstrual periods sometimes last longer or are heavier than usual.

- Increased vaginal discharge, which may contain blood. The discharge may occur between periods or after menopause.

- Pelvic pain or pain during sexual intercourse.

- Swelling in the legs or enlarged lymph nodes in the groin or neck may be associated with the advanced stage of the disease.

These symptoms are not exclusive to cervical cancer. Sexually transmitted diseases, for instance, can cause similar symptoms.

Diagnosis and Screening

The changes that lead to cervical cancer develop slowly. Screening tests performed during regular gynecologic examinations can detect early changes. The two tests used for cervical cancer screening are:

- The Pap test, which can detect pre-cancerous cell changes and cervical cancer. This test is used for all women ages 21 to 65.

- The HPV (human papillomavirus) test, which may be used along with a Pap test or after a woman has an abnormal Pap test result. It may also be used as a primary test. The HPV test can identify the high-risk types of HPV that are known to cause cervical cancer. This test is generally not used for women younger than age 30 because HPV is very common in this age group. In younger women, the virus usually goes away within 2 years as a result of the body successfully fighting it off.

Pap Test

The Papanicolaou test, better known as the Pap test or Pap smear, can help detect cervical cancer when it is in its earliest stages. It can also detect pre-cancerous changes in cells.

Use of the Pap test has significantly reduced the death rate from cervical cancer. Most cases of cervical cancer occur in women who have not had regular Pap tests.

Preparing for a Pap Test

Doctors recommend scheduling a Pap test 10 to 20 days after menstruation begins to get the most accurate results. The Pap test should not be performed during menstruation.

In the 24 to 48 hours before the test, DO NOT:

- Have sexual intercourse

- Use vaginal spermicides, lubricants, or tampons

- Douche

Pap Test Procedure

A Pap test is usually painless, although some women may have mild discomfort:

- The test is done in a medical office. The woman removes her clothes from the waist down and puts on a medical gown. She lies on her back on the examination table, bends her knees, and puts her feet in supports (called stirrups) at the end of the table.

- The health care provider inserts a plastic or metal device (called a speculum) into her vagina to widen it.

- Using a spatula, brush, or both, the provider gently scrapes the surface of the cervix, and sometimes the upper vagina, to gather living cells. The provider will also obtain cells from inside the cervical canal. The scraping is completely painless.

- The cells are preserved either on a glass slide or, now more commonly, in liquid. They are processed at the lab and stained for microscopic viewing, and then analyzed under a microscope by a specialist known as a cytopathologist. One of the advantages of the liquid-based test is that the same specimen can be used for additional tests (HPV, other STIs, and vaginal infections).

Pap smear

A Pap test is a simple, relatively inexpensive procedure that can easily detect cancerous or precancerous conditions.

A Pap test is a simple, relatively inexpensive procedure that can easily detect cancerous or pre-cancerous conditions.

Reliability and Accuracy

The Pap test is not a perfectly reliable measure of a woman's risk for cervical cancer. Sometimes it misses the presence of cancer or pre-cancer cells, which is called a false-negative result. However, if abnormal cells are missed on one test, they are likely to be spotted during the next one, hopefully while they are still in the pre-cancerous state, which makes treatment significantly easier and safer.

It is also possible for a test to indicate abnormal cells when the cells are really normal, a so-called false positive result. If a test indicates possible abnormal cells, your provider will order another Pap test or other tests to confirm the results.

HPV DNA Test

For an HPV DNA test, the provider collects a sample of the cervical cells the same way (and usually at the same time) as the Pap test. This test looks for the types of human papillomavirus (particularly HPV 16 and HPV 18) that cause cervical cancer by analyzing the DNA of the cervical cells.

The HPV test can be used along with the Pap test to screen for cervical cancer in women ages 30 years and older. It is also approved as a single test for women ages 25 and older to see if they need further diagnostic testing with a Pap test or colposcopy. The test can provide information on a women's risk of developing cervical cancer in the future.

Current Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations

General guidelines for cervical cancer screening recommend:

- Initial Screening. Women should begin to have Pap tests at age 21 regardless of whether or not they have been sexually active. Women under age 21 should not be screened.

- Women Ages 21 to 29. Women ages 21 to 29 who are at average risk for cervical cancer should be screened once every 3 years with a Pap test. They do not need an HPV DNA test unless they have had an abnormal Pap test result. In 2014, the FDA approved an HPV test as primary screening for women ages 25 and older. Cancer experts are currently reviewing guidelines on how the HPV test should be used.

- Women Ages 30 to 65. Women in this age bracket can have either a Pap test every 3 years or a Pap test and HPV test every 5 years.

- Women Ages 65 and Older. Women age 65 and older no longer need Pap tests as long as they have had regular Pap tests with normal results. Women who have been diagnosed with pre-cancer should continue to receive regular screenings.

- After a Hysterectomy. Women who have had a hysterectomy that preserves the cervix (called a supracervical hysterectomy) should continue to have Pap screening according to the guidelines listed above. Women who have had their cervix removed at the time of hysterectomy no longer need Pap tests, unless the hysterectomy was done for cervical cancer or pre-cancer in which cases screening should be continued.

Pap Test Results

The cells viewed in a cervical smear sample are classified on a scale representing the spectrum of cell changes from normal to cancerous. The Pap test is first characterized as either normal or abnormal.

The Bethesda System (TBS) is used to report Pap test results. It classifies abnormal results as:

- Atypical squamous cells (ASC with subtypes of ASC-US and ASC-H)

- Squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs)

- Atypical glandular cells

Atypical Squamous Cells (ASC)

ASCs are mildly abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix. It is difficult to know if they are pre-cancerous. They may be normal cells with changes simply caused by inflammation. ASCs are further categorized as ASC-US or ASC-H:

- ASC-US. Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) are the lowest risk abnormal cells and are most often not pre-cancerous. Women with ASC-US need to have a repeat Pap test in 6 to 12 months and the doctor may also recommend an HPV test and possibly colposcopy.

- ASC-H. This category refers to ASC that may indicate high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL). Such women have a higher risk of having CIN II and III (moderate or severe dysplasia) and hence are at risk for development of cervical cancer. They are referred for colposcopy.

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (SILs)

SILs are classified as either low-grade (LGSIL) or high-grade (HGSIL). High-grade SILs are more serious than low-grade SILs, and need to be treated because they can develop into invasive cancer. Pap tests can suggest the presence of SILs but not their grade. Women with SILs discovered through a Pap test should undergo colposcopy. A colposcopy can determine whether SILs are high-grade or low-grade and whether treatment is required.

Atypical Glandular Cells and Adenocarcinoma

Atypical glandular cells pose a higher risk for the presence of cancerous changes than atypical squamous cells. Women with atypical glandular cells need a pelvic ultrasound, colposcopy, and endocervical and endometrial testing, to rule out the presence of cancer. Adenocarcinoma refers to glandular cells that are cancerous.

Colposcopy and Biopsy

The Pap test shows only the presence of abnormal cells. It is useful simply as a screening test that identifies women who may have pre-invasive or early cancerous changes. For a diagnosis, the next step is usually colposcopy, during which the cervix is visualized under low power magnification. The doctor takes small samples of the cervix for biopsies. A biopsy will determine the grade of the pre-cancerous growth or whether invasive cancer is present.

Colposcopy Procedure

Colposcopy can be performed in a medical office without anesthesia in 10 to 15 minutes. It causes about as much discomfort as mild menstrual cramps:

- First, using a speculum to keep the vagina open, the doctor aims a light at the cervix.

- The doctor then looks through the eyepiece of a special microscope, known as a colposcope, to view the cervix. Application of dilute acetic acid (vinegar) helps bring out the changes caused by SILs.

- A small sample (biopsy) of the cervical tissue is pinched off using forceps.

- After the biopsy, an endocervical scraping (curettage) may be performed to test the tissues of the cervix above the area that can be seen. The doctor uses a spoon-shaped instrument called a curette to scrape tissue from the lining of the endocervical canal, which runs between the cervix and the uterus.

Colposcopy-directed biopsy

A colposcopy-directed biopsy is a procedure in which the cervix is examined with a colposcope for abnormalities and a tissue sample is taken.

Conization, or cone biopsy, is a more invasive way of doing a biopsy. It is a surgical procedure that uses a scalpel (cold knife biopsy), laser beam, or a wire loop heated by electrical current (LEEP procedure) to remove a larger piece of the cervix. Conization may be performed as a diagnostic procedure, or as a treatment for pre-cancers or early-stage cancers.

Biopsy Results

The pre-cancerous changes from biopsy results of colposcopy are called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. They are graded according to severity as CIN I, CIN II, and CIN III:

- CIN I is classified as mild dysplasia. It is equivalent to a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL) identified by a Pap test. CIN I may progress if untreated but often goes away without treatment.

- CIN II is classified as moderate dysplasia. It is equivalent to a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) found in a Pap test.

- CIN III is classified as severe dysplasia. It is the most aggressive form of dysplasia. It is also equivalent to a HGSIL.

CIN III is considered the same as carcinoma in situ (CIS) or Stage 0 cervical cancer. In both CIN III and CIS the pre-cancerous cells still rest on the surface of the cervix and have not yet invaded through the basement membrane into the deeper tissues. However, if not surgically removed, there is a high chance that CIN III or CIS can progress to invasive cancer.

Follow-Up Procedures

Women with evidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) II and III or cervical cancer need treatment. Women with biopsies that show low-grade abnormal cells or CIN I, but whose cervix is otherwise normal, are generally given follow-up Pap tests or colposcopies.

If a biopsy detects invasive cancer, the woman will need additional tests to find out how far the cancer has spread. Tests to stage cancer may include imaging tests such as:

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Chest x-ray

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

Other special pelvic exam procedures may also be recommended.

Cervical Cancer Staging

After making a diagnosis, a doctor will classify the stage of the cancer according to the size of the primary tumor, and how far cancer has spread into the lining of the cervix, throughout the cervix, or beyond. Doctors use staging to determine treatment and prognosis.

The basic cervical cancer stages are:

- Stage 0. Cancer is confined only to cells on the lining (epithelium) of the cervix. It is also called carcinoma in situ and is equivalent to CIN III pre-invasive cancer.

- Stage I. Is invasive cancer, but the tumor is confined to the cervix.

- Stage II. Cancer has spread beyond the cervix and uterus, but it has not spread to the pelvic side wall or lower part of the vagina.

- Stage III. Cancer has spread to the lower part of the vagina or sides of the pelvis. It may become large enough to block the ureters of the kidney, which can cause the kidney to stop functioning.

- Stage IV. Is advanced (metastasized) cancer. The cancer has spread to other organs or parts of the body located near the cervix (bladder, rectum) or farther away (liver, lungs).

- Stages I to IV are further subdivided into A and B stages.

Treatment

Treatment of cervical cancer depends on:

- The stage of the cancer

- The size and shape of the tumor

- The woman's age and general health

- Her desire to have children in the future

Your cancer care team may include a gynecologist (doctor who specializes in the female reproductive system), gynecological oncologist (a gynecologist who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive organs), a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and other health care providers.

A cancer support group can help ease the stress of illness. Sharing with others who have common experiences and problems can help you not feel alone.

Treatment of Pre-Invasive Cancer

Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), including pre-invasive cancer, depends on the type and extent of abnormal changes. Very early pre-cancer (CIN I) often goes away on its own but needs follow-up Pap tests and colonoscopy to monitor the condition.

CIN II or CIN III may turn into invasive cancer if the affected area is not removed or destroyed. This is done using cryocauterization (freezing the cervix), conization with cold knife biopsy, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), or laser surgery.

Although not common for pre-invasive cancer, hysterectomy or less commonly, internal radiation therapy, may be recommended for some women.

Treatment of Invasive Cervical Cancer

Treatment for invasive cervical cancer depends on the stage of the cancer. Clinical trials investigating new treatment approaches are available for all stages of cervical cancer. Treatment approaches include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Surgery for cervical cancer includes:

- Conization.

- Total hysterectomy (removal of cervix and uterus), sometimes with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of both fallopian tubes and ovaries).

- Radical hysterectomy (removal of uterus, cervix, part of vagina, ligaments that support the uterus and cervix, and pelvic lymph nodes).

- Radical trachelectomy (removal of the cervix part of the vagina, the ligaments that support the uterus and cervix, and the pelvic lymph nodes, but not removing the uterus).

- Pelvic exenteration (radical hysterectomy, if the uterus is still present, along with removal of the bladder, vagina, rectum, or lower colon) for recurrent cancer (cancer that has come back after treatment).

Radiation treatments include:

- External beam radiation using radiation delivered by a machine outside the body.

- Internal radiation (brachytherapy) using radioactive implants placed inside the vagina.

- Radiation may be used as palliative therapy to ease symptoms in advanced (metastatic) cancer.

Chemotherapy uses cancer-killing drugs that are injected into a vein or taken by mouth. Chemotherapy may be used:

- Along with radiation (chemoradiation) to help the radiation kill the cancer cells.

- Along with targeted therapy (biologic drug) to treat persistent, recurrent, or late-stage cancer.

- As palliative therapy for advanced (metastatic) cancer.

Fertility Preservation

Some of the treatments used for cervical cancer can make a woman infertile. Women of child-bearing age should discuss with their cancer care team any concerns and questions they may have about how various cancer treatments could affect their fertility. They may also wish to have a consultation with a fertility specialist.

Some women with cervical cancer may be candidates for surgical procedures, such as ovarian transposition that preserves ovarian function or radical trachelectomy that preserves the uterus. Other women may want to consider assisted reproductive technology, such as embryo or oocyte (egg) cryopreservation ("freezing"). It is very important that you have these discussions with your health care team before you begin cancer treatment.

Surgery

Surgery is the primary treatment for most cases of early-stage cervical cancer.

Conization

Conization is a surgical procedure that removes a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. Conization may be performed using:

- Cold knife conization with a scalpel to cut out the tissue.

- Laser surgery, using a laser beam directed through the vagina to burn through the tissue. The laser beam acts like a knife to remove the tissue.

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) with a wire loop heated by an electrical current to slice through and remove the tissue.

LEEP and laser surgery can be performed in a medical office using local anesthesia. Cold knife conization is performed under general anesthesia in an operating room.

Conization does not usually affect a woman's fertility, although in a small percentage of cases it may result in cervical incompetence (inability for the cervix to hold a pregnancy). However, if conization is performed on a woman who is pregnant, it may cause miscarriage or severe bleeding.

Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy aims to eliminate the cancerous tissue by removing the uterus and cervix.

Hysterectomy

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of uterine fibroids.

Depending on the stage of the cervical cancer and how far it has spread, the woman may have either a total (simple) hysterectomy or a radical hysterectomy. In some cases, both fallopian tubes and ovaries may be removed (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy).

Total Hysterectomy

A total (also called simple) hysterectomy involves the removal of the uterus and the cervix, but leaves the parametria (ligaments and tissue that surround the uterus) and vagina intact. The uterus may be removed through an open abdominal incision or vaginally.

There are various ways to perform a hysterectomy, including vaginally or laparoscopically. Robotic-assisted hysterectomy is a type of laparoscopic hysterectomy, but the surgical instruments are attached to a robot. Robotic or laparoscopic procedures for cervical cancer may result in a worsened outcome compared to the open approach.

Radical Hysterectomy

A radical hysterectomy removes not only the uterus and the cervix but also the parametria, the supporting ligaments, and the upper vagina. Pelvic lymph nodes are usually removed at the same time in a procedure called lymphadenectomy. Radical hysterectomy may be performed through open abdominal surgery, or through vaginal, laparoscopic or robotic-assisted laparoscopic, methods.

Total recovery time is generally 2 to 3 weeks for vaginal hysterectomy and 4 to 6 weeks for abdominal hysterectomy. Radical hysterectomy may take several months for full recovery.

Hysterectomy causes infertility. After a hysterectomy, a woman no longer has menstrual periods and she can no longer become pregnant. Women retain their clitoris and vagina and can still experience sexual arousal and climax.

Menopause may begin a few years earlier than it naturally would. (Removal of the ovaries causes immediate menopause.) Women who have had a hysterectomy no longer need to have Pap tests because they have had their cervix removed, unless the hysterectomy was done as a treatment for cervical precancer or some other type of cancer, in which case screening needs to be continued.

Radical Trachelectomy

For some women, radical trachelectomy may be a fertility-sparing alternative to a hysterectomy. Radical trachelectomy involves removing the cervix, surrounding ligaments and tissue, and upper part of the vagina. The uterus is then reattached to the remaining vagina. The lymph nodes are usually removed as a separate laparoscopic procedure if the procedure is done vaginally, or as part of the procedure if an abdominal approach is used.

Women can usually resume normal activities in about 6 weeks. Radical trachelectomy poses a high risk for miscarriage during future pregnancy, but some women who have this procedure are able to carry a baby to term. The baby is delivered by cesarean section (C-section).

Pelvic Exenteration

If the tumor recurs or persists within the pelvis after treatment, a more extreme procedure called a pelvic exenteration may be recommended. Pelvic exenteration combines radical hysterectomy (if the uterus is still present) with the removal of the vagina, bladder, rectum, and part of the colon. The extensiveness of the surgery depends on where the cancer has spread and which of these organs needs to be removed.

The surgeon may perform a colostomy to create a new passage for the stool to leave the body, although occasionally the colon can be put back together, and will similarly construct a new urinary drainage system. If the vagina is removed, a plastic surgeon may be able to reconstruct a new one. Full recovery from pelvic exenteration can take 6 months or longer.

Radiation

Radiation therapy for cervical cancer is usually given along with chemotherapy. The combination treatment is called chemoradiation. Chemoradiation is used as a primary treatment for many stages of cervical cancer. Radiation may also be used as palliative therapy to ease symptoms and improve quality of life in late-stage cancer, and to treat recurrent cancer.

There are two types of radiation therapy:

- External beam radiation uses high-energy x-rays aimed at the pelvic area from an outside machine. It usually involves a short period of direct-radiation 5 days a week for about 4 to 6 weeks in an outpatient setting.

- Internal radiation (brachytherapy) involves placing radioactive capsules into the vagina and cervix. Low-dose brachytherapy is rarely used nowadays. It requires a hospital stay as the radioactive material is surgically implanted and left in place for several days. High-dose brachytherapy, the more common method, is given on an outpatient basis during several short treatments using a device that is inserted and removed at each session.

- Both internal and external types of radiation therapy may be used together to give the best results.

In order to be effective, radiation therapy must be powerful enough to destroy the cancer cells' ability to grow and divide. This means that normal cells are also affected, which can cause significant side effects. Fortunately, healthy cells usually recover quickly from the damage, whereas abnormal cells do not.

Side Effects

Side effects of radiation therapy may include fatigue, redness or dryness in the treated area, diarrhea, nausea, frequent or uncomfortable urination, and vaginal dryness, itching, or burning. After treatment, many side effects usually disappear.

Long-term side effects may include vaginal scarring (stenosis) and dryness, which can cause painful intercourse. Long-term effects on the bladder or intestines include:

- Chronic cystitis

- Colitis

- Blockages

- Fistula formation (abnormal connection between adjacent organs)

Discuss with your health care provider treatment options for this problem. Radiation doctors often prescribe dilators to help stretch the vaginal walls after treatment, which can help minimize some of these issues.

Radiation to the pelvic area may affect the ovaries and result in premature menopause. Ovarian transposition, which involves surgically moving one or both ovaries outside of the treatment field, may be a fertility-sparing option for some women who are undergoing pelvic radiation. This option may permit egg harvest after treatment, with the fetus carried by a surrogate. This option should be discussed with your cancer care team in advance of radiation therapy.

Female reproductive anatomy

Internal structures of the female reproductive anatomy include the uterus, ovaries, and cervix. External structures include the labium minora and majora, the vagina and the clitoris.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses cell-killing drugs to destroy cancer cells. Chemotherapy is usually used along with radiation (a combination called "chemoradiation") to help increase the effectiveness of radiation therapy. Chemoradiation is a primary treatment for many stages of cervical cancer.

In the most advanced cancer stage in which curative radiation therapy is not feasible, chemotherapy is used palliatively to help relieve symptoms associated with metastatic cancer.

Platinum-Based Drugs

Platinum-based drugs are the main chemotherapy treatment for cervical cancer. Cisplatin is the primary drug used. Carboplatin is an alternative platinum drug for women who cannot tolerate cisplatin. These drugs may be used alone or in combination with paclitaxel.

Other drugs

Other drugs that may be used alone or in combination include paclitaxel, topotecan, gemcitabine, 5-FU, and others.

Bevacizumab (Avastin) and Pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

Bevacizumab and pembrolizumab are biologic drugs approved to treat persistent, recurrent, or advanced (metastatic) cervical cancer. They are both monoclonal antibodies that target proteins with roles in cancer growth.

Bevacizumab blocks a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) that helps new blood vessels form. By blocking VEGF-A, bevacizumab slows the growth of the tumor.

Pembrolizumab blocks the lymphocyte receptor for a protein called programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1). Cancer cells that have PD-L1 are protected from being attacked by the body's immune system. Pembrolizumab blocks this process and allows lymphocytes to attack the cancer cells. It is given to patients who test positive for PD-L1.

Bevacizumab may be given in combination with paclitaxel and cisplatin, or paclitaxel and topotecan.

Administration

Chemotherapy is usually given intravenously at a medical center or office. The drugs are given in cycles with a period of rest following a period of treatment, to allow recovery from the side effects.

Side Effects

Side effects are common with chemotherapy. They vary depending on the drug, or combinations of drugs, used.

Common side effects may include:

- Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- Temporary hair loss

- Loss of appetite and weight

- Fatigue

More serious side effects can include:

- Severe drop in white blood cell count (neutropenia), which can increase the risk for infections.

- Reduction of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia), which can lead to bruising.

- Reduction in red blood cell count (anemia), which can cause fatigue and shortness of breath.

- Nerve damage (neuropathy), which can give sensations of numbness or tingling in the hands and feet or result in hearing loss.

- Menstrual changes or premature menopause.

- Kidney damage, which can be severe and in rare cases permanent.

Many side effects are temporary and go away once treatment is completed. Other side effects may take longer to stop or may be permanent. Discuss with your cancer care team any side effects you might experience. Some side effects can be treated or prevented with drugs or other therapies.

Resources

- National Cancer Institute -- www.cancer.gov

- American Cancer Society -- www.cancer.org

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

- American Sexual Health Association -- www.ashasexualhealth.org

- National Cervical Cancer Coalition -- www.nccc-online.org

- Foundation for Women's Cancer -- www.foundationforwomenscancer.org

- Cancer.Net -- www.cancer.net

Reviewed By

Howard Goodman, MD, Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, West Palm Beach, FL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion No. 641: human papillomavirus vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):e38-e43. PMID: 26287792 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26287792.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 140: management of abnormal cervical cancer screening test results and cervical cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1338-1367. PMID: 24264713 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24264713.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Practice bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e111-e130. PMID: 27661651 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27661651.

Borcoman E, Le Tourneau C. Pembrolizumab in cervical cancer: latest evidence and clinical usefulness. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9(6):431-439. PMID: 28607581 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28607581.

Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):169-182. PMID: 30638582 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30638582.

Goodman A. HPV testing as a screen for cervical cancer. BMJ. 2015;350:h2372. PMID: 26126623 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26126623.

Jhingran A, Russell AH, Seiden MV, et al. Cancers of the cervix, vulva, and vagina. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 84.

Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, et al.; Broad Spectrum HPV Vaccine Study. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711-723. PMID: 25693011 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25693011.

Kim DK, Hunter P. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(5):115-118. PMID: 30730868 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30730868.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cervical Cancer. Version 5.2019. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf. Updated September 16, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2019.

Salcedo MP, Baker ES, Schmeler KM. Intraepithelial neoplasia of the lower genital tract (cervix, vagina, vulva): etiology, screening, diagnostic techniques, management. In: Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 28.

Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(3):147-172. PMID: 22422631 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22422631.

Sawaya GF, Kulasingam S, Denberg TD, Qaseem A; Clinical Guidelines Committee of American College of Physicians. Cervical cancer screening in average-risk women: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(12):851-859. PMID: 25928075 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25928075.

Sawaya GF, Huchko MJ. Cervical cancer screening. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101(4):743-753. PMID: 28577624 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28577624.

Smith RA, Brooks D, Cokkinides V, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2013: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines, current issues in cancer screening, and new guidance on cervical cancer screening and lung cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(2):88-105. PMID: 23378235 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23378235.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320(7):674-686. PMID: 30140884 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30140884.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.