Benign prostatic hyperplasia - InDepth

BPH - InDepth; Prostate enlargement - InDepth; Enlarged prostate - InDepthAn in-depth report about the causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

- Highlights

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a condition in which the prostate gland becomes enlarged. The size of the gland does not necessarily predict symptom severity. Some men with minimally enlarged prostate glands experience many symptoms while other men with much larger glands have few symptoms. BPH is very common among older men, affecting about 50% of men over age 60 and 85% of men over age 80.

BPH Symptoms

The symptoms associated with BPH are collectively called lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). These are generally classified as either voiding (obstructive) symptoms or storage (irritative) symptoms.

Common symptoms of BPH include:

- An urgent need to urinate and difficulty postponing urination

- A hesitation before urine flow starts despite the urgency to urinate

- Straining when urinating

- Weak or intermittent urinary stream

- A sense that the bladder has not emptied completely

- Dribbling at the end of urination or leakage afterward

- Frequent need to awaken from sleep to urinate

Urinary retention (inability to void) is a serious symptom of severe BPH that requires immediate medical attention.

Treatment

BPH is not a cancerous or precancerous condition. It rarely causes serious complications, and men often have a choice whether to treat it immediately or delay treatment. Treatment options include medications and surgery. Alpha-blockers and 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) are the main types of drugs used for BPH treatment.

5-ARIs and Prostate Cancer

A controversial matter is whether 5-ARIs help protect against prostate cancer. Studies have suggested that 5-ARIs lower a man's overall risk for developing prostate cancer. The FDA has in the past advised that these drugs may actually increase the risk of developing high-grade aggressive types of prostate cancer. More recent evidence does not indicate an increased risk for cancer with these medicines. They should not be used for prostate cancer prevention.

- Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also called enlarged prostate, is noncancerous cell growth of the prostate gland. It is the most common noncancerous form of cell growth in men. BPH is not a precancerous condition and does not lead to prostate cancer. However, it is possible to have BPH and also develop prostate cancer.

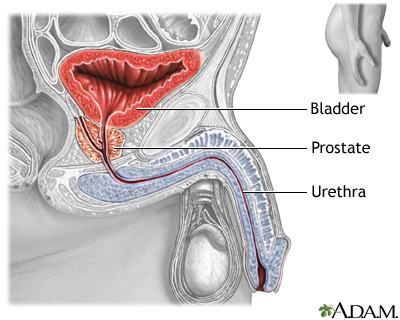

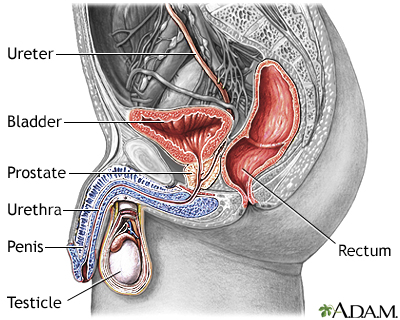

The prostate gland is an organ that surrounds the prostatic urethra in men. It secretes fluid that mixes with sperm to make semen. The urethra carries urine from the bladder and sperm from the testes to the penis.

Hyperplasia is a medical term that refers to an abnormal increase in the number of cells. As prostatic cell growth progresses, it can lead to enlargement of the prostate gland. The enlarged prostate can squeeze the urinary tube (urethra), causing urinary symptoms. These urinary difficulties are part of a group of symptoms called collectively lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

Not all men with BPH have LUTS, and not all men with LUTS have BPH. Lower urinary tract symptoms can also be caused by many other conditions including overactive bladder, urinary tract infections, prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate), and nerve damage that weakens the bladder.

About a third of men with BPH have LUTS that interfere with their quality of life. The size of the prostate gland does not necessarily relate to the severity of a patient's symptoms.

The Prostate Gland

Description of the Prostate Gland

The prostate is a walnut-shaped gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It wraps around the urethra (the tube that carries urine through the penis).

Functions of the Prostate Gland

The prostate gland provides the following functions:

- The glandular cells produce a milky fluid. During ejaculation, the smooth muscles cells contract to squeeze this fluid into the urethra. Here, it mixes with sperm and other fluids to make semen.

- The prostate gland also contains an enzyme called 5 alpha-reductase that converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), another male hormone with a major impact on the prostate.

Changes During the Lifespan

The prostate gland undergoes many changes during the course of a man's life. At birth, the prostate is about the size of a pea. It grows only slightly until puberty, when it begins to enlarge rapidly. It reaches normal adult size and shape, about that of a walnut, when a man is in his early 20s.

The gland generally remains stable until about the mid-40s, when, in most men, the prostate begins to grow again through a process of cell multiplication (hyperplasia). BPH is common in older men. The likelihood of developing an enlarged prostate increases with age.

The Process of Urination

The process of urination is complicated:

- It begins when waste fluids flow out of the kidneys into two long tubes called ureters.

- The ureters empty into the bladder, which rests on top of the pelvic floor, a muscular structure at the base of the pelvis, between the pubic bone and the base of the spine.

- The brain regulates muscles in the urinary tract through a pathway of nerves. As the bladder fills to its capacity of 8 to16 oz (240 to 480 mL) of fluid, the nerves send signals from the bladder to the brain that indicate how full the bladder is.

- As the bladder fills, the bladder wall muscles relax, and the outlet muscles contract to prevent urination.

- At the time of urination, the spinal cord initiates the voiding reflex. The detrusor muscle (which surrounds the bladder) contracts, while the internal sphincter (a strong muscle encircling the neck of the bladder) relaxes. These reactions are involuntary.

- When the internal urethral sphincter is open, urine flows out of the bladder into the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder out through the penis). At the same time, the external urethral sphincter also relaxes. This action is under voluntary (conscious) control from the brain.

- Causes

Doctors are not exactly sure what causes benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The changes that occur with male sex hormones as part of the aging process appear to play a role in prostate gland enlargement.

Male Hormones

Androgens (male hormones) affect prostate growth. The most important androgen is testosterone, which is produced in the testes throughout a man's lifetime, and which is the main androgen present in blood. The prostate converts testosterone to a more powerful androgen, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), by the action of the enzyme 5-alpha reductase.

DHT stimulates cell growth in the tissue that lines the prostate gland (the glandular epithelium) and is the major cause of the rapid prostate enlargement that occurs between puberty and young adulthood. DHT is a prime suspect in prostate enlargement in later adulthood.

Female Hormones

The female hormone estrogen may also play a role in BPH. Some estrogen is always present in men. As men age, testosterone levels drop, and the proportion of estrogen increases, possibly triggering prostate growth. Additionally, testosterone is converted into estrogen in fat tissue by an enzyme called aromatase. This may explain the link between a higher BMI (obesity) and the risk for BPH.

- Risk Factors

Age

Age is the major risk factor for BPH. About half of men develop BPH by age 60, and up to 90% of men in their 70s and 80s have BPH symptoms. It is uncommon for BPH to cause symptoms before age 40.

Family History

A family history of BPH appears to increase a man's chance of developing the condition.

Other Risk Factors

Some evidence indicates that the same risk factors associated with heart disease and type 2 diabetes may increase the risk for development or progression of BPH. These risk factors include obesity, physical inactivity, high blood pressure, and low levels of HDL (good) cholesterol.

- Symptoms

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are categorized either as voiding (formerly called obstructive) or storage (formerly called irritative) symptoms. BPH is often, but not always, the cause of LUTS, largely the voiding symptoms. Other medical conditions, such as bladder problems, can also cause these symptoms.

Some men with BPH may have few or no symptoms. The size of the prostate does not determine symptom severity. An enlarged prostate may be accompanied by few symptoms, while severe LUTS may be present with a normal or even small prostate.

Voiding (Obstructive) Symptoms

Voiding symptoms can be caused by an obstruction in the urinary tract, which may be due to BPH. Obstruction is the most serious complication of BPH and requires medical attention. Voiding symptoms include:

- A hesitation before urine flow starts despite the urgency to urinate

- Straining when urinating

- Weak or intermittent urinary stream

- A sense that the bladder has not emptied completely

- Dribbling at the end of urination or leakage afterward

- Inability to urinate

Storage (Irritative) Symptoms

Storage symptoms, also referred to as filling symptoms, include:

- An increased frequency of urination (every few hours).

- An urgent need to urinate and difficulty postponing urination.

- Discomfort when urinating.

- Frequent night-time urination, or nocturia, is one of the most publicized symptoms of BPH, but it's also one of the trickiest, since many if not most cases of nocturia are not caused by BPH but by other conditions.

Urine flows from the kidney through the ureters into the urinary bladder where it is temporarily stored. As the bladder becomes distended with urine, nerve impulses from the bladder signal the brain that it is full, giving the individual the urge to void. By voluntarily relaxing the sphincter muscle around the urethra, the bladder can be emptied of urine. Urine then flows out through the urethra.

Serious Complications

Acute urinary retention (inability to void) is a serious complication of severe BPH that requires immediate medical attention. Urinary retention can be a sign of obstruction in the bladder.

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is a blockage at the base of the bladder that reduces or prevents the flow of urine into the urethra, the tube that carries urine out of the body. BPH is a common cause of this condition.

Even without complete obstruction, urinary retention can increase the risk for other complications including:

- Urinary tract infections (if urine does not empty completely from the bladder, bacteria can grow)

- Kidney damage (urinary tract infections can lead to kidney infections; bladder obstruction can lead to kidney failure)

- Bladder damage (the pressure exerted by retained urine can stretch and weaken the bladder walls; this can develop into urinary incontinence or an inability to empty your the bladder completely)

- Bladder stones (urine left in bladder can crystalize and form bladder stones)

- Diagnosis

A doctor makes a diagnosis of BPH based on description of symptoms, medical history, physical examination, and various blood and urine tests. If necessary, your doctor may refer you to a urologist for more complex test procedures.

Some diagnostic tests are used to rule out cancers of the prostate or bladder as the cause of symptoms. In some cases, symptoms of prostate cancer can be similar to those of BPH. Tests may also be performed to see if BPH has caused any kidney damage.

Medical History

The doctor will ask about your personal and family medical history, including past and present medical conditions. The doctor will also ask about any medications you are taking that could cause urinary problems.

Physical Examination

Digital Rectal Exam

The digital rectal exam is used to detect signs of prostate cancer. The doctor inserts a gloved and lubricated finger into the patient's rectum and feels the prostate to estimate its size and to detect nodules or tenderness. The size of the prostate is not always associated with severity of symptoms. The exam is quick and painless. The test helps rule out prostate cancer or problems with the muscles in the rectum that might be causing symptoms, but it can underestimate the prostate size. It is never the sole diagnostic tool for either BPH or prostate cancer.

Other Physical Examinations

The doctor will press and manipulate (palpate) the abdomen and sides to detect signs of kidney or bladder abnormalities. The doctor may test reflexes, sensations, and motor response in the lower body to rule out possible nerve-related (neurologic) causes of bladder dysfunction.

Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) Test

Your doctor may recommend a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test to check for prostate cancer. PSA is a substance made by cancerous and non-cancerous prostate cells. A PSA test measures the level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the blood. The PSA test is a widely used but controversial screening test for prostate cancer. High PSA levels may indicate prostate cancer, but BPH itself often raises PSA levels. And, some drugs used to treat BPH can decrease PSA levels.

Urinalysis

A urinalysis can detect signs of bleeding or infection. Another urine test, urine cytology, can help detect bladder cancer.

Uroflowmetry

To determine whether the bladder is obstructed, an electronic test called uroflowmetry measures the speed of urine flow. To perform this test, the patient urinates into a special toilet equipped with a measuring device. A reduced flow may indicate BPH. However, bladder obstruction can also be caused by other conditions including weak bladder muscles and problems in the urethra. A strong flow may not rule out obstruction because the bladder may squeeze more forcefully to get the urine out and preserve the speed of flow.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy, also called urethrocystoscopy or cystourethroscopy, is a test performed by a urologist to check for problems in the lower urinary tract, including the urethra and bladder. The doctor can determine the presence of structural problems including enlargement of the prostate, obstruction of the urethra or neck of the bladder, anatomical abnormalities, or bladder stones. The test may also identify bladder cancer, causes of blood in the urine, and infection.

In this procedure, a thin tube with a light at the end (cytoscope) is inserted into the bladder through the urethra. The doctor may insert tiny instruments through the cytoscope to take small tissue samples (biopsies). Cytoscopy is typically performed as an outpatient procedure, usually in the office. The person may also be given sedation and local, spinal, or general anesthesia, typically in an outpatient surgical setting.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a painless procedure that can give an accurate picture of the size and shape of the prostate gland. Ultrasound may also be used for detecting kidney damage, tumors, and bladder stones. Ultrasound tests of the prostate generally use one of two methods:

- Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) uses a rectal probe for assessing the prostate. TRUS is significantly more accurate for determining prostate volume.

- Transabdominal ultrasonography uses a device placed over the abdomen. It can give an accurate measure of postvoid residual urine and can be used to check for kidney damage caused by severe BPH.

Postvoid Residual Urine

The postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) test measures the amount of urine left after urination. Normally, about 50 mL or less of urine is left; more than 200 mL is a sign of abnormalities. Measurements in between require further tests. The most common method for measuring PVR is with a bladder scanner. This is a type of ultrasound that measures the amount of urine inside the bladder. If a scanner is not available, a small tube called a catheter may need to be passed into the bladder to drain any urine left behind and measure the amount.

Ruling Out Other Causes of Symptoms

In addition to prostate cancer, other conditions and factors can cause lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) similar to those associated with BPH:

- Structural Abnormalities. Abnormalities in the urinary tract can cause BPH-like symptoms. These abnormalities include narrowing of the urethra and weakened bladder muscle. Such conditions can produce obstruction, impair or weaken the detrusor muscle surrounding the bladder, or cause other damage that impacts the urinary tract.

- Prostatitis. Prostatitis is an inflammation of the prostate gland that can be caused by bacterial or nonbacterial factors. Symptoms include urgent need to urinate, frequent urination, and the need to urinate at night. Pain may occur in the lower back or rectum, or it may develop after ejaculation.

- Overactive Bladder. Overactive bladder (OAB) is marked by a need to urinate frequently or urgently. In some cases, it may lead to urinary incontinence. It most commonly affects women, but can affect men as well. It is possible for men to have both OAB and BPH.

- Neurological Conditions. Neurological conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson disease can affect the bladder's ability to function normally.

- Urinary Tract Infections. Untreated urinary tract infections (UTIs) can cause symptoms associated with LUTS.

- Medications. Many medications can cause LUTS or urinary retention, and can worsen symptoms of BPH. These types of medications include antihistamines, decongestants, diuretics, opiates, and tricyclic antidepressants.

- Treatment

Treatment for BPH depends in part on the severity of symptoms. Men who have few or minimal symptoms may consider trying a period of "watchful waiting" before choosing a drug or surgical treatment:

- Watchful Waiting. Watchful waiting (also known as active surveillance) involves lifestyle changes and an annual examination. (Even when choosing watchful waiting, it is important to have a doctor perform an initial examination to rule out other disorders.) Your doctor will monitor your condition to determine when it may be time to start treatment.

- Treatment. The primary goals of treatment for BPH are to improve urinary flow and to reduce symptoms. Many options are available. They include drug therapies to help shrink or relax the prostate, minimally invasive procedures that reduce excess prostate tissue, and surgery to remove part of the prostate.

Deciding Between Treatment and Watchful Waiting

The choice between watchful waiting and treatment often depends on symptom severity. The American Urological Association's BPH Symptom Score uses seven questions to evaluate a patient's urinary symptoms during the past month. (The International Prostate Symptoms Score is another index that is also used.) The questions are:

- How often have you had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finished urinating?

- How often have you had to urinate again less than 2 hours after you finished urinating?

- How often have you stopped and started again several times when you urinated?

- How often have you found it difficult to urinate?

- How often have you had a weak urinary stream?

- How often have you had to push or strain to begin urination?

- How many times did you most typically get up to urinate from the time you went to bed at night until the time you got up in the morning?

Responses for the first six questions are on a scale from "not at all" to "almost always." (The last question uses answers ranging from "none" to "5 or more times.") Each response is assigned a number on a scale of 0 to 5. The total symptom score can fall anywhere between 0 and 35.

People with mild symptoms will have low scores and may decide to delay treatment. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. Treatment can reduce the score:

- A score reduction of up to 5 points indicates modest symptom relief

- A score reduction of 5 to 10 points indicates moderate symptom relief

- A score reduction of more than 10 points indicates large symptom relief

Your doctor can discuss with you the various treatment options and the likelihood of symptom relief they may provide. All treatments have various side effects, which need to be taken into consideration. Quality of life is as important as symptom severity.

Treatment Options

Medications

In general, there is no reason to treat BPH with medications unless symptoms become very bothersome. The size of the prostate, determined by exam or ultrasound, cannot indicate the need for medications. Evidence suggests that:

- Medications are the best choice for men with mild-to-moderate symptoms who want treatment. Choices include alpha-blockers, anti-androgens, or a combination of the two. Specific factors indicate the best choice, although most men take an alpha-blocker.

- Men with moderate-to-severe symptoms often respond to the same medications as men with mild symptoms. Recent developments in drug therapy have reduced or delayed the need for surgery.

Surgery

Surgery is an option for men with moderate-to-severe symptoms who have not been helped by medication. There are many types of surgical treatment for BPH. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is the standard procedure, but less invasive procedures, particularly those using heat or lasers to destroy prostate tissue, are becoming more common.

The most common reason for choosing surgery is obstruction of the bladder outlet caused by an enlarged prostate, which causes slowing of urinary stream or even urinary retention. Surgery may also be a reasonable option when BPH is clearly related to one or more of the following conditions:

- Recurrent urinary tract infection.

- Blood in the urine (hematuria). The drug finasteride may help some men with this condition and is a treatment option before surgery.

- Bladder stones.

- Kidney problems.

- Moderate-to-severe symptoms that are not well controlled with medications.

Increased urinary flow and reduced urine retention are the greatest improvements resulting from surgery. Often, however, the benefits of surgery are not necessarily permanent, as the prostate can regrow.

- Lifestyle Changes

General Lifestyle Recommendations

Certain lifestyle changes may help relieve symptoms and are particularly important for men who choose to avoid surgery or drug therapy. They include:

- Limiting daily fluid intake to less than 2,000 mL (about 2 quarts).

- Limiting or avoiding alcohol and caffeine.

- Limiting beverages in the evening. Avoiding drinking fluids after your evening meal.

- Trying to urinate at least once every 3 hours.

- "Double-voiding" may be helpful -- after urinating, wait and try to urinate again.

- Staying active. Cold weather and immobility may increase the risk for urine retention. Keeping warm and exercising may help.

- Trying to achieve and maintain a healthy weight. Obesity and lack of physical activity increase the risk for lower urinary tract symptoms.

Avoiding Medications that Aggravate Symptoms

Decongestants and Antihistamines

Men with BPH should avoid any medications for colds and allergies that contain decongestants, such as pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, generic). Such drugs, known as adrenergics, can worsen urinary symptoms by preventing muscles in the prostate and bladder neck from relaxing to allow urine to flow freely. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl, generic), can also slow urine flow in some men with BPH.

Diuretics

Diuretics are drugs that increase urine production by the kidneys. They are often used to treat high blood pressure. If you take a diuretic, you may want to talk to your doctor about reducing the dosage or switching to another type of drug. No one should stop taking a diuretic without medical supervision.

Other Drugs

Other drugs that may worsen symptoms are certain antidepressants and drugs used to treat spasticity.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training

Pelvic floor muscle exercises, also called Kegel exercises, may help men prevent urine leakage, particularly after surgical procedures. These exercises strengthen the pelvic floor muscles that both support the bladder and close the sphincter.

Performing the Exercises

Since the pelvic floor muscles are internal and sometimes hard to isolate, doctors often recommend practicing while urinating:

- Contract the muscle until the flow of urine is slowed or stopped. Attempt to hold each contraction for 20 seconds.

- Release the contraction.

- In general, people should perform 5 to 15 contractions, 3 to 5 times daily.

- Once you are comfortable with pelvic floor exercises, it is best NOT to practice while urinating.

Dietary Factors

Dietary factors do not appear to play much of a role in BPH risk or severity. Still, because obesity and high body mass index (BMI) are possible risk factors, good nutrition is important. A heart-healthy diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains -- along with regular physical activity -- can help with weight control and reduce BPH risk.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need approval from the FDA to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been several reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. People should check with their doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Popular herbal and dietary supplement treatments for BPH include:

- Saw palmetto, one of the most popular herbal remedies for BPH. It comes from the berry of the plant Serenoa repens. Most clinical trials have shown a very small effect or no benefit at all. A large, high-quality study found that saw palmetto did not help men with moderate-to-severe BPH even if the herb was taken for 1 year. Another high-quality study found that saw palmetto had no benefit even when the dose was tripled.

- Extracts from African plum tree (Pygeum africanum), rye grass pollen (Secale cereale), stinging nettle root (Urtica dioica), South African star grass (Hypoxis rooperi), and pumpkin seed oil (Cucurbita peponis).

- Beta-sitosterol, a plant sterol found in some dietary supplements marketed for prostate health.

- There is no scientific evidence that any of these remedies help treat BPH.

People should be aware that high doses of zinc supplements may increase the risk and progression of BPH.

- Medications

The two main drug classes used for BPH are:

- Alpha-blockers. These drugs relax smooth muscles, largely in the bladder neck and prostate. They include terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), tamsulosin (Flomax), alfuzosin (Uroxatral), and silodosin (Rapaflo). Alpha-blockers help relieve BPH symptoms, but they do not reduce the size of the prostate. They can help improve urine flow and reduce risk for bladder obstruction. Alpha-blockers are often the first medication choice.

- 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs). Finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart) block the conversion of testosterone to DHT, the male hormone that stimulates the prostate. These drugs are helpful for men with significantly enlarged prostates. In addition to relieving symptoms, they increase urinary flow and may even help shrink the prostate. However, people may have to take these drugs for up to 6 to 12 months to achieve full benefits.

- Jalyn is a combination medication that includes both tamsulosin (alpha-blocker) and dutasteride (5-ARI).

Because alpha-blockers and 5-ARIs work in different ways, some patients find that a combination of the two controls symptoms better than a single drug alone. Other men find that a single drug is adequate for symptom control.

Alpha-Blockers

Alpha-adrenergic antagonists, commonly called alpha-blockers, relax smooth muscles in the prostate and make it easier for urine to flow. They quickly improve symptoms, usually within days. Because these drugs are short-acting, symptoms return once a man stops taking the medication. Alpha-blockers do not shrink the size of the prostate or change PSA levels.

Alpha-blockers are generally referred to as either nonselective or selective:

- Terazosin (Hytrin) and doxazosin (Cardura) are the nonselective alpha-blockers used for BPH treatment. Nonselective alpha-blockers relax all smooth muscles in the body that surround blood vessels. Because of this, they can lower blood pressure, sometimes causing side effects such as lightheadedness or even fainting.

- Tamsulosin (Flomax, Jalyn), alfuzosin (Uroxatral), and silodosin (Rapaflo) are the selective alpha1-blockers used for BPH. Selective alpha-blockers target more specifically the smooth muscles of the prostate, but they can also affect other areas of the body, such as the eyes. They have fewer side effects than nonselective alpha blockers and are now prescribed much more often than the older drugs.

Side Effects

Alpha-blockers can cause headache, and stuffy or runny nose. Alpha-blockers can reduce blood pressure, which may cause dizziness, lightheadedness, and fainting. Orthostatic hypotension, a sudden drop in blood pressure when standing, can occur and increases the risk of falling. Taking the medication close to bedtime can help reduce these side effects.

Because of the reduced blood pressure side effect, do not take nonselective alpha blockers with the phosphodiesterase (PDE5) inhibitors used for erectile dysfunction such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), vardenafil (Levitra), or avanafil (Stendra). Men who take selective alpha blockers may be able to use erectile dysfunction pills with guidance from a doctor. (Men may experience a decreased ejaculate while taking these drugs. However, erectile dysfunction is not a usual side effect of alpha-blockers, as it is with finasteride and dutasteride.)

A special concern for tamsulosin, and other selective alpha-blockers, is that they are associated with a condition called intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). IFIS is a loss of muscle tone in the iris that can cause complications during cataract surgery. People who are planning cataract or other eye surgery should be sure to inform their doctors prior to the surgery. IFIS appears more likely to occur with selective alpha-blockers than nonselective alpha blockers.

Some research suggests that tamsulosin may double the risk for low blood pressure (hypotension) severe enough to require hospitalization. The risk appears to be highest in the first 8 weeks after starting or restarting treatment with the drug.

5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitors (5-ARIs)

The prostate gland contains an enzyme called 5 alpha-reductase, which converts testosterone to another androgen called dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Drugs known as 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) block this enzyme and thus reduce DHT in the prostate thereby preventing prostate growth.

The 5-ARIs used for treating BPH are:

- Finasteride (Proscar)

- Dutasteride (Avodart, Jalyn [Jalyn is a 2-in-1 pill that combines dutasteride with the alpha-blocker Tamsulosin])

Because 5-ARIs help shrink enlarged prostates, they are most effective in reducing symptoms in men with very large prostates. These drugs take several months before they have an effect so men may not notice any signs of improvement for 3 to 6 months and full effect may not be reached for 12 months.

The FDA recommends that doctors rule out other urologic conditions, including prostate cancer, which may mimic BPH before prescribing 5-ARIs for BPH treatment.

Side Effects

Finasteride and dutasteride can cause erectile dysfunction, lowered sexual drive (libido), and ejaculation and orgasm disorders. These drugs can reduce the volume and quality of semen released during ejaculation. These sexual side effects may sometimes persist even after the drug is discontinued. (A positive side effect of finasteride is possible reduction of hair loss related to male hormones and, in some cases, improvement of hair growth in men with mild-to-moderate male pattern baldness.)

These drugs decrease prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, which may mask the presence of prostate cancer. To resolve this problem, doctors estimate PSA levels in men taking these drugs by doubling the measured PSA values. The FDA advises doctors that an increase in PSA (even if it's in a normal range) while taking this drug may indicate the presence of prostate cancer.

A controversial matter is whether 5-ARIs help protect against prostate cancer. Studies have suggested that 5-ARIs lower a man's overall risk for developing prostate cancer. However, the FDA advised in the past that these drugs may increase the risk of developing high-grade aggressive types of prostate cancer. Most recent evidence does not indicate an increased risk for cancer with these medicines. They should not be used for prostate cancer prevention.

Other Drugs

Anticholinergic drugs, also called antimuscarinics, such as tolterodine (Detrol) may be helpful for some patients. For treatment of BPH, they may be prescribed either alone or in combination with an alpha-blocker drug. They are more likely to help men with frequency, urgency, nocturia, and incontinence caused by an overactive bladder.

Tadalafil (Cialis) is approved for treating BPH either alone or when it occurs along with erectile dysfunction. Tadalafil should not be used in combination with alpha-blockers without careful consideration and monitoring for excessive blood pressure lowering. Like all PDE5 inhibitor drugs used for erectile dysfunction, men who take nitrate drugs should not take tadalafil.

- Surgery

Several surgical approaches are used to treat BPH. Reasons for performing prostate surgery include:

- Persistent or recurrent episodes of urinary retention (inability to urinate)

- Persistent blood in the urine

- Bladder stones

- Moderate or severe lower urinary tract symptoms that do not improve with medication

- Kidney failure from inability to empty the bladder

- Repeated urinary tract infections

Surgical options include invasive and minimally invasive procedures. The choice of which surgical procedure to use depends on various factors, including a man's age, size of the prostate, and general health.

The most effective surgical procedure, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), is also the most invasive and has the highest risk for serious complications, though the overall risk of major complications is low. However, because it is more effective than less invasive procedures, TURP remains the procedure of choice for many doctors.

Minimally invasive procedures use laser or some other form of heat to destroy excess prostate tissue. Although minimally invasive procedures may be an appropriate choice for some people, including younger men, none to date have proven superior to TURP.

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) involves surgical removal of the inner portion of the prostate, where BPH develops. It is the most common surgical procedure for BPH, although the number of procedures has dropped significantly over the past decades because of the increased use of effective medications and the increasing use of alternate procedures.

Procedure

The surgeon inserts a thin fiber-optic tube called a resectoscope into the urethra. No incision or stitches are needed. The resectoscope is a type of endoscope. It has a telescope lens to help the surgeon see the prostate gland. The surgeon uses a wire cutting loop inserted into the resectoscope to cut away excess prostatic tissue using a monopolar electrocautery, and fluid irrigation solutions (water or glycin) are used to flush away the excised matter. TURP can be done as an outpatient procedure but may require a 1 to 2 day hospital stay. A newer version called bipolar TURP uses a bipolar electrocautery instead which allows the use of saline as the irrigation solution.

A Foley catheter generally remains in place for 1 to 3 days after surgery to allow urination. This device is a tube inserted through the opening of the penis to drain the urine into a bag. The catheter can cause temporary bladder spasms that can be painful. The catheter may be removed while the person is in the hospital or after they are sent home.

Recuperation

Urine flow is stronger almost immediately after most TURP procedures. After the catheter is removed, people often feel some pain or sense of urgency as the urine passes over the surgical wound. These sensations generally last for about a week and then gradually subside. Complete healing takes about 2 months. The following are some tips for speeding recovery and avoiding complications:

- During recuperation avoid driving, operating heavy equipment, lifting, sudden movements, and straining the muscles in the lower tracts, such as during a bowel movement.

- Drinking at least 4 to 8 glasses of water a day after surgery is important to flush the bladder and help healing.

- Foods that help prevent constipation, such as fruits and vegetables, are important. A laxative may be needed if constipation occurs.

- Pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises can help reduce incontinence. Performing 3 to 4 sets of 30 contractions daily is recommended.

- Don't resume sexual activity until your doctor says it is safe to do so.

- Check with your doctor about any drugs or herbal supplements that you take to make sure that they will not thin blood and increase bleeding.

Complications

The TURP procedure is generally safe but there are some risks for short- and long-term complications.

Immediate short-term complications after surgery may include:

- Bleeding. Some blood in the urine is normal after TURP surgery but persistent heavy bleeding or clotting is a sign of a more serious complication. In rare cases, if the bleeding is very heavy, patients require blood transfusions. This complication is less common with bipolar TURP.

- Infection. Urinary tract infections are more likely to occur the longer the catheter is in place.

- Urination problems. Temporary urinary leaking or dribbling (urinary incontinence) is common after surgery and often resolves within a month. Temporary inability to urinate (urinary retention) may occur for a few days following surgery, which is why a catheter is used to help remove urine.

- TURP syndrome. If the fluids used during TURP build up, water intoxication can develop, which can be serious. TURP syndrome occurs in a very small percentage of patients and can be treated with diuretics to remove excess fluid. This complication is avoided with bipolar TURP as saline irrigation can be used instead.

Long-term complications after surgery may include:

- Loss of ejaculation. Retrograde ejaculation, also called dry orgasm is very common, if not the rule after TURP. With this condition, the semen is ejaculated into the bladder rather than out through the urethra. Retrograde ejaculation does not affect sexual pleasure, but it does impair fertility.

- Erectile dysfunction.Erectile dysfunction, the inability to achieve or maintain an erection, can occur rarely after TURP.

- Urinary incontinence. Temporary urinary incontinence is common after TURP but in rare cases some men become completely unable to hold back their urine.

- Repeat surgery. Up to 10% of people who undergo TURP need a repeat operation within 5 years. Sometimes, scarring in the prostate severe enough to cause obstruction occurs within a year of the procedure and may require transurethral incision (TUIP) or repeat resection. More often, the urethra is scarred and narrows, but usually this condition can be corrected by a simple stretching procedure performed in the doctor's office. Sometimes, this requires a small internal cut in the urethra to open it up.

Other Invasive Surgical Procedures

Transurethral Incision of the Prostate (TUIP)

In TUIP, the surgeon makes only one or two incisions in the prostate, causing the bladder neck and the prostate to spring open and reduce pressure on the urethra. TUIP is generally reserved for men with minimally enlarged prostates who have obstruction of the neck of the bladder.

TUIP is less invasive than TURP, has a lower rate of the same complications (particularly retrograde ejaculation), and usually does not require a hospital stay. More studies are still needed, however, to determine whether they are comparative in long-term effectiveness.

Simple Prostatectomy

In simple prostatectomy, the enlarged prostate is removed through an open incision in the abdomen using standard surgical techniques. This is major surgery and requires a hospital stay of several days. Simple prostatectomy is used only for severe cases of BPH, when the prostate is severely enlarged, the bladder is damaged, there are many stones or one large stone in the bladder, or other serious problems exist. Some people need a second operation because of scarring. Side effects of simple prostatectomy can include erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence. This surgery can be performed through an incision in the lower abdomen or keyhole incisions for robot-assisted laparoscopy.

Laser Surgery

Procedures

Laser technology is used for removal of prostate tissue. Laser procedures can mostly be done on an outpatient basis, and there is little risk for bleeding. The procedure involves passing a small tube with a tiny camera and the laser fiber through the urethra of the penis. The procedure is performed under spinal, epidural, or general anesthesia.

Laser procedures have a faster recovery time and less risk of incontinence than invasive surgical procedures, but their long-term effectiveness is less clear. Laser surgery may not be appropriate for men with larger prostates. The procedures use various forms of heat to destroy cells with mechanisms that range from coagulation to complete vaporization:

- Transurethral holmium laser ablation of the prostate (HoLAP) uses laser energy to target and vaporize obstructing prostate tissue. The removal of the tissue helps to restore urine flow.

- Transurethral holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) is similar to HoLAP except a portion of the prostate is cut into smaller pieces and then flushed out from the bladder.

- Photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP) uses a potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) laser ("green-light" laser) to vaporize prostate tissue. The procedure may be a better option for men taking anticoagulant ("blood thinner") medication. Improvement lasts for up to 1 year after the procedure. More studies are needed to confirm long-term efficacy.

Other Less Invasive Procedures

These minimally invasive procedures carry fewer risks for incontinence or problems with sexual function than invasive procedures, but it is unclear how effective they are in the long term.

Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy (TUMT)

Transurethral microwave thermotherapy delivers heat using microwave pulses to destroy prostate tissue. A microwave antenna is inserted through the urethra with ultrasound used to position it accurately. The antenna is enclosed in a cooling tube to protect the lining of the urethra. Computer-generated microwaves pulse through the antenna to heat and destroy prostate tissue. When the temperature becomes too high, the computer shuts down the heat and resumes treatment when a safe level has been reached. The procedure takes 30 minutes to 2 hours, and the patient can go home immediately afterward.

Transurethral Needle Ablation (TUNA)

Transurethral needle ablation is a relatively simple and safe procedure, using needles to deliver high-frequency radio waves to heat and destroy prostate tissue.

Transurethral Electrovaporization (TUVP)

Transurethral electrovaporization uses high voltage electrical current delivered through a resectoscope to combine vaporization of prostate tissue and coagulation that seals the blood and lymph vessels around the area. Deprived of blood, the excess tissue dies and is sloughed off over time.

Water Vapor Thermal Therapy (Rezum)

In this procedure, small amounts of steam are delivered through a transurethral needle to destroy prostate tissue. The destroyed tissue is then broken down by the body over the next 6 weeks leaving a wider passageway. The procedure takes between 5 to 10 minutes. A catheter is left in place for 2 to 5 days afterwards. There is virtually no risk of retrograde ejaculation.

Prostatic Implants

Prostatic implants such as UroLift or iTind are used to treat men ages 45 and older with BPH. The implants are placed during a minimally invasive procedure and help to keep the lobes of the enlarged prostate gland open to improve urine flow. It appears to have less impact on sexual health than other surgical procedures.

- Resources

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases -- www.niddk.nih.gov

- American Urological Association -- www.auanet.org

- Urology Care Foundation -- www.urologyhealth.org

References

Andersson KE, Wein AJ. Pharmacologic management of lower urinary tract storage and emptying failure. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 120.

Capogrosso P, Salonia A, Montorsi F. Evaluation and nonsurgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 145.

Foster HE, Barry MJ, Dahm P, et al. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2018;200(3):612-619. PMID: 29775639 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29775639/.

Helo S, Welliver RC, McVary KT. Minimally invasive and endoscopic management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 146.

Jones P, Rai BP, Nair R, Somani BK. Current status of prostate artery embolization for lower urinary tract symptoms: review of world literature. Urology. 2015;86(4):676-681. PMID: 26238328 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26238328/.

Kaplan SA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatitis. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 120.

Kim EH, Larson JA, Andriole GL. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:137-151. PMID: 26331999 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26331999/.

Langan RC. Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Prim Care. 2019;46(2):223-232. PMID: 31030823 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31030823/.

Madersbacher S, Roehrborn CG, Oelke M. The role of novel minimally invasive treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2020;126(3):317-326. PMID: 32599656 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32599656/.

McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, et al. Update on AUA guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2011;185(5):1793-1803. PMID: 21420124 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21420124/.

Mock S, Dmochowski R. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and related entities. In: Hanno PM, Guzzo TJ, Malkowicz SB, Wein AJ, eds. Penn Clinical Manual of Urology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:chap 15.

Parsons JK, Dahm P, Köhler TS, Lerner LB, Wilt TJ. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline amendment 2020. J Urol. 2020;204(4):799-804. PMID: 32698710 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32698710/.

Pattanaik S, Mavuduru RS, Panda A, et al. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors for lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD010060. PMID: 30480763 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30480763/.

Powell T, Kellner D, Ayyagari R. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical manifestations, imaging, and patient selection for prostate artery embolization. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;23(3):100688PMID: 33308530 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33308530/.

Roehrborn CG, Strand DW. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: etiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology, and natural history. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 144.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901-1913. PMID: 29801017 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29801017/.