Anxiety disorders - InDepth

Panic disorder - InDepth; Phobias - InDepth; Panic attacks - InDepth; Post-traumatic stress disorder - InDepth; Obsessive-compulsive disorder - InDepthAn in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of anxiety.

Highlights

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders include:

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Panic disorders and panic attacks

- Agoraphobia

- Specific phobias

- Social anxiety disorder (social phobia)

- Separation anxiety disorder

- Selective mutism

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) no longer classifies obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders. However, because these mental health conditions share some characteristics of anxiety disorders, they are included in this report.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for anxiety disorders depend in part on the specific disorder. General risk factors include:

- Gender. With the exception of OCD, women have twice the risk for most anxiety disorders as men.

- Age. Specific phobias, OCD, and separation anxiety typically show up early in childhood, while social phobia and panic disorder often develop during the teen years. GAD is most often diagnosed during middle age.

- Traumatic Events. Traumatic events can trigger anxiety disorders, particularly PTSD. Phobias can develop from traumatic events or develop for seemingly no apparent reason.

- Genetic Factors. Some anxiety disorders tend to run in families. Genetic factors have been identified for GAD and other related disorders. Many of the genes involved affect the function of serotonin, an important neurotransmitter.

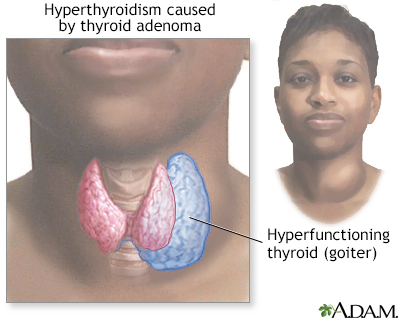

- Medical Conditions. Although causal relationships have not been established, certain medical conditions are associated with panic disorder. They include hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid), asthma, long-term (chronic) obstructive pulmonary disorder, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Changes to Diagnoses of Anxiety Disorders

In 2013, APA released the 5th edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Changes to anxiety disorders include:

- The APA no longer classifies OCD and PTSD as anxiety disorders. OCD is now classified together with other disorders that have obsessive-compulsive features in a new category called obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (OCRD). PTSD is comprised within a larger category called trauma and stressor-related disorders.

- Agoraphobia is no longer a subtype of phobia. The APA now considers specific phobias and agoraphobia as two different types of anxiety disorders.

- Selective mutism, which typically affects children, is now classified as an anxiety disorder. Changes have been made to the description of separation anxiety to reflect that this disorder can affect adults as well as children.

Introduction

Fear and stress reactions are essential for human survival. In a healthy individual, fear is a normal and often a beneficial reaction to a stressful situation.

An anxiety disorder, however, involves an excessive or disproportionate fear response. The anxiety can be triggered even in the absence of an actual threat or can persist even after the threat is removed. Its manifestations include feelings of apprehension, uncertainty, or fear of a potential threat, together with physical symptoms like palpitations, chest tightness, or sweating. The word is derived from the Latin, angere, which means to choke or strangle.

Anxiety disorders are classified according to specific symptoms and behaviors. Types of anxiety disorders include:

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Panic disorder and panic attacks

- Agoraphobia

- Specific phobias

- Social anxiety disorder (social phobia)

- Separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism (which typically although not exclusively occur in children)

The American Psychiatric Association no longer classifies obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders. However, because these mental health conditions share some characteristics of anxiety disorders, they are included in this report.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

GAD is the most common anxiety disorder. It affects about 5% of Americans over the course of their lifetimes. It is characterized by:

- A more-or-less constant state of worry and anxiety, which is out of proportion to the level of actual stress or threat in one's life.

- The anxiety occurs on most days during a period of more than 6 months despite the lack of an obvious or specific stressor.

- People with GAD may experience physical symptoms (such as gastrointestinal complaints) in addition to, or even in place of, mental worries.

- People with GAD tend to be unsure of themselves, overly perfectionist, and conforming.

A diagnosis of GAD is made if three or more of the following symptoms are present (only one for children) on most days for 6 months:

- Being on edge or very restless

- Feeling tired

- Having difficulty concentrating

- Being irritable

- Having muscle tension

- Experiencing disturbed sleep (difficulty falling or staying asleep, having restless or unsatisfying sleep)

People with GAD often have accompanying symptoms such as sweating, nausea, diarrhea, and an extreme startle response. They may also have other health conditions associated with stress such as irritable bowel syndrome and headaches. It is very common for GAD to occur along with another type of anxiety disorder or depression disorder.

Panic Disorder and Panic Attacks

Panic disorder is characterized by periodic attacks of extreme anxiety or terror (panic attacks).

Panic attacks can occur in nearly every anxiety disorder, not just panic disorder. A person may be in a calm state prior to the attack, or they may be feeling anxious. Panic attacks can be either:

- Unexpected. Resulting "out of the blue" from no obvious cue or trigger.

- Expected. Resulting from a situation that typically provokes such attacks.

Panic attacks usually last a few minutes and are accompanied by an intense surge of fear and physical discomfort. A panic attack may also be accompanied by the following symptoms:

- Rapid heartbeat or pounding heart

- Sweating

- Shakiness

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling of being choked or smothered

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Nausea

- Feelings of unreality

- Numbness

- Either hot flashes or chills

- Chest pain

- Fear of losing control or "going crazy"

- Fear of dying

Frequency of attacks can vary widely. Some people have frequent attacks (for example, every week) that occur for months; others may have clusters of daily attacks followed by weeks or months of remission.

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is described as fear of being in public places or open areas. The term comes from the Greek word agora, meaning outdoor marketplace.

In its severest form, agoraphobia is characterized by a paralyzing terror of being in places or situations from which the individual feels there is neither escape nor accessible help in case of an attack. Consequently, people with agoraphobia confine themselves to places in which they feel safe, usually at home.

People with agoraphobia often make complicated plans in order to avoid confronting feared situations and places. About 30% to 50% of people with agoraphobia experience panic disorder and panic attacks. However, the American Psychiatric Association now classifies agoraphobia as a separate and distinct anxiety disorder.

Specific Phobias and Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia)

Phobias, manifested by overwhelming and irrational fears, are a common type of anxiety disorder.

Specific Phobias

Specific phobias (formerly simple phobias) are an irrational fear of specific objects or situations that is out of proportion to the actual danger posed. Specific phobias are very common.

The most common specific phobias are fear of animals (usually spiders, snakes, or mice), flying (pterygophobia), heights (acrophobia), water, injections, public transportation, confined spaces (claustrophobia), dentists (odontiatophobia), storms, tunnels, and bridges. Sometimes specific phobias develop because of a traumatic event. Other times, there does not seem to be any explanation for why they arise. Specific phobias can begin during childhood or in adulthood.

When confronting the object or situation, the phobic person experiences feelings of panic, sweating, avoidance behavior, difficulty breathing, and a rapid heartbeat. Children may express their fear through crying, tantrums, freezing, and clinging. Most phobic adults are aware their fears are unreasonable and irrational, but often overestimate the danger involved in the feared situation. In fact, even thinking about the phobic object or situation can trigger intense anxiety.

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety disorder, also known as social phobia, is an intense fear of social situations and being publicly scrutinized and humiliated by others. It is manifested by extreme shyness and discomfort in social settings. This phobia often leads people to avoid social situations and social interactions, such as eating in public, giving a speech, or meeting unfamiliar people.

Social anxiety disorder is much more than shyness. People with social anxiety disorder fear that they will act in ways that will cause people to judge them negatively. They worry excessively that their actions will cause them to be embarrassed or, that they may offend others. They fear that people will think they are anxious, weak, crazy, stupid, boring, dirty, or unlikeable.

Due to their intense fears and anxieties of social situations, people with this disorder will often seek employment that requires little person-to-person contact. Accompanying mental health disorders are common. They include substance abuse, depression, body dysmorphic disorder, and bipolar disorder.

Separation Anxiety Disorder and Selective Mutism

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety disorder almost always occurs in children, although it can also occur in adults. It is suspected in children who are excessively anxious about separation from important family members or from home. For a diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder, the child should also exhibit at least three of the following symptoms for at least 4 weeks:

- Extreme distress from either anticipating or actually being away from home or being separated from a parent or other loved one

- Extreme worry about losing or about possible harm befalling a loved one

- Intense worry about getting lost, being kidnapped, or otherwise separated

- Frequent refusal to go to school or to sleep away from home

- Physical symptoms such as headache, stomach ache, or even vomiting, when faced with separation

Separation anxiety often disappears as the child grows older, but if not addressed, it may lead to panic disorder, agoraphobia, or other anxiety disorders.

Selective Mutism

Children with selective mutism are capable of speech but do not talk in social situations due to their intense social anxiety. These children will usually speak normally when inside the home and in the presence of immediate family members. Selective mutism is a relatively rare childhood anxiety disorder.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

OCD is a condition marked by unwanted intrusive and repeated thoughts (obsessions) and behaviors (compulsions):

- Obsessions are recurrent or persistent mental images, thoughts, or ideas. The obsessive thoughts or images can range from mundane worries about whether one has locked a door to bizarre and frightening fantasies of behaving violently toward a loved one.

- Compulsive behaviors are repetitive, rigid, and self-directed routines that are intended to prevent the manifestation of an associated obsession. Such compulsive acts might include repetitive checking for locked doors or unlit stove burners or making calls to loved ones at frequent intervals to be sure they are safe. Some people are compelled to wash their hands every few minutes or to spend inordinate amounts of time cleaning their surroundings in order to subdue the fear of contagion.

A feature of this disorder is an inflated sense of responsibility, in which the person's thoughts center on possible dangers and an urgent need to do something about them. Although people with OCD recognize that the obsessive thoughts and ritualized behavior patterns are senseless and excessive, they cannot stop them. OCD is technically not an anxiety disorder, but it often accompanies depression, eating disorders, or other disorders with anxiety components. Some people find that their symptoms subside over time, while others experience a worsening of symptoms.

Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders

The American Psychiatric Association classifies OCD as part of a group of related disorders that include:

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). In BDD, people are obsessed with the belief that they are ugly, or part of their body is abnormally shaped.

- Hoarding Disorder. People with hoarding disorder excessively accumulate possessions and have difficulty discarding them, regardless of their actual value.

- Trichotillomania. People with trichotillomania repeatedly pull their hair out, leaving bald patches.

- Excoriation Disorder. People with excoriation disorder obsessively pick at their skin.

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality

OCD should not be confused with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, which defines certain character traits (being a perfectionist, excessively conscientious, morally rigid, or preoccupied with rules and order). These traits do not necessarily occur in people with OCD.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD is a severe, persistent emotional reaction to a traumatic event that severely impairs one's life. PTSD used to be classified as an anxiety disorder. The American Psychiatric Association now classifies PTSD under a category called Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders.

PTSD is triggered by experiencing or witnessing violent, life-threatening, or traumatic events. It can also occur from learning that traumatic events occurred to a close family member or friend. Such events include, but are not limited to, sexual assaults, accidents, military combat, natural disasters (such as earthquakes), or unexpected deaths of loved ones.

Symptoms of PTSD may begin up to 3 months after the trauma or can develop months or years later. Symptoms can include:

- Re-experiencing. People persistently re-experience the trauma in at least one of the following ways: in recurrent images, thoughts, flashbacks, dreams, or feelings of distress at situations that remind them of the traumatic event. Children may engage in play, in which traumatic events are enacted repeatedly.

- Avoidance. People may avoid reminders of the event, such as thoughts, people, places, objects, or any other factors that trigger recollection.

- Negative and Distorted Thoughts. People tend to have an emotional numbness, a sense of being in a daze or of losing contact with their own identity or even external reality. They may be unable to remember important aspects of the event. They may also have persistent negative feelings about themselves and the world, and feel estranged from those around them.

- Increased Arousal. This includes symptoms of anxiety or heightened awareness of danger (sleeplessness, irritability, being easily startled, or becoming overly vigilant to unknown dangers).

Causes

Anxiety disorders are most likely caused by a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Most people with these disorders seem to have a biological vulnerability to stress, making them more susceptible to environmental stimuli than the rest of the population.

Biochemical Factors

Studies suggest that an imbalance of certain neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) may contribute to anxiety disorders. The neurotransmitters targeted in anxiety disorders are gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. Serotonin appears to be specifically important in feelings of well-being, and deficiencies are highly related to anxiety and depression. Stress hormones such as cortisol also play a role.

Brain Structure Factors

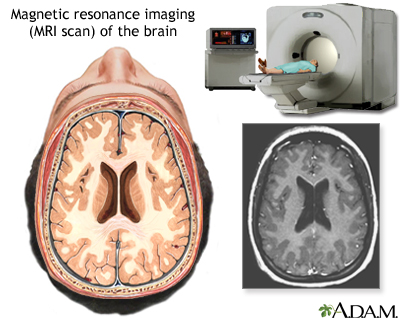

Studies using imaging techniques, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have helped to identify different areas of the brain associated with anxiety responses.

An MRI of the brain creates a detailed image of the complex structures in the brain. An MRI can give a three-dimensional depiction of the brain, making location of problems such as tumors or aneurysms more precise.

In particular, research has focused on changes in the amygdala, which is sometimes referred to as the "fear center." This part of the brain regulates fear, memory, and emotion and coordinates these resources with heart rate, blood pressure, and other physical responses to stressful events. Some evidence suggests that the amygdala in people with anxiety disorders is highly sensitive to new or unfamiliar situations and reacts with a high stress response.

Genetic Factors

Many people with panic disorder and GAD have close relatives with these disorders.

OCD is also strongly related to a family history of the disorder. Close relatives of people with OCD are up to 9 times more likely to develop OCD themselves. Researchers are studying specific genetic factors that might contribute to an inherited risk. Of particular interest are genes that regulate the neurotransmitters associated with serotonin and glutamate.

Risk Factors

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric conditions in the United States.

General Risk Factors for Anxiety Disorders

Gender

Women are generally more likely to develop anxiety disorders than men. They have twice the risk for GAD.

Age

Separation anxiety and selective mutism tend to show up early in childhood. Social anxiety disorder usually manifests between the ages of 8 to 15 years. Specific phobias often develop during adolescence although they can first emerge in adulthood as well. Panic disorders and panic attacks usually develop when people are in their early 20s. GAD is most commonly diagnosed around middle age; older adults also often experience this condition. Children and adolescents who have an anxiety disorder are at risk of later developing other anxiety disorders, depression, and substance abuse.

Personality Factors

Certain personality traits may indicate higher or lower risk for future anxiety disorders. For example, research suggests that extremely shy children and those likely to be the target of bullies are at higher risk for developing anxiety disorders later in life. Children who cannot tolerate uncertainty tend to be worriers, a major predictor of generalized anxiety. In fact, such traits may be biologically based and due to a hypersensitive amygdala -- the "fear center" in the brain.

Family History and Dynamics

Anxiety disorders tend to run in families. Genetic factors may play a role in some cases, but family dynamics and psychological influences are also often at work. Several studies show a strong correlation between a parent's fears and those of the offspring. Although an inherited trait may be present, some researchers believe that many children can "learn" fears and phobias, just by observing a parent or loved one's phobic or fearful reaction to an event.

Social Factors

Several studies have reported a significant increase in anxiety levels in children and college students in recent decades. In several studies, anxiety was associated with a lack of social connections and a sense of a more threatening environment. It also appears that more socially alienated populations have higher levels of anxiety.

Traumatic Events

Traumatic events can trigger anxiety disorders, such as in individuals who are susceptible to them because of psychological, genetic, or biochemical factors. Specific traumatic events in childhood, particularly those that threaten family integrity, such as spousal or child abuse, can also lead to other anxiety and emotional disorders. Some types of specific phobias, for instance of spiders or snakes, may be triggered and perpetuated after a single traumatic exposure.

Medical Conditions

Although causal relationships have not been established, certain medical conditions are associated with increased risk of panic disorder. They include hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and irritable bowel syndrome. Women often report experiencing symptoms of anxiety and panic attacks during the transition to menopause (perimenopause), which may be related to fluctuating hormone levels.

Specific Risk Factors for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

GAD affects more women than men. It most commonly occurs around age 30, but can occur earlier or later in life. Depression commonly accompanies GAD, as well as other anxiety disorders.

Specific Risk Factors for Panic Disorder and Panic Attacks

Panic disorder and panic attacks are more common in women than men. These conditions usually develop between the ages of 20 to 24 years. People with these disorders have increased risk for other mental health disorders including depression, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, and other anxiety disorders. They also have an increased risk for suicide.

Specific Risk Factors for Phobias and Social Anxiety Disorder

Specific phobias are more common in females and often emerge during the teenage years. People with phobias are at increased risk for developing other mental health disorders, and have an increased risk for suicide attempts.

Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) usually develops between the ages of 8 to 15 years. In children, bullying may trigger social anxiety disorder. It is rare for social anxiety disorder to first develop in adulthood. When it does, it is usually the result of a particularly stressful or humiliating event. Women are more likely to develop social phobia than men, although equal numbers of men and women seek treatment for it. Most people seeking treatment have had symptoms for at least 10 years.

Complications

All types of anxiety disorders can be very debilitating and seriously affect a person's quality of life.

Accompanying Mental Health Conditions

Depression

Depression is very common in people with an anxiety disorder, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the two conditions. Both can have symptoms of anxiety, agitation, insomnia, and poor concentration. The combination of depression and anxiety is a major risk factor for both substance abuse and suicide.

Bipolar Disorder

Symptoms of panic disorder are very common in people with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, anxiety worsens bipolar disorder.

Substance Abuse

People who have anxiety disorders, depression, or bipolar disorder are at high risk for alcohol use disorder, smoking, and other forms of addiction, which may be a form of self-medication.

Eating Disorders

Many people with anxiety disorders have eating disorders, and the reverse is also true. It is not clear if anxiety disorders, particularly OCD, cause eating disorders, increase susceptibility to them, or share common biologic causes.

Increased Risk for Suicide

Panic disorders and PTSD are associated with increased risk for suicidal thoughts. Social phobias and OCD also increase the risk of suicide. If a person has an anxiety disorder and a mood disorders (such as depression), the risk for suicide is even higher.

Effects on Work, School, and Relationships

Anxiety disorders can have devastating effects on work and relationships. People with anxiety disorders may turn down promotions or avoid business meetings so as to not have to deal with fears of performance pressures or social interactions. They may have challenges making new friends or dating. In children, anxiety disorders can have a significant negative impact on academic performance as well as participation in social activities.

Anxiety disorders can be very isolating. It is often difficult for people with anxiety disorders to explain to family and friends what it is like to live with the condition.

Physical Effects of Anxiety Disorders in Adults

Anxiety disorders are associated with many different physical illnesses.

Heart Disease

Anxiety has been associated with several heart risk factors, including unhealthy cholesterol levels, thicker blood vessels, and high blood pressure. Both anxiety and depression are associated with a poorer response to treatment in heart patients, including a worse outcome after heart surgery. The role of anxiety disorders in triggering serious cardiac events remains unclear.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Anxiety frequently accompanies gastrointestinal conditions, particularly irritable bowel syndrome.

Pain

Chronic pain and muscle tension are common in people with anxiety disorders. Both tension and migraine headaches are also associated with anxiety disorders.

Respiratory Problems

Studies report an association between anxiety in people with obstructive lung conditions (such as asthma, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis) and more frequent relapses.

Obesity

Anxiety disorders may lead to obesity, and the reverse may also be true.

Allergic Conditions

Anxiety disorders are associated with numerous allergic conditions including hay fever, eczema, hives, food allergies, and conjunctivitis.

Other Conditions

People with obsessive-compulsive related disorders can experience skin problems from excessive washing, injuries from repetitive physical acts and skin picking, and hair loss from repeated hair pulling (disorder known as trichotillomania).

Physical Effects of Anxiety Disorders in Children

Children with anxiety disorders often suffer from recurrent stomach aches. Anxiety is associated with a higher risk for sleep disorders in children, such as frequent nightmares, restless legs syndrome, and bruxism (the grinding and gnashing of teeth during sleep).

Diagnosis

A doctor diagnoses an anxiety disorder based on specific symptoms, how often they occur, how long they have lasted, and how significantly they interfere with daily functioning.

The doctor may ask about emotional symptoms, such as:

- Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge

- Feeling irritable, annoyed, or angry

- Feeling worried a lot about different things

- Not being able to stop or control worrying

- Having trouble relaxing

- Being so restless it is difficult to sit still

- Feeling afraid something awful may happen

The doctor may also ask about physical symptoms, such as:

- Muscle trembling or shaking

- Pounding heart

- Sweating

- Nausea or stomach aches

- Feeling of choking or suffocation

- Headaches

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Numbness or tingling sensations

- Chills or heat sensations

Because anxiety accompanies so many medical conditions, some serious, it is extremely important for the doctor to make sure that an anxiety attack is not being caused by an underlying medical problem, medication side effects, or substance abuse. The doctor will perform a physical examination and ask about the person's medical and personal history.

The person should describe any occurrence of anxiety disorders or depression in the family and mention any other contributing factors, such as excessive caffeine use, recent life changes, or stressful events.

It is very important to be honest with your doctor about all conditions, including excessive drinking, substance abuse, or other psychological or mood states that might contribute to, or result from, the anxiety disorder.

Anxiety disorders need to be distinguished from other mental health conditions. Anxiety disorders also often occur along with other mental health conditions such as depression, eating disorders, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Other Conditions with Similar Symptoms

People with anxiety disorders are more likely to see a family doctor before a mental health specialist, since their symptoms are often physical. Symptoms can include muscle tension, trembling, twitching, aching, soreness, cold and clammy hands, dry mouth, sweating, nausea or diarrhea, or urinary frequency. Anxiety attacks can mimic or accompany nearly every acute disorder of the heart or lungs, including heart attacks, heart arrhythmia, and angina (chest pain). In fact, nearly all individuals with panic disorders and panic attacks are convinced that their symptoms are physical and possibly life-threatening.

Heart Problems

Some people who enter the emergency room with chest pain, and who have a low-to-moderate risk for a heart attack, are actually suffering from panic attacks:

- Women who are having an actual heart attack or acute heart problem are much more likely to be misdiagnosed as having an anxiety attack than are men with similar symptoms.

- Mitral valve prolapse, a common and usually mild heart problem, can have anxiety symptoms that are nearly identical to those of panic disorder. The two conditions, in fact, sometimes occur together.

Mitral valve prolapse is a disorder in which the mitral valve does not close properly when the heart contracts. When the valve does not close properly it allows blood to backflow into the left atrium. Some symptoms can include palpitations, chest pain, difficulty breathing after exertion, fatigue, cough, and shortness of breath while lying down.

- People with a heart-rhythm disturbance called paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia may have many of the same symptoms as those with panic attacks.

Asthma

Asthma attacks and panic attacks have similar symptoms and can also coexist.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid gland) can cause many of the same symptoms of anxiety disorders.

Other Medical Conditions

Anxiety-like symptoms are seen in many other medical problems, including hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and seizure disorders. Women can also experience anxiety attacks with intense hot flashes during menopause.

Medication Side Effects

Many drugs, including some for high blood pressure, diabetes, and thyroid disorders, can produce symptoms of anxiety. Withdrawal from certain drugs, often those used to treat sleep disorders or anxiety, can also precipitate anxiety reactions.

Substance Abuse

People with anxiety disorders often drink alcohol or abuse drugs in order to conceal or eliminate symptoms, but substance abuse and dependency can also cause anxiety. In addition, withdrawal from alcohol can produce physiologic symptoms similar to panic attacks. Clinicians often have difficulty determining whether alcohol use disorder or anxiety is the primary disorder. Overuse of caffeine or abuse of amphetamines can cause symptoms resembling a panic attack.

Screening Tests

Clinicians use various screening tests to determine the causes, type, severity, and frequency of anxiety. Such tests include the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Social Phobia Inventory, the Penn State Worry Questionnaire, the GAD Scale, and the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

Treatment

The standard approach to treating most anxiety disorders is a combination of talk therapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and an antidepressant medication. A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) is typically the first choice, with the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Effexor, generic) being an alternative. If people do not respond to these drugs, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may be helpful. Benzodiazepines may be recommended for people who are not helped by antidepressants or who need help rapidly (antidepressants take several weeks to be effective). A healthy lifestyle that includes exercise, adequate rest, and good nutrition can also help to reduce the impact of anxiety.

Treatment Options for Specific Anxiety Disorders | ||

Anxiety Disorder | Medications | Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Other Non-Drug Therapies |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and buspirone are helpful but have varying side effects. Investigational drugs include pregabalin and other anticonvulsants. | Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or anxiety management therapy. Anxiety management therapy involves education, relaxation training, and exposure to anxiety-provoking stimuli but does not include cognitive restructuring. |

Panic Attacks | SSRIs are treatment of choice. If people do not respond to SSRIs, short-term treatment with a benzodiazepine may be used, or people may switch to another type of antidepressant such as venlafaxine or tricyclics. | CBT, provided in 12 to 16 sessions over 3 to 4 months, focuses on recreating fear symptoms and helping people change their response to them. |

Social Anxiety Disorder | SSRIs or venlafaxine are first-line drug treatments. Benzodiazepines may help people who do not respond to these antidepressants. Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica) are being investigated. | CBT can help improve symptoms after 6 to 12 weeks. |

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | SSRIs are the first choice for adults. Clomipramine (a tricyclic antidepressant) is an alternative for adult people who do not respond to SSRIs. For children, SSRIs do not seem to work as well for OCD as for other types of anxiety disorders. | CBT is the first treatment choice for children. For adults, either CBT or drug therapy may be offered as initial treatment. CBT techniques focus on exposure and response prevention (ERP). |

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | Antidepressants, particularly SSRIs (sertraline and paroxetine approved for PTSD). An atypical antipsychotic may be added to an antidepressant for people who do not respond to an SSRI alone. | Trauma-focused psychological treatments include cognitive-behavioral therapy, exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. |

Note: For anxiety disorders in adults, the most effective treatments are usually combinations of drugs and CBT techniques. For children, CBT is usually the first treatment. | ||

Medications

SSRIs, or the SNRI venlafaxine (Effexor, generic), are the primary first-line treatment for anxiety disorders. For people who are not helped by these drugs or who need help rapidly, benzodiazepines may be prescribed, either alone or in combination with an antidepressant. Other types of antidepressants, including TCAs, may also be used to treat people with severe or chronic forms of anxiety disorders.

Drug therapies for anxiety disorders work best in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy or some other form of psychotherapy.

Antidepressants

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs include:

- Fluoxetine (Prozac, generic)

- Sertraline (Zoloft, generic)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, generic)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox, generic)

- Citalopram (Celexa, generic)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro, generic)

SSRI side effects are generally mild but may include dry mouth, upset stomach, and agitation. Specific side effects vary depending on the drug, and on the individual's reaction to it. Sexual dysfunction, including lowered sex drive, and weight gain are common side effects of many antidepressants. Older people taking these drugs should take the lowest effective dose possible, and those with heart problems should be monitored closely.

Antidepressants may raise the risk for suicidality (suicidal thoughts and behavior) in young people, particularly those ages 18 to 24 years. Both adults and children who are treated with SSRIs should be carefully monitored for any worsening of depressive symptoms or changes in behavior. This is important during the first few months of antidepressant treatment.

Paroxetine has been linked to heart-related birth defects when used during the first trimester of pregnancy. It should not be taken by women who are pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant. Other SSRIs are generally considered safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding. The FDA has recently updated the public on the use of SSRIs by pregnant women and the potential for development of a rare heart and lung condition called persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). Due to conflicting data, the FDA advises health care providers to continue their current practice of treating depression in pregnancy. Still, women who are pregnant or who are considering becoming pregnant should discuss the potential risks of these drugs with their doctors before just stopping the medicine.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

SNRIs are known as dual action inhibitors because they work on two neurotransmitters -- norepinephrine and serotonin. Venlafaxine (Effexor. generic) is an SNRI that is approved for treatment of GAD, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder, Duloxetine (Cymbalta, generic) is approved for treatment of GAD. Both of these SNRIs are approved for adults but not for children.

As with SSRIs, venlafaxine may impair sexual function. Venlafaxine can increase blood pressure and heart rate and should be used with caution in people with high blood pressure or heart disease. Some people report severe withdrawal symptoms, including dizziness and nausea. This drug has a serious risk for overdose. Venlafaxine use should be carefully considered during the last trimester of pregnancy because the drug can cause complications in newborn infants.

Duloxetine's side effects are generally mild and include dry mouth, nausea, and sleepiness. People with narrow-angle glaucoma or people with liver or kidney diseases should not take duloxetine. Because duloxetine can cause liver damage, people who drink large quantities of alcoholic beverages should not take it.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclics are an older type of antidepressant. Tricyclics used for treatment of anxiety disorder include:

- Imipramine (Tofranil, generic), for GAD and panic disorder

- Nortriptyline (Pamelor, generic), for panic disorder

- Desipramine (Norpramin, generic), for panic disorder

- Clomipramine (Anafranil, generic), for OCD. Clomipramine is approved specifically for OCD, but because of its severe side effects it is usually used only if SSRIs have failed to help.

Side effects of TCAs include sleep disturbance, abrupt reduction in blood pressure upon standing, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and mental disturbance. Older people and those with a history of seizures, cardiac problems, closed-angle glaucoma, and urinary retention or obstruction should be closely supervised when taking tricyclics.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are effective medications for most anxiety disorders and have been a standard treatment for years. However, their long-term daily use is associated with a risk for dependency and abuse. Therefore, they have been replaced in most cases by SSRIs and other newer antidepressants.

For anxiety disorders, benzodiazepines are most often used to treat panic disorder, and are sometimes used for social anxiety disorder and GAD. These drugs include:

- Alprazolam (Xanax, generic)

- Clonazepam (Klonopin, generic)

- Lorazepam (Ativan, generic)

Benzodiazepines can have many side effects, which are generally associated with long-term (chronic) use. The most common are daytime drowsiness and a hung-over feeling. In rare cases, they can cause agitation. They may worsen respiratory problems. Benzodiazepines are potentially dangerous when used in combination with alcohol or certain pain medications. Overdoses can be serious, although they are very rarely fatal.

Older people are more susceptible to side effects and should usually start at half the dose prescribed for younger people. These drugs increase the risk of falling, which can increase the risk for hip fracture in older people. Benzodiazepines taken during pregnancy are associated with birth defects (such as cleft palate). These drugs should not be used by pregnant women or by nursing mothers.

Loss of Effectiveness and Dependence

Eventually these drugs can lose their effectiveness with continued use at the same dosage (this is called tolerance). As a result, people may want to increase their dosage to prevent anxiety. This causes dependency, which can occur after taking these drugs for several weeks.

Withdrawal and its Treatments

Withdrawal symptoms can occur in people who suddenly stop taking benzodiazepines. Symptoms can be very severe, even after taking benzodiazepines for only 4 weeks. Symptoms include sleep disturbance and anxiety, which can develop within hours or days after stopping the medication. Some people experience stomach distress, sweating, and insomnia, which can last 1 to 3 weeks. Suddenly stopping treatment with benzodiazepines may also cause seizures. The longer the drugs are taken and the higher their dose, the more severe withdrawal symptoms can become. Tapering off gradually is the best approach to stop taking these drugs. Certain medications (such as anti-seizure drugs, antidepressants, and buspirone) may help with withdrawal.

Azapirones (Buspirone)

Azapirones, such as buspirone (BuSpar, generic), act on serotonin receptors called 5-HT(1A). Buspirone appears to work as well as a benzodiazepine for treating GAD. It usually takes several days to weeks for the drug to be fully effective. It is not useful against panic attacks.

Buspirone tends to have less pronounced side effects than benzodiazepines and no withdrawal effects, even when the drug is discontinued quickly. Common side effects include dizziness, drowsiness, and nausea. Buspirone should not be used with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Unlike the benzodiazepines, buspirone is not addictive, even with long-term use, so it may be particularly helpful for the people whose anxiety disorder coexists with alcoholism or drug abuse.

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers, including propranolol (Inderal, generic) and atenolol (Tenormin, generic), block the action of some chemicals in the body that make the heart beat faster. They affect only some of the physiologic symptoms of anxiety (such as rapid heart rate, shaking, trembling, and blushing) and are most helpful for phobias, particularly performance anxiety. They may be taken before entering a situation where anxiety symptoms tend to occur. Beta blockers are less effective for other forms of anxiety.

Anticonvulsants (Antiseizure Drugs)

Pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin, generic) are drugs used to treat seizures and other conditions. Researchers are investigating whether these drugs may be useful for certain anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety disorder and general anxiety disorder. However, their exact role in the treatment of anxiety disorders is not clear.

Atypical Antipsychotics

Atypical antipsychotics are approved for treating schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and, in some cases, major depressive disorder. They may sometimes be used "off-label" for treating severe cases of OCD or PTSD. However, atypical antipsychotics (particularly olanzapine) can have many severe side effects. These include weight gain and increased high blood sugar levels, which can increase the risk for diabetes. Antipsychotic drugs are also associated with increased risk for movement disorders called extrapyramidal symptoms.

The American Psychiatric Association advises that while atypical antipsychotics are appropriate for treating conditions such as pediatric schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, they should not be routinely prescribed to children and adolescents for non-psychotic diagnoses.

Psychotherapy and Other Treatments

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

The goal of CBT is to regain control of reactions to stress and stimuli, thus reducing the feeling of helplessness that often accompanies anxiety disorders. CBT works on the principle that the thoughts that produce and maintain anxiety can be recognized and altered using various techniques that change behavioral responses and eliminate the anxiety reaction.

CBT and medication are each effective alone but many studies have shown that a combination of CBT and medication works best for treating anxiety disorders. A combination of CBT and medication is particularly effective for children and adolescents with GAD, separation anxiety, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), and OCD.

Studies suggest that CBT is also helpful for people who have additional conditions, such as depression, a second anxiety disorder, or alcohol use disorder. (However, it may take longer to achieve a successful outcome in such cases.)

Both individual and group treatments work well. However, people with social phobia do better in individual sessions.

Anxiety disorders are long-term (chronic) and recurrence is common, even after successful short-term therapy. Some people with anxiety disorders may require long-term or intensive therapy of at least a year or 50 sessions. Medications, then, are also generally recommended for most people.

Basic Cognitive Therapy Techniques

Treatment usually takes about 12 to 20 weeks. The essential goal of cognitive therapy is to understand the realities of an anxiety-provoking situation and to respond to reality with new actions based on reasonable expectations.

- First, the person must learn how to recognize anxious reactions and thoughts as they occur. One way of accomplishing this is by keeping a daily diary that reports the occurrences of anxiety attacks and any thoughts and events associated with them. A person with OCD, for instance, may record repetitive thoughts.

- These entrenched and automatic reactions and thoughts must be challenged and understood. Using the OCD example, one approach is to record and play back the words of the repetitive thoughts, overexposing the person to the thoughts and reducing their effect. For people with GAD, CBT targets their intolerance of uncertainty and helps them develop methods to cope with it.

- People are usually given behavioral homework assignments to help them change their reactions. For example, a person with generalized social phobia may be asked to buy an item and then return it the next day. As people perform these actions, they learn to recognize fears and thoughts triggered by similar events and to understand that these fears are unrealistic.

- As the person continues with self-observation, they begin to perceive the false assumptions that underlie the anxiety. For example, people with OCD may learn to recognize that their heightened sense of responsibility for preventing harm in non-threatening situations is neither necessary nor useful.

- At that point, the person can begin substituting new ways of coping with the feared objects and situations.

Systematic Desensitization

Systematic desensitization is a specific technique that breaks the link between the anxiety-provoking stimulus and the anxiety response. This treatment requires the person to gradually confront the object of fear. There are three main elements to the process:

- Relaxation training

- A list composed by the person that prioritizes anxiety-inducing situations by degree of fear

- The desensitization procedure itself, confronting each item on the list, starting with the least stressful, while in a relaxed state.

This treatment is effective for simple phobias, social phobias, agoraphobia, and post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Exposure and Response Treatment

Exposure treatment purposefully generates anxiety by exposing the person repeatedly to the feared object or situation, either literally or using imagination and visualization. It uses the most fearful stimulus first. (This differs from the desensitization process because it does not involve relaxation or a gradual approach to the source of anxiety.)

Exposure treatments are usually known as either flooding or graduated exposure:

- Flooding exposes the person to the anxiety-producing stimulus for as long as 1 to 2 hours.

- Graduated exposure gives the person a greater degree of control over the length and frequency of exposures.

In both cases, the person experiences the anxiety over and over until the stimulating event eventually loses its effect. Combining exposure with standard cognitive therapy may be particularly beneficial. This approach has helped certain people in most anxiety disorder categories, including PTSD. However, exposure therapy may not be appropriate in all cases. New exposure therapy techniques involving virtual reality technology will require more studies.

Modeling Treatment

Phobias can often be treated with modeling or "guided mastery" techniques in which the therapist models how the person can successfully encounter and interact with the feared object. The person observes this event and tries to learn how to behave in a comparable manner.

Anxiety Management Therapy

Anxiety management therapy is sometimes used as an alternative to CBT for GAD. It involves patient education, relaxation training, and exposure to anxiety-provoking stimuli but does not include exercises in cognitive retraining.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR therapy involves the person focusing on eye movements or other external stimuli as directed by the therapist while at the same time recalling the distressing images or situations. EMDR therapy is among the strategies recommended by the American Psychological Association for the treatment of PTSD.

Other Forms of Psychotherapy

Other forms of psychotherapy, commonly called emotion-based psychotherapy (EBT), psychodynamic therapy, or "talk" therapy, deal more with the roots of anxiety and usually, although not always, require longer treatments. All work is done during the sessions. Some research indicates that such therapies might be more useful for generalized anxiety, which may require more sustained work to process and recover from early traumas and fears. Studies suggest that although emotion-based psychotherapies are not as effective as CBT in treating panic disorders, people tend to stay longer in EBT than in CBT. Some doctors recommend adding elements of EBT to the usual CBT and medication treatments.

Relaxation Training and Related Therapies

Relaxation Training

Relaxation techniques use muscle relaxation and mental visualization to help focus attention towards a calming feeling. Some people find meditation helpful.

Breathing Retraining

Breathing retraining techniques may help reduce the physical effects of anxiety. For example, hyperventilation is one of the primary physical manifestations of panic disorders. This involves rapid, tense breathing, resulting in chest pain, dizziness, tingling of the mouth and fingers, muscle cramps, and even fainting. By practicing measured, controlled breathing at the onset of a panic attack, people may be able to prevent full attacks.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback uses special sensors that allow people to recognize anxiety states by changes in specific physical functions, such as changes in pulse rate, skin temperatures, and muscle tone. Eventually, people feel like they can control these changes, which in turn helps relieve anxiety. While commonly used, there are not many rigorous studies showing that biofeedback helps people reduce or eliminate their symptoms over the long term.

Psychological Therapies for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Several types of psychological treatments have been designed specifically for treating people with PTSD. These approaches include a special type of CBT known as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TFCBT), and a psychotherapy treatment called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).

With TFCBT, people are taught stress management skills. The therapist helps the person develop a narrative (verbal, written, or artistic) about the traumatic event. People may be exposed to reminders about the trauma and are taught how to cope with future reminders. Through the process, the person learns how to reprocess their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

With EMDR, the person focuses on remembering the traumatic experience while visually following the rhythmic movement of the therapist's fingers. The person recounts to the therapist what memories have been provoked during the exercise. EMDR may help people recall details and sensations that they had blocked out. Through this breakthrough, people learn how to regain emotional control.

Researchers are investigating other forms of treatment for PTSD including yoga, acupuncture, and animal-assisted therapy.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your provider before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Some people use aromatherapy as a relaxation aid, although there is no clear evidence that it works. Aromatherapy is in general safe, but some plant extracts in these formulas have been linked to skin allergies.

There is no evidence supporting the efficacy of valerian, St. John's wort, or passionflower for treatment of anxiety. The herbal remedy kava has been associated with liver problems and should not be used. Kava can also interact dangerously with medications that are metabolized by the liver.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a surgical approach that involves implanting in the brain a small device similar to a pacemaker. DBS may be used in some cases of OCD that are not responding to conventional therapy.

The device is similar to other DBS devices used for treating movement disorders like Parkinson disease. It uses four electrodes that are surgically implanted into the brain and connected by wires to a small generator that is implanted near the abdomen or collar bone. The generator delivers precisely controlled electrical pulses to target specific areas of the brain.

Another brain stimulation approach, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), does not involve surgery or implantation. It uses an external machine to generate high-frequency magnetic pulses to target and stimulate areas of the brain. TMS is also being studied as a possible treatment for OCD.

Surgery

A surgical technique called cingulotomy involves interrupting the cingulate gyrus, a bundle of nerve fibers in the front of the brain. It is sometimes used as a last resort for people with severe OCD.

Resources

- National Institute of Mental Health -- www.nimh.nih.gov

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America -- adaa.org

- National Alliance on Mental Illness -- www.nami.org

- Mental Health America -- www.mhanational.org

- The American Psychiatric Association -- www.psychiatry.org

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry -- www.aacap.org

References

American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2020.

Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16(2):77-84. PMID: 22540422 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22540422/.

Bui E, Pollack MH, Kinrys G, Delong H, Vasconcelos e Sá D, Simon NM. The pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 41.

Calkins AW, Bui E, Taylor CT, Pollack MH, LeBeau RT, Simon NM. Anxiety disorders. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 32.

Craske MG, Stein MB. Anxiety. Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3048-3059. PMID: 27349358 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27349358/.

Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128-141. PMID: 26574151 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26574151/.

Dekel S, Gilbertson MW, Orr SP, Rauch SL, Wood NE, Pitman RK. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 34.

DeMartini J, Patel G, Fancher TL. Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(7):ITC49-ITC64. PMID: 30934083 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30934083/.

DeMaso DR, Walter HJ. Psychopharmacology. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 33.

Forman-Hoffman V, Middleton JC, Feltner C, et al. Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review Update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018. PMID: 30204376 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30204376/.

Gottschalk MG, Domschke K. Genetics of generalized anxiety disorder and related traits. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(2):159-168. PMID: 28867940 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28867940/.

Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, American Psychological Association. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am Psychol. 2019;74(5):596-607. PMID: 31305099 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31305099/.

Hamani C, Pilitsis J, Rughani AI, et al. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: systematic review and evidence-based guideline sponsored by the American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) and endorsed by the CNS and American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Neurosurgery. 2014;75(4):327-333. PMID: 25050579 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25050579/.

James AC, James G, Cowdrey FA, Soler A, Choke A. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD004690. PMID: 25692403 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25692403/.

Leichsenring F, Leweke F. Social Anxiety Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2255-2264. PMID: 28591542 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28591542/.

Moreno-Alcázar A, Treen D, Valiente-Gómez A, et al. Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in children and adolescent with post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1750. PMID: 29066991 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29066991/.

Rizzo A, Shilling R. Clinical virtual reality tools to advance the prevention, assessment, and treatment of PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(sup5):1414560. PMID: 29372007 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29372007/.

Rosenberg DR, Chiriboga JA. Anxiety disorders. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 38.

Stewart SE, Lafleur D, Dougherty DD, Wilhelm S, Keuthen NJ, Jenike MA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 33.

Walter HJ, DeMaso DR. Psychosocial assessment and interviewing. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 32.

Review Date: 7/20/2020

Reviewed By: Fred K. Berger, MD, addiction and forensic psychiatrist, Scripps Memorial Hospital, La Jolla, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.