Smoking - InDepth

An in-depth report on the health risks of smoking and how to quit.

Highlights

Overview:

- Tobacco use causes more than 7 million deaths per year worldwide. In the US, tobacco use is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths per year.

- Smokers lose 10 years of life on average from smoking-related illness, including cancers, heart disease, stroke, and COPD.

- About 13.7% of adults in the United States smoke.

- Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States and in the world.

- Heavy smoking (a pack a day) has been on the decline over the past few decades. Smoking cessation programs and smoke-free environments have played a role in the decline.

- Despite this progress, as of 2017, about 5% of people who smoke consumed 24 or more cigarettes a day. Thousands of young people start smoking every day, and the tobacco industry spending on advertising has increased.

- Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia have enacted statewide laws banning smoking in enclosed workplaces, including restaurants and bars.

- In addition to lung and circulatory damage, smoking is associated with several negative health outcomes, including poor pregnancy outcomes (such as birth defects), lower survival rates after diagnosis from prostate cancer, and Alzheimer disease later in life.

Smoking Cessation:

- Quitting smoking can prevent or reverse many smoking-related illnesses.

- Specially tailored online provider programs (WeBREATHe) can encourage clinicians to discuss smoking with children and adolescents.

- Pediatric counseling and interventions are key to stopping smoking before it starts.

- Workplace interventions can help, whether administered through the workplace or other organizations.

In Adults:

- Interventions that combine medicines with behavioral counseling (at least 4 to 8 sessions) are more effective than brief advice or usual care.

- Quitting smoking significantly lowers the risk for surgical complications, including heart problems, lung problems, and poor wound or bone healing. Smoking cessation interventions during the 1 to 2 months before surgery or immediately after surgery may reduce the occurrence of these complications.

- Electronic, online, and computer cessation programs have a small but important impact on cessation rates compared to no intervention or self-help materials. The relatively low cost of electronic interventions makes the approach a good option.

- All forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), such as gum, patch, spray, and tablets, can be effective in promoting smoking cessation. NRT increases the quit rate by 50% to 70% for at least 6 months or longer. Most of the research is focused on adults, but adolescents may also benefit from NRT.

- Although not yet proven on a large scale, using e-cigarettes or nicotine vaporizers (vaping or Juuling) may help some people quit smoking, and is hoped to be less toxic than smoking cigarettes. However, e-cigarettes are increasingly popular among children and adolescents who do not smoke. As of 2019, more than 10% of middle school students and 27% of high school students reported using e-cigarettes. Researchers worry that by creating nicotine addiction in people who are not current smokers, they may serve as gateway products leading to smoked tobacco use. Additionally, the risk due to chemicals in e-cigarettes is not well known. The FDA has announced that it will regulate all electronic nicotine delivery systems in the same way that it regulates tobacco products. Larger-scale studies are necessary. The FDA has also announced it is considering setting maximum nicotine content in cigarettes in order to minimize addictiveness.

Screening:

- In people who have no history of lung cancer, annual low-dose CT screening for lung cancer should be offered. Screening should be performed in current and former smokers who are between the ages of 55 to 74 years, have smoked at least 30 pack-years, and are currently smoking or have quit within the past 15 years.

- Chest x-rays should not be offered as a screening tool as it is not effective.

Introduction

About 13.7% of adults in the United States, currently smoke, according to a 2018 report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Smoking rates are down from 20.9% in 2005.

Heavy smoking (a pack-a-day habit) is also down from a few decades ago. Back in 1965, close to 23% of Americans were heavy smokers. Today, only about 5% smoke 24 cigarettes a day or more. Overall, smokers are reducing the amount of cigarettes smoked per day. California has been especially successful at reducing rates of heavy smoking rates, in part due to smoking cessation programs and smoke-free environments.

In 2018, more than 55% of adults reported attempting to quit smoking in the past year.

These reductions in overall smoking are good news, but smoking is still a big health problem. It kills 480,000 people a year in the United States, accounting for nearly 1 out of every 5 deaths.

Smoking hazards

The addictive effects of the nicotine found in tobacco have been well documented. Nicotine is believed to have an addictive potential comparable to alcohol, cocaine, and morphine. Tobacco and its various components increase the risk of cancer (especially in the lung, mouth, larynx, esophagus, bladder, kidney, pancreas, and cervix), heart attacks and strokes, and chronic lung disease.

The addictive effects of tobacco have been well-documented. Tobacco is considered to be a mood and behavior-altering substance that is abusable. Tobacco is believed to be as potentially addictive as alcohol, cocaine, and morphine. Tobacco and its components increase the risk for cancer (especially in the lung, mouth, larynx, esophagus, bladder, kidney, colon, pancreas, and cervix), heart attacks, strokes, and chronic lung disease.

Smoking in Childhood and Adolescence

Fewer teens are smoking today than in the late 1990s, but the decrease in teen smoking rates has slowed in recent years. In 2019, 31.2% of high school students and 12% of middle school students used some form of tobacco product. Cigarette use has decreased, but use of electronic cigarettes has increased substantially in the United States, from 0.6% of middle school students in 2011 to 10.5% in 2019, and from 1.5% of high school students in 2011 to 27.5% in 2019.

The younger children start smoking, the more likely they will smoke as adults. Smoking can become addictive very quickly. According to the American Cancer Society, the earlier you start smoking, the more likely you are to develop long-term nicotine addiction.

In the past, advertising played a major role in encouraging some teens to smoke. New regulations have made it much more difficult for advertisers to promote smoking to young people. However, scenes that show people smoking, often in a positive way, are still common in movies and television shows. This may be a major influence on the attitude toward smoking in children and adolescents.

Research has found that parents can discourage their children from smoking by:

- Not smoking themselves

- Telling their children they do not approve of smoking

- Closely monitoring their children's television and music-listening habits

- Being home for their kids and providing a structured home life

Doctors can also have a major effect on their young person's smoking habits. However, less than one-half of teenagers say their doctors have ever asked them if they smoke (even though most teen smokers said they would admit to smoking if asked) or given them counseling on how to quit. Counseling may be of particular importance, considering that teens who smoke are more likely to attempt suicide than their non-smoking peers.

The Web-Based Respiratory Education About Tobacco and Health (WeBREATHe) program is an online training program for pediatric providers that can encourage clinicians to discuss smoking with their patients.

Gender, Age, and Ethnicity

Age |

Total |

| 18 to 24 years | 7.8% |

| 25 to 44 years | 16.5% |

| 45 to 64 years | 16.3% |

| 65 years and older | 8.4% |

Men are more likely to smoke than women. In the United States, 15.6% of men and 12.0% of women are current smokers.

While the percentage of adults over age 65 who smoke is lower than the percentage of smokers in other age groups, older adults usually have smoked for a long time (about 40 years) and tend to be heavier smokers, according to the American Lung Association. Because of this, older smokers are more likely to have smoking-related illnesses.

Current cigarette smoking is highest in non-Hispanic American Indians or Alaska Natives and lowest among Asians. Among high school students (under age 18), white people are more likely to smoke cigarettes than Hispanics and African Americans.

Educational Level

People who have not graduated from high school or received their General Education Development (GED) certificate are more likely to smoke than those who attended college. The lowest smoking rates are in people with advanced graduate degrees.

Psychological and Physical Factors

Men and women with mental or physical disorders are about 50% more likely to smoke than people without such illnesses. Factors that can influence smoking include:

- Low self-esteem

- Behavioral problems (in teens)

- Depression

- Schizophrenia

- Physical disabilities

Having depression increases the likelihood that someone will smoke, and decreases their likelihood of quitting. Twice as many adults with depression are current smokers, compared to those without depression. The more severe their depression, the more likely people are to smoke.

Genetic Factors

Evidence strongly supports the idea that genes play a role in a person's dependence on nicotine. Researchers are now targeting specific genes that may be responsible for nicotine dependence. The same genes may be responsible for both nicotine and alcohol dependence.

Economic Factors

Some studies suggest that smoking becomes more widespread when it is cheaper to buy cigarettes. For example, states that have low taxes on cigarettes have a high proportion of smokers. Making it more expensive to smoke may reduce the number of smokers. Education and smoking prevention programs can reduce the number of smokers. However, of revenue gathered by states from tobacco taxes and tobacco industry legal settlements, overall spending on smoking prevention is well below the levels recommended by the CDC.

Nicotine Addiction

Nicotine is the chemical in cigarettes and other forms of tobacco that makes them addictive. About 85% of smokers are addicted to nicotine. Higher levels of nicotine in a cigarette can make it harder to quit smoking. The amount of nicotine in cigarettes has increased compared to two decades ago. Chemicals are also usually added or the cigarette manufacturing process modified to purposefully increase the free nicotine content or the potency of the inhaled smoke and deliver a more powerful "kick". Higher nicotine levels have been found in all cigarette categories, including "light" brands.

Some researchers consider nicotine to be as addictive as heroin. In fact, nicotine has actions similar to heroin and cocaine, and it affects the same area of the brain as these drugs.

Depending on the amount taken in, nicotine can act as either a stimulant or a sedative.

Cigarette smoking produces mental effects very quickly. For example, it can:

- Boost mood and relieve minor depression

- Suppress anger

- Enhance concentration and short-term memory

- Produce a sense of well-being

Most smokers have a special fondness for the first cigarette of the day because of the way brain cells respond to the day's first nicotine rush. Nicotine, particularly in those first few cigarettes, increases the activity of dopamine, a chemical in the brain that elicits pleasurable sensations. This feeling is similar to getting a reward.

Over the course of a day, however, the nerve cells become desensitized to nicotine. Smoking becomes less pleasurable, and smokers may need to increase their intake to get their "reward." A smoker develops tolerance to these effects very quickly and requires increasingly higher levels of nicotine.

Smokeless Tobacco

Smokeless tobacco, also called spit tobacco, includes chewing tobacco (dip and chew), tobacco powder (snuff), as well as flavored tobacco lozenges. These products also contain nicotine.

With smokeless tobacco products, nicotine is absorbed by the digestive system or through mucus membranes. Smokeless tobacco contains at least 28 cancer-causing substances, and is not a safe substitute for smoking cigarettes or cigars. According to the National Institutes of Health, chewing on an average-sized piece of chewing tobacco for 30 minutes can deliver as much nicotine as smoking three cigarettes.

Smokeless tobacco is addictive, and evidence suggests that it increases the risk for oral cancer, gingivitis, and tooth loss. The use of smokeless tobacco increases risk for oral, esophageal, and pancreatic cancers. Using smokeless tobacco also seems to increase the risk for fatal heart attacks and strokes.

Pipes and Cigars

Pipe and cigar smoking are on the rise. Because pipe and cigar smokers often do not inhale, the common misperception is that they don't face as substantial a health risk as cigarette smokers. Yet research finds that smoking pipes or cigars causes harmful health effects similar to those of cigarettes.

Increased risk for mouth, throat, and lung cancers is one concern. People who smoke pipes or cigars are at greater risk for lung damage and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), even if they never smoked cigarettes.

One type of pipe, the water pipe (also known as a "hookah"), is popular among youth and college students, in part because of the mistaken belief that it is less harmful than regular cigarettes. Yet studies have found that smoking a water pipe carries many of the same risks as smoking cigarettes, including lung cancer, other lung disorders, and gum disease.

Electronic cigarettes

E-cigarettes are vaporizer devices that mimic cigarette smoking. They use battery power to operate a heating element that disperses a nicotine-containing solution. Use of e-cigarettes (called vaping) is on the rise, particularly among young people, and the health effects of this practice in non-smokers are still unclear. Vaping was originally marketed as a smoking cessation therapy, as it is likely less harmful than smoking tobacco. However due to the highly addictive properties of nicotine, around a third of first-time users become addicted to nicotine, and non-smokers who vape have a higher likelihood to start smoking.

Although health effects of nicotine vaping are still being studied, they are likely to be similar to those of smokeless tobacco. However vaping devices may also be used with cartridges containing cannabis products. An outbreak of e-cigarettes or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI) occurred in the United States in 2019. The CDC linked EVALI to vitamin E acetate, an additive in illegal cartridges of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive compound in marijuana.

Health Risks

Smoking, even just a few cigarettes a day, has been linked to many serious health risks. Up to one-half of all current tobacco users will die from a tobacco-related disease, many of which are discussed below.

Lung Cancer and Other Lung Diseases

Smoking is the number one cause of lung cancer. Secondhand smoke also increases the risk for lung cancer and other lung conditions caused by smoke. According to the American Lung Association, smoking is directly responsible for about 90% of the deaths due to lung cancer. The good news is that as smoking rates have declined, lung cancer rates have dropped too. From 2013 to 2016, new lung cancer cases decreased by 4%.

Smoking is also responsible for most cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as well as most deaths due to COPD, which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis. And smoking makes it harder to control asthma, by interfering with the response to steroid medicine and worsening lung function.

COPD

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) -- emphysema and chronic bronc...

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Cardiovascular Disease

Smoking, chewing tobacco, and being exposed to secondhand smoke all greatly increase the risk for heart attacks and strokes. The risk for heart problems in people who smoke or who are exposed to smoke may be three times greater than that of people who don't smoke. When people stop smoking, their risk of having a heart attack decreases over time.

Smoking also significantly increases the risk for peripheral artery disease, which damages the blood vessels in the legs and can lead to disability and amputation.

Effects on Male Fertility and Erectile Dysfunction

Smoking can harm a man's sexuality and fertility. Smoking increases the risk for erectile dysfunction (ED), and the cumulative dose of cigarette exposure is associated with ED severity.

Smoking impairs sperm motility, reduces sperm lifespan, and may cause genetic changes that can affect a man's offspring. Men who smoke have less success with fertility treatments. They also have a lower sex drive and less frequent sex.

Effects on Female Infertility, Pregnancy, and Childbirth

Studies have linked cigarette smoking to infertility in women, and to health problems in their babies.

Negative effects of smoking include:

- Greater risk for infertility. Women who smoke one or more packs a day and who started smoking before age 18 are at greatest risk for fertility problems.

- Earlier menopause. Women who smoke tend to start menopause at an earlier age than non-smokers, perhaps because toxins in cigarette smoke damage eggs.

- Pregnancy complications, which increase with the number of cigarettes smoked.

- Greater risk for sexual dysfunction. Smoking is an independent risk factor for female sexual dysfunction.

Pregnancy complications that are more common in smokers include:

- Miscarriage

- Stillbirth

- Premature rupture of membranes

- Premature delivery

- Problems with the placenta

Smoking further increases the risk to the mother and unborn child in high-risk pregnancies.

Effects on the Unborn Child

Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk for:

- Low birth weight

- Premature birth, which in turn increases the risk for many other health problems

- Stillbirth

- Birth defects (women who smoke during pregnancy have lower levels of folate, a B vitamin that is important for preventing birth defects)

- Obesity and diabetes

- Cleft lip (a split lip that has not closed during the fetus' development)

Some women have genes that may make them especially likely to deliver low-birth-weight infants if they smoke, although newborns of all female smokers are at greater risk for low birth weight. The good news is that women who stop smoking before becoming pregnant or during their first trimester of pregnancy reduce their risk of having a low-birth-weight baby compared to that of women who never smoked.

Women who want to become pregnant should make every attempt to stop smoking, and they should use smoking cessation aids before they try to conceive. Government guidelines recommend that doctors ask all of their pregnant women about their tobacco use, and offer counseling to those women who do smoke. After birth, if new mothers cannot quit or restart smoking, they should at least be sure not to smoke in the same room as their infant.

Pregnant women also need to avoid being around people who are smoking. Women who are exposed to secondhand smoke during pregnancy are 23% more likely to have a stillborn baby and 14% more likely to have a baby with a birth defect than women who are not exposed to secondhand smoke.

Effects on Bones and Joints

Smoking has many harmful effects on bones and joints:

- Smoking can slow the process that adds calcium to bones and makes them stronger. Women who smoke are at higher risk for bone density loss and osteoporosis.

- Postmenopausal women who smoke have a significantly greater risk for hip fracture than those who do not smoke.

- Smokers are more likely to develop degenerative disorders and injuries in the spine.

- Smokers have more trouble recovering from surgery.

Smoking and Diabetes

Smoking increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes or glucose intolerance, a condition that precedes type 2 diabetes. Smokers with diabetes also have more difficulty controlling their blood sugar level and have a higher risk for diabetes complications.

Smoking and the Gastrointestinal Tract

Smoking increases acid production in the stomach. It also reduces blood flow and the production of compounds that protect the stomach lining. This combination of effects increases the risk for certain gastrointestinal conditions.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Smoking has mixed effects on IBD, the collective term for ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. Smokers have lower-than-average rates of ulcerative colitis, but higher-than-average rates of Crohn disease. Smokers with Crohn disease who quit smoking have less severe symptoms than those who continue to smoke.

Ulcerative colitis

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of ulcerative colitis.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Crohn disease

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Crohn disease.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

Inflammatory bowel disease

Crohn disease, also called regional enteritis, is a chronic inflammation of the intestines which is usually confined to the terminal portion of the small intestine, the ileum. Ulcerative colitis is a similar inflammation of the colon, or large intestine. These and other IBDs (inflammatory bowel disease) have been linked with an increased risk of colorectal cancer.

Colorectal Cancer

Smoking increases the risk for colorectal cancer and aggressive colon polyps, which are considered precursors to colon cancer.

Colorectal cancer

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of colorectal cancer.

| Read Article Now | Book Mark Article |

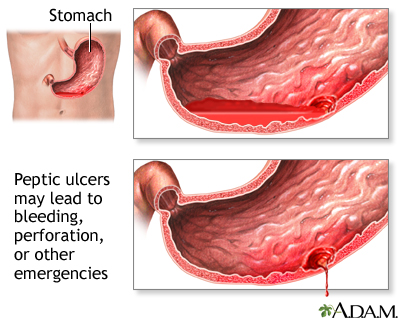

Ulcer emergencies

Peptic ulcers may lead to emergency situations. Severe abdominal pain with or without evidence of bleeding may indicate a perforation of the ulcer through the stomach or duodenum. Vomiting of a substance that resembles coffee grounds, or the presence of black tarry stools, may indicate serious bleeding.

Hepatitis and Cirrhosis

Smoking is linked to increased liver scarring in people with cirrhosis, due to excessive drinking, hepatitis B or C viruses, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Smoking and Other Types of Cancer

Bladder Cancer

Smoking is the single biggest risk factor for bladder cancer, which is diagnosed in about 77,000 Americans each year. The risk for bladder cancer among smokers may be even higher than was once thought. Current smokers are four times as likely to get the disease as non-smokers, and former smokers face double the risk for bladder cancer. Both female and male smokers face similar odds of getting bladder cancer.

Prostate Cancer

Men who smoke at the time of their diagnosis with prostate cancer fare much worse than non-smokers. Smokers are 61% more likely to see their prostate cancer return, and twice as likely to die from their cancer as men who never smoked. Men who quit smoking at least 10 years before their diagnosis are at the same risk as those who never smoked.

Other Cancers

Besides lung, colorectal, bladder, and prostate cancer, several other cancer types are associated with smoking. Smoking clearly increases the risk for oral, pharyngeal, esophageal, laryngeal, stomach, pancreas, kidney, cervical cancers, as well as blood cancers like acute myeloid leukemia, and skin cancers like melanoma.

Smoking and Thyroid Disease

Cyanide, a chemical found in tobacco smoke, interferes with thyroid hormone production. Smoking triples the risk of developing thyroid disease, particularly hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid). Smoking has also been linked to goiter, a swelling of the thyroid that occurs in people who do not get enough iodine.

Brain-thyroid link

Although the thyroid gland releases the hormones which govern growth and metabolism, the brain (the pituitary and the hypothalamus) manages the release and the balance of the amount of hormones circulated.

Smoking and Surgical Recovery

Smokers are at increased risk for heart and circulatory problems and delayed wound healing after surgery. Quitting smoking significantly lowers the risk for these complications. The longer patients are off cigarettes before their surgery, the better they will do after the procedure.

Limited evidence suggests that interventions that begin four to eight weeks before a surgery may have an impact on complications and on long-term smoking cessation, but more research is necessary.

Physicians often recommend to their patients that they seek counseling and medicines to quit smoking after hospital discharge, but compliance with recommendations is low. Experts are studying different methods of post-discharge intervention.

Infections

Smoking interferes with the normal function of the immune system and increases the risk for viral and bacterial infections, including respiratory infections, urinary tract infections, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Smoking and Age-Related Disorders

The following age-related conditions are thought to occur at higher rates in smokers than non-smokers:

- Cataracts. Quitting smoking reduces your chances of needing cataract surgery in the future, although you will still face a greater risk for this surgery than non-smokers.

Cataract

The lens of an eye is normally clear. If the lens becomes cloudy (opacified) it is called a cataract.

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is a leading cause of blindness in older people. Smoking is the second biggest risk factor for AMD, after age. Heavy smoking over a long period of time can significantly increase AMD risk.

-

Alzheimer disease

and dementia. Heavy smoking during middle age increases the risk for Alzheimer disease and dementia by 100% in later life.

Alzheimer disease

An in-depth report on the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer disease.

Read Article Now Book Mark Article - Gum disease and tooth loss. One half or more of the cases of severe gum disease in American adults may be due to cigarette smoking.

- Skin wrinkles. Smokers are nearly five times more likely to develop more and deeper skin wrinkles as they age compared to nonsmokers.

- Baldness and premature gray hair. Certain chemicals in smoke break down in hair cells, which leads to hair damage.

- Hearing loss, particularly high-frequency hearing loss.

- Urinary incontinence. Smoking more than doubles the risk for stress urinary incontinence.

Secondhand Smoke

All burning tobacco products produce secondhand smoke. About 58 million non-smokers are exposed to secondhand smoke each year. Two of five children are regularly exposed to secondhand smoke. Secondhand smoke from parents has been shown to affect infants' lungs as early as the first 2 to 10 weeks of life. This abnormal lung function could persist throughout a child's life.

Exposure to secondhand smoke in the home increases the risk for:

- Asthma and asthma-related emergency room visits in children who have existing asthma

- Weight problems

- Behavioral problems

- Lower respiratory tract infections (such as bronchitis or pneumonia)

Being exposed to secondhand smoke also increases the risk for heart attacks and lung cancer.

Smoking Bans

More and more households in the United States are banning smoking. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 83% of households forbid smoking at any time or place.

Smoking bans are extending to public places, as well. In 2002, Delaware became the first state to institute a smoke-free law. Since then, smoking bans have spread across the country. Currently, 26 states have laws prohibiting smoking in restaurants, bars, and offices. Twelve other states have laws banning smoking in some of these places.

The risk for hospitalization for heart attacks in communities that enforce smoking bans has decreased by 15% overall. Younger people and non-smokers seem to benefit the most from such bans.

Quitting Smoking

It's never too late to quit smoking. According to the American Cancer Society, about one-half of all smokers who keep smoking will die from a smoking-related disease. Quitting has immediate health benefits.

Better Health After Quitting |

|

|

Time after last cigarette |

Physical Response |

|

20 minutes |

Blood pressure and pulse rates return to normal. |

|

12 hours |

Levels of carbon monoxide and oxygen in the blood return to normal. |

|

24 hours |

Chance of a heart attack begins to decrease. |

|

48 hours |

Nerve endings start to regrow. Ability to taste and smell increases. |

|

72 hours |

Bronchial tubes relax and the lungs can fill with more air. |

|

2 weeks to 3 months |

Circulation improves and lung function increases by up to 30%. |

|

1 to 9 months |

Rates of coughing, sinus infection, fatigue, and shortness of breath decrease. Cilia in the airways regrow, improving the ability to clear mucus and clean the lungs, and reducing the chance of infection. Energy level increases. |

|

Long-Term Effects |

After a year, the risk of dying from a heart attack or stroke is reduced by up to 50%. Within 10 years, the risk of dying from lung cancer is about one half that of a smoker. Within 15 years, the risk for coronary heart disease is the same as that of a non-smoker. |

About 52% of smokers who want to quit make a serious attempt to do so each year, but fewer than 7% actually succeed. Available smoking cessation products and therapies are greatly underused. If more smokers asked for or were offered such help, quit rates could double or triple.

Some people have genes that make quitting harder or easier. Researchers have identified more than 200 genes that may contribute to the rate of success in quitting smoking. The discovery of these genes could theoretically lead to new smoking cessation therapies that target a person's specific genetic makeup.

Quitting smoking

The many methods of quitting smoking include counseling and support groups, nicotine replacement therapy, prescription medications, and incremental reduction.

Methods of quitting smoking include counseling and support groups, nicotine patches, gums, lozenges, and sprays, e-cigarettes, smoking cessation pills, exercise, and slowly cutting back on the number of cigarettes smoked (incremental reduction). A combination approach may be most effective. Interventions may be administered in the workplace, or other organizations such as your local hospital or public health office.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)

Nicotine replacement therapy involves the use of products that provide low doses of nicotine, without the toxic byproducts of tobacco burning found in smoke. The goal of therapy is to relieve cravings for nicotine and ease the symptoms of withdrawal.

In general, NRT benefits moderate-to-heavy smokers the most. However, it also appears somewhat helpful for light smokers (people who smoke fewer than 15 cigarettes a day).

All forms of NRT can be effective in promoting smoking cessation. NRT increases the quit rate by 50% to 60% for at least 6 months or longer. Most of the research is focused on adults, but adolescents may also benefit from NRT.

Combining NRTs may be more effective than using one alone. For example, a combination of the nicotine patch and nicotine gum, nasal spray, or lozenge helps smokers go smoke-free for a longer period of time before relapsing. Adding bupropion to NRT also increases the chance for success.

Nicotine Patches

Nicotine patches deliver nicotine through the skin. This is called transdermal nicotine delivery. It is effective at reducing withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine patches are available over the counter.

Patches work in different ways:

- Step-Down Approach. Patches that use this method include Habitrol and NicoDerm CQ. The patches come in three strengths (21, 14, and 7 mg). You use the strongest dose first if you smoke more than 10 cigarettes daily and reduce the dose gradually over a period of 8 to 10 weeks. A 21 mg patch is about equal to 15 cigarettes. A heavy smoker may need to wear two patches at first.

How patches are applied and used:

- A single patch is worn each day and replaced after 24 hours.

- To avoid skin irritation it is applied to different hairless areas above the waist and below the neck each day.

- People can wear the patches for 24 hours, but some have reported odd dreams and have disliked the sensation of wearing the patch during the night. However, people who wear the patch all the time have fewer withdrawal symptoms and slightly better quit rates than those who take it off at night.

Store and discard patches safely, particularly in homes with young children. Children have been poisoned and have gotten sick from wearing, chewing, or sucking on nicotine patches. Children should not come in contact with the patches, even while the smoker is wearing them. If a child puts on a patch, remove it and wash the affected skin right away. A child who has eaten nicotine or worn a patch for a long period of time may need urgent medical care.

Nicotine Gum

Nicotine gum (for example, Nicorette) is available over the counter and has helped many people quit. Some people prefer gum to the patch because they can control the nicotine dosage, and chewing satisfies the oral urge associated with smoking.

Tips for using the gum:

- If you are just starting to quit, chew 1 to 2 pieces every hour or two. Do not chew more than 24 pieces a day.

- Gradually taper off. The goal is to stop using the gum by 3 months (although about 3% of people continue to use it long after they have quit smoking).

- Chew the gum slowly until it develops a peppery taste. Then tuck it between the gum and cheek, so that the nicotine can be absorbed.

- Coffee, tea, soft drinks, and acidic beverages may interfere with nicotine absorption, so wait at least 15 minutes after having one of these drinks before chewing a piece of gum.

Some people prefer other methods or cannot use the gum for the following reasons:

- They find the taste of the gum unpleasant.

- Side effects of the gum may include upset stomach, mouth sores, hiccups, and throat irritation.

- They are embarrassed to chew gum.

- They wear dentures.

Long-term dependence may be a problem with nicotine gum. Experts do not recommend that people chew nicotine gum for more than 6 months.

The Nicotine Inhaler

The nicotine inhaler resembles a plastic cigarette holder. It requires a prescription in the United States. The inhaler comes with several nicotine cartridges, which are inserted into the inhaler and "puffed" for about 20 minutes, up to 16 times a day. The dose is gradually decreased.

Several studies have reported that the inhaler can double or triple quit rates compared with a placebo after 6 months. The inhaler has some advantages over other nicotine replacement products:

- It provides varying doses of nicotine on demand (as opposed to continuous doses with the patch or gum) and is relatively fast-acting. Blood nicotine levels peak about 20 minutes after using the inhaler, comparable to the gum and faster than the patch.

- It satisfies oral urges.

- Most of the nicotine vapor is delivered into the mouth, not into the lung airways (although some people experience mouth or throat irritation and a cough).

Using a combination of the inhaler and the patch may be more effective than either method alone.

The Nicotine Nasal Spray

The nasal spray satisfies immediate cravings by providing fast doses of nicotine. (Nicotine levels peak within 5 to 10 minutes after administering the spray.) It may be useful together with slower-acting nicotine replacement therapies.

The spray can irritate the nose, eyes, and throat, so it may not be suitable for people with allergies or sinus infections. Most people, however, can tolerate the side effects, which usually go away within the first few days.

Nicotine Lozenge

A nicotine lozenge (for example, Nicorette or Commit) is available over the counter. It is made from pressed tobacco and comes in two strengths for heavier or lighter smokers. Suck on one piece every 1 to 2 hours, then gradually taper off your use. Do not eat or drink 15 minutes before using a lozenge, and do not take more than 20 lozenges a day. Side effects include heartburn, hiccups, nausea, headaches, and cough. The Commit lozenge also contains phenylalanine, a chemical that certain people may need to avoid.

Electronic cigarettes (E-Cigarettes)

E-cigarettes are battery-operated devices of various shapes that deliver nicotine and other substances in the form of a vapor. Many e-cigarettes are marketed as quit-smoking aids because they are designed to give the feeling of smoking without actually lighting up. The chemicals and substances in e-cigarettes vary, and labeling is often inconsistent.

Several small studies have evaluated whether e-cigarettes can help some people quit smoking. The US Preventive Task Force reports that any evidence that supports the use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation is quite limited and does not show benefit among smokers intending to quit. None of the specific products have been approved as cessation interventions by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

E-cigarettes and vaping are increasingly popular among children and adolescents who do not smoke. Researchers worry that by creating nicotine addiction in people who are not current smokers, e-cigarettes may serve as gateway products leading to smoked tobacco use.

The FDA has not approved these devices for smoking cessation. However, the FDA has announced that it has finalized a rule that allows it to regulate e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems similar to the way that it regulates tobacco products. This will require that e-cigarette manufacturers provide the government with a list of ingredients contained in their products.

Facts about Nicotine Replacement Therapy:

- Not cheating on the very first day of nicotine-replacement use increases the chance of quitting permanently by ten times.

- The more cigarettes people smoke, the higher the dose of nicotine replacement they may need at first.

- Adding a counseling program can boost the effectiveness of any nicotine replacement program.

- Nicotine replacement helps prevent weight gain while you are using it, but you are still at higher risk of gaining weight when you stop using all nicotine.

Side Effects

Besides nicotine dependence, side effects of any nicotine replacement product may include headaches, nausea, and other gastrointestinal problems. People often experience sleeplessness in the first few days, particularly with the patch, but the insomnia usually passes. People using very high doses of nicotine are more likely to have symptoms. Reducing the dose can prevent these symptoms.

Special Concerns for Specific Individuals

There has been some concern that the patch might be harmful for people with heart or circulatory disease, but studies are finding that it actually poses little or no danger for these individuals. In fact, the patch may help reduce angina attacks brought on by exercise. However, unhealthy cholesterol levels (lower HDL levels) caused by smoking will not improve with the nicotine patch. HDL levels will only improve when all nicotine is stopped.

Nicotine replacement may not be completely safe in pregnant women, although it has been used in this group without problems. Its ability to help pregnant women quit smoking is not well proven.

Nicotine Products and Children

Keep all nicotine products away from children. Nicotine is a poison. Call a physician or poison control center immediately if a child has been exposed to a nicotine replacement product, even for a short period of time. Also call the doctor if a child has been exposed to a nicotine product and has any symptoms, including upset stomach, irritability, headache, rash, or fatigue.

Warnings Against Long-Term Use

No one should use nicotine replacement therapies as a long-term substitute for smoking. Any nicotine replacement therapy should only be used temporarily.

Antidepressants for Smoking Cessation

Bupropion (Zyban or Wellbutrin)

Bupropion is a type of antidepressant that is also FDA-approved for smoking cessation. Bupropion differs from many other antidepressants in that it increases the effects of dopamine, the brain chemical that appears to play a strong role in nicotine addiction. Using bupropion along with nicotine replacement therapy may help control cigarette cravings.

People usually start taking bupropion a week or two before quitting, and continue taking it for 7 to 12 weeks. The usual maintenance dose is a 150 mg tablet taken twice a day. No single dose should be higher than 150 mg.

Side effects of bupropion include:

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Headaches

- Insomnia

- Dry mouth

- Irritation

In very rare cases, seizures have occurred, although usually in people who exceeded the recommended dose or who were already at risk for seizures.

Warning about Bupropion

In 2009, the FDA required the makers of bupropion to add a boxed warning (the strongest possible warning) regarding serious mental health side effects that may occur while using the medicines. These potentially serious side effects include changes in behavior such as hostility, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal thoughts or actions. People taking this medicine, as well as their family members, should be aware of these potential dangers and report any symptoms to their doctor immediately. People are also advised to stop taking the medicine immediately if any of these symptoms occur.

Nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl)

The tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline may reduce the actions of nicotine and help smokers quit, although it was not approved by the FDA for this purpose. Quit rates with this medicine are as high as 30%. Long-term abstinence rates are more than twice those of placebo (sugar pill). It is best to start taking this medicine 10 to 28 days before your intended quit date.

Side effects of nortriptyline include:

- Drowsiness

- Dry mouth

- Changes in taste

- Constipation

In rare cases, tricyclic antidepressants like nortriptyline can have more serious side effects. An overdose can be deadly. Tricyclics may also pose a danger for patients with certain types of heart disease.

Varenicline

Unlike bupropion, varenicline (Chantix) targets nicotine receptors in the brain, which helps reduce cravings. Varenicline can also help people wean themselves off smokeless tobacco.

Cigarette smokers ages 18 and older can use varenicline. This drug may be used along with nicotine replacement therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Warnings about varenicline (Chantix)

Varenicline carries a boxed warning regarding serious mental side effects that may occur while using the medicine, or immediately after stopping it. These uncommon but potentially serious side effects include changes in behavior such as agitation, depressed mood, suicidal thoughts or actions. Recently, the FDA updated the varenicline label, after the drug was associated with an increased risk for heart problems, such as a heart attack and abnormal heart rhythms. People who take this medicine should be aware of these potential dangers and report any symptoms to their doctor immediately.

Behavioral Methods and Counseling

Everyone who quits should aim to quit completely. Quitting completely is essential to regaining good health and reversing the harmful effects caused by smoking. Just reducing smoking, even by one half, does not eliminate the risk for cancer and other health problems. Although smokers who cut back take in less smoke and nicotine, their bodies are still unable to heal completely from the ongoing intake of toxins. Changing to low-tar cigarettes is also not a solution. In fact, people who smoke these cigarettes tend to inhale more deeply, which may increase their health risks.

Most people who return to smoking "cheat" in the first few weeks. To help you, make a quit-smoking plan and stick to it.

Create a List

Write down 10 reasons to quit. In addition to health reasons, the list might include:

- Having better smelling hair, clothes, and breath

- Having fewer skin wrinkles

- Enjoying the taste of food

- Saving money

Read the list often during the quitting process to help you stay motivated.

Decide on a Specific Quit Date

Some people find it helpful to choose a date when they anticipate having little or no stress for at least 3 days. Once you have chosen a date:

- Write out a quit contract, put the date on paper, and get a friend to sign it.

- Throw out all smoking paraphernalia the night before the quit date.

- Make plans to stay busy on the quit day, especially at night, when your urge to smoke will be high.

If quitting cold turkey isn't for you, gradually stopping is an equally effective approach. Reducing the number of cigarettes you smoke before your quit day might work just as well as stopping all at once.

Make an Oath

Take an extreme oath. For example, "If I smoke one more cigarette my dog will die." Although this seems absurd, some people who have failed with all other methods have reported that they quit completely and successfully after taking such an oath.

Let the Body and Mind Heal During Withdrawal

- Retreat from the world when cravings become overwhelming. Take a nap, warm bath or shower, meditate, or read a novel.

- Help your body get rid of nicotine. Drink plenty of water. Eat fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fiber-rich foods. Munch on carrots, apples, and celery.

- When cravings occur, take a few deep, rhythmic breaths.

- Use meditation or relaxation and deep breathing exercises, especially when you feel the urge to smoke.

Get Family and Friends Involved

- Tell your friends and family that you have already quit, so you will be embarrassed if they catch you smoking.

- Fine yourself. Pay a family member or friend if they catch you smoking. The amount should be large enough ($5 to $20) to be a deterrent, but not so large as to be ridiculous. Save up for something special, or donate the money to charity.

- If your partner or friend smokes, try persuading them to quit. At the very least, ask the person not to smoke around you.

Exercise

Studies continue to show that smokers who exercise can greatly increase their ability to quit smoking and reduce their risk for weight gain in the short term. When you have cravings:

- Dance

- Run

- Walk

- Jump up and down

- Stretch

- Do push-ups

- Do yoga

Older people and anyone with health problems should consult their health care provider before starting an exercise program.

More research is necessary to determine the level of exercise and support needed to quit for the short and long term.

Maintain a Healthy Diet

- Eat plenty of fresh, crunchy fruits and vegetables. This is also a useful way to satisfy oral cravings without adding many calories.

- Drink plenty of water and healthy beverages.

- Drink coffee or tea in moderation. These drinks may help prevent weight gain, and may also boost alertness and mood. Avoid caffeine in the evening, however, since sleep disturbances can be a problem during withdrawal.

Change Daily Habits

- Change your daily schedule, particularly eating times, as much as possible. Eat at different times of the day or eat many small meals instead of three large ones. Sit in a different chair or even a different room while you eat.

- If you smoke after eating, find other ways to end a meal. Play music, eat a piece of fruit, get up and make a phone call, or take a walk (a good distraction that burns calories as well). If you normally have a cigarette with coffee, drink tea instead or use a different cup.

- Substitute oral habits by eating celery, chewing sugarless gum, or sucking on a cinnamon stick.

- Go to public places and restaurants where smoking is prohibited or restricted.

- Set short-term quitting goals and reward yourself when you meet them.

- Every day put the money you'd normally spend on cigarettes in a jar and buy something you want at the end of a set period of time.

- Find activities that focus your hands and mind but are not taxing or fattening, such as playing computer games or solitaire, knitting, sewing, or doing crossword puzzles.

About 4% of smokers who try to quit without any outside help succeed. Nevertheless, most people try to quit alone. The primary obstacle to quitting on your own is eliminating the habits associated with smoking. Excellent books, CDs, and manuals are available to help you quit on your own.

Smokers who use outside help or treatments fare better luck, with success rates of 25% to 35%. Those who are counseled in addition to using NRT and another drug have the best chance at quitting. Talking with a counselor can also help. Telephone counseling has been effective for quitting smokeless tobacco.

Studies have shown that interventions that combine medicine with behavioral counseling (at least 4 to 8 sessions) are more effective than brief advice or usual care.

Types of Behavioral Approaches

Problem Solving or Coping Strategies

Smokers are more likely to quit smoking when they learn thinking (cognitive) and behavioral techniques, stress management techniques, and ways to handle the symptoms of withdrawal and the urge to relapse. Smokers should look for programs that offer the following:

- Session lengths of 20 to 30 minutes

- Four to seven sessions

- A 2-week program

- An additional 2 weeks or more of follow-up contact

The Staged Approach

The staged approach customizes quitting interventions for each person, rather than using one general method. This approach takes the smoker through six stages of behavioral interventions:

- Pre-contemplation

- Contemplation

- Preparation

- Action

- Maintenance

- Termination

People who follow this approach do not always proceed from one stage to another in a step-by-step fashion. Instead, they may cycle or spiral back and forth. Some people may move from stage 1 to 2 to 3, and then back to 2 again. You can stay in maintenance mode for years and then fall back to stage 2. Remember that this is normal, if you tried quitting in the past and did not stick with it, do not consider yourself a failure. Just try again.

Stage 1: Pre-Contemplation

People at this stage have no plans or desire to stop smoking. They are not even considering quitting. They may be unaware of the benefits of quitting. Or, they may have failed while trying to quit in the past and given up. There is no point in talking about how to start a smoking cessation program at this stage. Instead, it is important to think about how quitting will help you feel better, have more confidence, or live longer. You must identify the benefits before you will consider quitting. If you are at this stage, it can help to ask several friends or family members why they quit smoking.

Stage 2: Contemplation

A person at this stage is thinking, "I think I should probably quit, but I need help getting started." People at this stage know that quitting is good for them, but it seems like a daunting task or they do not think they can pull it off. Some may have tried and failed in the past. If you are at this stage, write down (brainstorm) all of your potential roadblocks, the things that you believe make quitting difficult, and learn strategies to overcome or sidestep those hurdles. People at this stage might benefit from making a pledge, contract, or other commitment.

Stage 3: Preparation

Smokers at this stage are ready to quit. The goal now is to create a specific action plan. You need to know which smoking cessation methods work and what support exists to help you quit. If you are at this stage, consider some backup plans, such as what to do when the urge to smoke hits you.

Stage 4: Action

People at this stage have just quit. This stage is when the most behavioral change occurs. It requires significant commitment and energy. If you are at this stage, keep talking to friends and family for inspiration. Review your backup plans. Reward yourself for small achievements. Having a fellow smoker quit with you can be a huge support as you both get through this stage.

Stage 5: Maintenance

People at this stage have been smoke-free for at least 6 months. The goal now is to prevent a relapse. If you are at this stage, continue to be wary of roadblocks and keep reminding yourself of the benefits you have gained. Consider what you have enjoyed most about being smoke-free.

Electronic, online, and computer cessation programs have a small but important impact on cessation. The relatively low cost of electronic interventions make them a good option.

Economic Incentives

Two types of incentive-based programs have been evaluated. The first type of program involves reward money being provided at the end of a period of smoking cessation. This type of program requires funding, most often by employers. These programs have demonstrated modest success.

The second involves placing a deposit at the time of sign up, using the person's own money. It is harder for this type of program to recruit participants, but the quit rates are higher than with reward programs described just above.

Alternative Methods for Quitting

Hypnosis

Although rigorous studies on hypnosis are lacking, some people report successfully quitting after hypnosis sessions. Hypnosis requires you to trust the therapist and be able to feel completely at ease in the vulnerable and passive state necessary for hypnotic suggestion.

During a typical session, the hypnotherapist will use various techniques (such as imagery and silent counting) to put you into a relaxed state.

When you are very relaxed, but not asleep, the hypnotherapist will quietly suggest motivations for not smoking and reinforce a positive self-image. This may help some people avoid the depression that can accompany withdrawal.

Acupuncture and Acupressure

More research is needed to determine if acupuncture or acupressure helps people quit smoking. The acupuncture technique for quitting smoking usually uses very tiny curved staples inserted into different points around the edge of the ear or other parts of the body, which should be pressed in the case of a craving.

A related technique called acupressure involves pressing certain points on your body when a craving hits. Some studies have reported good short-time quit rates with acupuncture, but few well-designed and rigorous studies have been conducted.

Public Health Efforts and Social Pressure (Denormalization)

Denormalization is the idea that smoking is no longer normal or socially acceptable. Examples include:

- Creating laws and local regulations that make smoking inaccessible in public places

- Raising prices on cigarettes

- Putting stricter limitations on cigarette advertising

Increasing taxes on cigarettes may be one of the most important methods for reducing smoking in the general population, particularly in younger people.

Evidence suggests that banning smoking in work and public places may lead to a higher quit rate than in places where smoking is permitted. In addition, banning smoking in public spaces reduces exposure to secondhand smoke for both non-smokers and smokers.

Symptoms of Withdrawal

After you quit smoking, you are likely to have some withdrawal symptoms. These symptoms generally peak in intensity 3 to 5 days after you quit, and usually disappear after 2 weeks, although some may persist for several months.

The symptoms of withdrawal are both physical and mental.

Physical Symptoms:

- Tingling in the hands and feet

- Sweating

- Intestinal disorders (such as cramps and nausea)

- Headaches

- Sore throat, coughing, and symptoms of a cold

Treat withdrawal symptoms just like you would treat physical symptoms from an illness or disease.

Mental and Emotional Symptoms

Cravings can build up during withdrawal, sometimes to a nearly intolerable point. Nearly every moderate-to-heavy smoker who quits experiences more than one of the following emotional and mental responses to withdrawal:

- Temper tantrums, intense needs, feelings of dependency

- Insomnia

- Mental confusion, vagueness, or difficulty concentrating

- Irritability, restlessness, impatience, or anger

- Anxiety

- Depression

The first signs of nicotine withdrawal can appear within 30 minutes of a smoker's last cigarette. Within 3 hours, the person may experience anxiety, sadness, and difficulty concentrating.

Long-Term Depression

Depression is common in smokers during withdrawal and over the long term. In the short term, it can mimic the feelings of grief that a person might experience after the loss of a loved one.

Cigarette smoking is strongly linked to depression. People who are already prone to depression have a 25% chance of becoming depressed when they quit smoking, and this increased risk persists for at least 6 months. What's more, depressed smokers are very unlikely to quit successfully. Only about 6% remain smoke-free after a year.

However, for those who are able to quit, there is evidence from studies that mood, depression, anxiety, and stress are improved after successfully quitting.

If you experience depression while quitting, try a combination of emotionally supportive therapy, nicotine replacement, and antidepressants such as bupropion (Zyban). If severe depression lasts beyond the withdrawal period, seek professional help as soon as possible.

Weight Gain

Quitting smoking does increase the risk for weight gain in most quitters but the amount of weight gain (or loss) varies widely. After quitting smoking, your body's metabolism slows down, so you burn food more slowly. On top of that, quitting restores normal appetite, so you may feel hungry more often. If you do gain weight, most of the weight gain occurs in the first three months.

Smokers who quit gain an average of 11 pounds by the end of their first year, and an extra 6 to 7 pounds in the next 4 years. These are averages however, and studies have shown that about 16% of smokers lose weight after quitting. Another 13% of quitters may gain up to 22 pounds after cessation.

The fear of weight gain shouldn't stop you from quitting smoking. The health benefits of cessation far outweigh the risks for weight gain. For best results, you should use weight-control measures after quitting.

How to Keep the Weight Off After Smoking

Exercise is very helpful for controlling weight. To burn the same amount of calories as you did while smoking, take an extra 15-minute daily walk and eliminate 100 calories a day. Just a moderate increase in physical activity can keep weight gain to a minimum. Nicotine replacement therapy can also help prevent weight gain.

Combining behavioral therapy for smoking-related weight gain with the antidepressant bupropion can help people who are worried about gaining weight after quitting stop smoking for longer.

[See the Quitting Smoking section in this report.]

Barriers to Quitting

Biological, psychological, behavioral, and cultural factors all play a role in nicotine addiction, making smoking one of the hardest addictions to beat. About one-half of people who quit return to smoking. Even after years of not smoking, some ex-smokers still have occasional cravings for cigarettes.

In addition to depression, there are three other major reasons why people have a hard time quitting:

- Mental performance. Nicotine improves concentration and thinking. Quitting smoking temporarily impairs mental performance.

- Stress. Although smoking may not reduce stress, stopping increases it.

- Weight gain. Quitting smoking can cause weight gain, which is a major factor in smoking relapse. [See Weight Gain section in this report.]

The first 2 weeks of smoking cessation are critical to the overall success of the program. Smokers should seek all the help they can get during this period. Although withdrawal symptoms can be intense, treatments are available to reduce them.

Attempts to quit are never a waste of time, because you reduce the amount you smoke during these periods. People who keep trying have a 50/50 chance of finally quitting.

Risk Factors for Failure

Researchers have been trying to discover risk factors or sets of behaviors that can help predict why some people are not able to quit smoking. Factors include:

- Being female

- Being a heavy smoker

- Inhaling deeply

- Being a long-term smoker

- Having severe withdrawal symptoms

However, only one factor consistently leads to failure in quitting. Cheating during the first 2 weeks of withdrawal nearly guarantees that a person will smoke again in 6 months.

Women and Smoking

Studies show that women have a harder time trying to quit smoking and have less success with abstinence programs than men. There are many possible reasons for this gender inequality:

- Nicotine has different effects on mood in women than in men. Women who quit may have greater anxiety and stress than men who quit.

- Women may fear weight gain after quitting more than men.

- During certain phases in the menstrual cycle, women may not respond as well to smoking cessation drugs.

- Men may be less supportive than women in helping their partners quit.

- Women who are trying to quit may miss the feeling of control associated with smoking more than men do.

In the past 50 years, women's risk of dying from smoking-related diseases has increased, and is now nearly equal to that of men.

On the positive side, evidence suggests that when women quit, their lung function improves more rapidly than in men who quit.

Lifestyle Changes

Smokers and former smokers should immediately begin to implement a healthier lifestyle and change any other behaviors that might be damaging their health.

Healthy Diet

Maintain a healthy diet by eating:

- Whole grains

- Fruits and vegetables (particularly dark-colored ones)

- Fish at least twice a week (this may help limit the damaging effects of tobacco on the body)

- Monounsaturated fats (found in olive oil) or fats from oily fish, instead of saturated fats

Exercise

Regular exercise reduces a smoker's risk for heart disease (although still not to the level of a non-smoker). Exercise does not lower a smoker's risk for lung cancer or emphysema, however.

Regular Check-Ups

If you smoke, you should be screened for any smoking-related disorders:

- Have your cholesterol and blood pressure checked regularly.

- Women should have regular Pap smears to detect cervical cancer (how often you need a Pap smear depends on your age and medical history) and appropriate testing to screen for breast cancer.

- All adults age 50 years or more should be screened for colon cancer.

The National Lung Cancer Screening Trial found that having an annual low-dose computed tomography (CT) scan can reduce lung cancer deaths in heavier smokers by 20%.

The American Lung Association and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network now recommend low-dose CT screening for the following:

- Annual screening should be offered to current smokers and former smokers who have quit within the past 15 years who are between the ages of 55 to 74 years, have smoked at least 30 packs per year, and have no history of lung cancer.

- Chest x-rays should not be offered as a screening tool.

- Screening should not be viewed as an alternative to smoking cessation.

Screening CT scans produce many false-positive results. This means that many people have suspicious findings on a CT scan that do not turn out to be cancer after a lung biopsy is done. People not meeting the above criteria are unlikely to benefit from lung cancer screening at this time.

Resources

- CDC's Smoking & Tobacco Use resources -- www.cdc.gov/tobacco

- American Cancer Society -- www.cancer.org

- American Lung Association -- www.lung.org

References

Baker TB, Piper ME, Stein JH, et al. Effects of nicotine patch vs varenicline vs combination nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation at 26 weeks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):371-379. PMID: 26813210 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26813210/.

Benowitz NL, Brunetta PG. Smoking hazards and cessation. In: Broaddus VC, Mason RJ, Ernst JD, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 46.

Cahill K, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R. Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD004307. PMID: 25983287 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25983287/.

Cahill K, Lancaster T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD003440. PMID: 24570145 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24570145/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion HealthyPeople.gov website. Tobacco - 2020 Leading Health Indicators Topics. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Tobacco. Updated: May 11, 2020. Accessed: June 6, 2020.

Chamberlain C, O'Mara-Eves A, Porter J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD001055. PMID: 28196405 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28196405/.

Ebbert JO, Hughes JR, West RJ, et al. Effect of varenicline on smoking cessation through smoking reduction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(7):687-694. PMID: 25688780 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25688780/.

Engelmann JM, Karam-Hage M, Rabius VA, Robinson JD, Cinciripini PM. Nicotine dependence: current treatments and future directions. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 24.

George TP. Nicotine and tobacco. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 29.

Halpern SD, French B, Small DS, et al. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2108-2117. PMID: 25970009 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25970009/.

Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD000146. PMID: 29852054 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29852054/.

Homa DM, Neff LJ, King BA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: disparities in nonsmokers' exposure to secondhand smoke--United States, 1999-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(4):103-108. PMID: 25654612 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25654612/.

Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53-59. PMID: 29346338 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29346338/.

Lindson-Hawley N, Hartmann-Boyce J, Fanshawe TR, Begh R, Farley A, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD005231. PMID: 27734465 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27734465/.

Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330-338. PMID: 24378917 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24378917/.

Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Thompson JH, Senger CA, Fortmann SP, Whitlock EP. Behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant women: a review of reviews for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):608-621. PMID: 26389650 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26389650/.

Patnode CD, O'Connor E, Whitlock EP, Perdue LA, Soh C, Hollis J. Primary care-relevant interventions for tobacco use prevention and cessation in children and adolescents: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):253-260. PMID: 23229625 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23229625/.

Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students -- United States, 2011-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361-367. PMID: 27077789 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27077789/.

Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622-634. PMID: 26389730 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26389730/.

Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788-797. PMID: 28654986 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28654986/.

Tappin D, Bauld L, Purves D, et al. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;350:h134. PMID: 25627664 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25627664/.

Thomsen T, Villebro N, Møller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD002294. PMID: 24671929 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24671929/.

Ussher MH, Taylor AH, Faulkner GE. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD002295. PMID: 25170798 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25170798/.

White AR, Rampes H, Liu JP, Stead LF, Campbell J. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000009. PMID: 24459016 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24459016/.

Review Date: 6/7/2020

Reviewed By: David C. Dugdale, III, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of General Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.