Anemia - InDepth

Iron deficiency - InDepth; Pernicious anemia - InDepthAn in-depth report on the types, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of anemia.

- Highlights

Overview

Anemia is the name applied to many different conditions that are all characterized by an abnormally low number of healthy red blood cells. Red blood cells carry oxygen from the lungs to tissues with the help of hemoglobin, a red blood cell protein that attaches to oxygen. Anemia is diagnosed when the hemoglobin level is low. This occurs because there are too few red blood cells or their shape or function is abnormal. There are many different causes and types of anemia.

Iron-deficiency anemia, the most common type, is usually treated with dietary changes and iron supplement pills. Other types of anemia, such as those associated with chronic diseases or cancer, may need more aggressive treatment.

Preventing Iron Deficiency in Infants and Toddlers

The American Academy of Pediatrics' guidelines for preventing iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in infants and young children include:

- Full-term infants who are healthy and exclusively breastfed should receive an oral iron supplement beginning at 4 months of age. The supplement should be continued until iron-containing solid foods, such as cereals, are introduced. Breast milk contains very little iron, but most healthy babies are born with iron stores sufficient for their first 4 months.

- Preterm infants who are breastfed should receive an iron supplement by 1 month of age.

- Formula-fed infants get adequate iron from iron-fortified formula. For all babies, cow's milk should not be introduced before age 12 months.

- Toddlers ages 1 to 3 years should get their iron from foods such as red meats, iron-rich vegetables, and fruits that are rich in vitamin C. (Vitamin C helps boost iron absorption.)

- Introduction

Anemia is a condition in which the body does not have enough healthy red blood cells. Red blood cells provide oxygen to body tissues with the help of hemoglobin, a red blood cell protein that attaches to oxygen in the lungs. People with anemia have a lower than normal hemoglobin level.

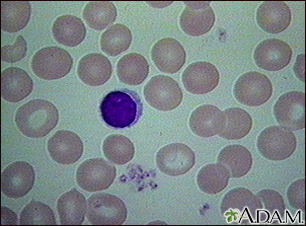

Image of normal red blood cells (RBCs) as seen in the microscope after staining.

Anemia is not a single disease but a condition, like fever, with many possible causes and many forms.

Causes of anemia include nutritional deficiencies, medication-related side effects, or chronic diseases that cause bleeding or interfere with the production of red blood cells. The condition may be temporary (such as in acute blood loss) or long-term, and can manifest in mild or severe forms.

Anemia can also be caused by genetic (inherited) blood disorders such as sickle cell disease that damage the shape of the red blood cell.

This report focuses on the most common forms of anemia:

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Anemia of chronic disease (also known as anemia of inflammation)

- Treatment-related anemia (chemotherapy, medication, and radiation therapy)

- Megaloblastic anemia (caused by deficiencies in the B vitamins folate, vitamin B12, or both)

Blood

Blood is composed of about 55% plasma and 45% blood cells. It has 4 components:

- Plasma is a clear yellowish liquid that contains water, proteins, salt, and other substances. Plasma helps carry nutrients and hormones through the body and remove cellular waste products.

- Platelets (thrombocytes) are small cell fragments that are necessary for blood clotting.

- White blood cells (leukocytes) are the body's infection fighters. They account for about 1% of total blood volume.

- Red blood cells (erythrocytes) comprise the majority of blood cells and are the most important factors in anemia.

Red blood cells (RBCs), also known as erythrocytes, carry oxygen throughout the body to nourish tissues and sustain life. Red blood cells are the most abundant cells in our bodies. On average, men have about 5.2 million red blood cells per cubic millimeter of blood, and women have about 4.7 million per cubic millimeter of blood.

Hemoglobin and Iron

Each red blood cell contains 280 million hemoglobin molecules. Hemoglobin is the most important component of red blood cells. It is composed of 4 protein subunits (globulin) bound to a heme group, which contains iron.

In the lungs, the heme component binds to oxygen in exchange for carbon dioxide. The oxygenated hemoglobin in red blood cells is then transported to the body's tissues, where it releases the oxygen in exchange for carbon dioxide, and the cycle repeats. The oxygen is used in the mitochondria, the power source within all cells. Iron necessary in the formation of hemoglobin comes primarily from:

- Food absorption in the gut

- Breakdown of old red blood cells

- Iron stores in organs such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow

Red Blood Cell Production (Erythropoiesis)

The actual process of making red blood cells is called erythropoiesis. (In Greek, erythro means "red," and poiesis means "to make.") The process of manufacturing, recycling, and regulating the number of red blood cells is complex and involves many parts of the body:

- The body carefully regulates its production of red blood cells so that enough are manufactured to carry oxygen but not so many that the blood becomes thick or sticky (viscous).

- Most of the work of erythropoiesis occurs in the bone marrow. Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hormone essential for red blood cell production. Kidneys produce EPO, which stimulate the bone marrow to manufacture more red blood cells.

- The lifespan of a red blood cell is 90 to 120 days. Old red blood cells are removed from the blood by the liver and spleen.

- When old red blood cells are broken down for removal, iron is returned to the bone marrow to make new cells.

- Causes

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Iron deficiency anemia occurs when the body lacks mineral iron to produce the hemoglobin it needs to make red blood cells.

Iron deficiency anemia results when the body's iron stores run low. This can happen because:

- You lose more blood cells and iron than your body can replace

- Your body does not do a good job of absorbing iron

- Your body is able to absorb iron, but you are not eating enough foods that contain iron

- Your body needs more iron than normal (such as if you are pregnant or breastfeeding)

A number of medical conditions can cause iron deficiency anemia.

Chronic Blood Loss

Iron deficiencies most commonly occur from internal blood loss due to other medical conditions. These conditions include:

- Very heavy periods (menorrhagia), the most common causes of anemia in menstruating women, which may be caused by uterine fibroids or endometriosis

- Peptic ulcers, which may be caused by H pylori infections, or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen

- Colon, stomach, and esophageal cancer

- Bleeding from esophageal varices, common in people with alcohol use disorder

Impaired Absorption of Iron

Impaired absorption of iron can be caused by:

- Certain intestinal diseases (inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease)

- Surgical procedures, particularly those involving removal of parts of the stomach and small intestine

- Intestinal infections, such as hookworm and other parasites

- In children, consuming too much cow's milk, which can interfere with iron absorption

Inadequate Iron Intake

A healthy diet easily provides enough iron. In general, most people need just 1 mg of extra iron each day. (Menstruating women need 2 mg each day.) However, certain people are at risk for lack of iron in their diets. They include vegetarians and others who do not consume enough iron-rich foods, young children and pregnant women who have higher iron needs, and anyone who has a medical condition that places the risk for iron deficiency.

Anemia of Chronic Disease

Anemia of chronic disease is associated with a wide variety of chronic conditions that reduce the production and survival of red blood cells. These diseases include:

- Cancers, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease.

- Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and celiac disease.

- Chronic kidney disease and renal failure.

- Inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Long-term infections such as chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections, osteomyelitis, HIV/AIDS.

- Chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis C and cirrhosis.

- Endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism.

Most of these conditions are associated with chronic inflammation. It has recently been demonstrated that anemia in chronic inflammation is caused by increases in the levels of hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism. Hepcidin blocks the absorption of iron from the gut, and the exit of iron from cells called macrophages. Macrophages help in the breakdown of old red blood cells. Thus, when inflammation causes hepcidin levels to be high, iron levels in the blood are low, even though iron stored in macrophages is high.

Treatment-Related Anemia

Several medications and treatments can cause anemia in different ways, including accelerated destruction of red blood cells or toxic effects on the bone marrow or kidney. Examples include chemotherapy or radiotherapy for cancer, some antibiotics, and medications for transplants, seizures, or HIV infection.

Megaloblastic Anemia and Pernicious Anemia

Megaloblastic anemia

Caused by deficiencies in the B vitamins folate or vitamin B12 (also called cobalamin). Such deficiencies produce abnormally large (megaloblastic) red blood cells that have a shortened lifespan.

Pernicious anemia

A type of vitamin B12 anemia. It is considered an autoimmune disease. The body's immune system attacks the production of a special protein, called intrinsic factor (IF), which helps the intestines absorb vitamin B12. This protein is released by cells in the stomach. When the stomach does not make enough intrinsic factor, the intestine cannot properly absorb vitamin B12, and anemia occurs.

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Usually caused by insufficient intake but can also be caused by a weakened stomach lining (atrophic gastritis) or as a result of gastrointestinal surgery. Nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency can occur in vegetarians and vegans or in cases of poor nutrition. The main dietary sources for vitamin B12 are meat, poultry, shellfish, eggs, and dairy products. Some cereals and soy-based foods are fortified with B12. Neurologic problems can result from prolonged vitamin B12 deficiency.

Folate deficiency can also be caused by poor diet. Alcohol use disorders can compound the effects of malnutrition.

Medical conditions that impair the small intestine's absorption ability can cause folate deficiency. These disorders include celiac disease (a sensitivity reaction to gluten) and Crohn disease (an inflammatory bowel disorder).

Other causes of anemia may not be related to nutritional deficiencies or chronic diseases. Such causes are less common, but include leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative disorders, hemolytic anemia, and hypersplenism.

- Risk Factors

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional disorder and also the most common cause of anemia worldwide. Around a quarter of the global population have anemia, and iron deficiency accounts for about one half of the world's anemia burden. For iron deficiency anemia, young children have the highest risk followed by premenopausal women. Adolescent and adult men and postmenopausal women have the lowest risk. Men are actually more at risk for iron overload, probably because of their higher meat intake and minimal iron loss.

Risk Factors in Infants and Children

Iron deficiency is the most common cause in children, but other forms of anemia, including hereditary blood disorders, can also cause anemia in this population. In the United States, approximately 9% of children ages 1 to 3 years are iron-deficient, and about 30% of this group progress to anemia.

Children need to absorb an average of 1 mg per day of iron to keep up with the needs of their growing bodies. Since children only absorb about 10% of the iron they eat, most children need to receive 8 to 10 mg of iron per day. Breast milk contains very little iron. Babies who are exclusively breastfed should get a daily oral iron supplement starting at age 4 months and continued until iron-rich solid foods are introduced.

In Western countries, drinking too much cow's milk (usually more than 2 cups per day) is a common cause of iron deficiency in young children. Cow's milk contains little iron and can get in the way of iron absorption. Cow's milk also can also cause irritation and problems in the intestine that lead to blood loss and increased risk for anemia. Babies should not get cow's milk before they are 12 months old.

Iron deficiency most commonly affects babies 9 to 24 months old. All babies should have a screening test for iron deficiency at around age 12 months. Babies born prematurely may need to be tested earlier. Other factors associated with iron-deficiency anemia in infants and small children include:

- Stopping breastfeeding too early or using formula that is not iron-fortified. Ideally, babies should be breastfed for at least their first 4 to 6 months.

- Bottle-feeding too long. Bottle-fed babies who are 7 to 9 months old should be weaned from bottles and given sippy cups. By the age of 12 months, all children should be using a cup instead of a bottle.

- Toddlers' preferences for iron-poor food. Parents should make sure that their children eat iron-rich foods such as beans, meat, fortified cereals, eggs, and green leafy vegetables.

Risk Factors in Premenopausal Women

Up to 10% or more of adolescent and adult women under age 49 years are iron deficient. Anemia among premenopausal women typically occurs from heavy menstrual periods, which are often associated with uterine fibroids or endometriosis.

Pregnancy can also contribute to anemia by:

- Increasing the body's demand for folic acid.

- Increasing the body's demand for iron. Pregnant women need 27 mg of iron per day.

- During delivery, heavy bleeding or multiple births can cause postpartum anemia, which can last 6 to 12 months after giving birth.

Poor Diet

Although most meat-eating Americans probably consume too much iron in their diets, some people may be at risk for diet-related iron deficiencies. In particular, vegans and other strict vegetarians who avoid all animal products are at risk for deficiencies in iron and some B vitamins.

Dried beans and green vegetables contain iron, but the body absorbs iron less easily from plant iron than from meat. Most commercial cereals and grain products are fortified with an easily absorbed form of vitamin B12 and with folic acid (the synthetic form of folate).

Medical Conditions

Anyone with a chronic disease that causes inflammation or bleeding is at risk for anemia. People with alcohol-use disorders are at risk for anemia both from internal bleeding as well as vitamin-deficiency-related anemias. People who donate blood frequently also have an increased risk for iron-deficiency anemia.

- Complications

Most cases of anemia are mild, including those that result from chronic disease. Nevertheless, even mild anemia can reduce oxygen transport in the blood, causing fatigue and diminished physical endurance.

Because a reduction in red blood cells decreases the ability to absorb oxygen from the lungs, serious problems can occur in prolonged and severe anemia that is not treated. Severe anemia can lead to secondary organ dysfunction or damage, including heart arrhythmias and worse outcomes for heart failure.

Complications in Pregnant Women

Pregnant women with significant anemia may have an increased risk for poor pregnancy outcomes, particularly if they are anemic during the first two trimesters. Severe anemia increases the risk for preterm birth and infant low birth weight. Mild anemia is normal during pregnancy and does not pose any increased risk.

Complications in Children and Adolescents

In children, severe anemia can impair growth and motor and mental development. Children may exhibit a shortened attention span and decreased alertness. Children with severe iron-deficiency anemia also have an increased risk for infections.

Complications in Older People

Effects of anemia in the older people include decreased strength and increased risk for falls. Anemia can increase the severity of heart conditions. Studies suggest that anemia may also increase the risk for developing dementia, or worsen existing dementia.

Complications in People with Heart Conditions

Anemia is common in people with coronary artery disease (heart disease), heart failure, history of heart attack, and other heart problems. Anemia is associated with a poorer prognosis and an increased risk for death. It is not clear whether anemia is directly responsible for these worse outcomes or if it is a marker for severe heart disease.

Current guidelines for people with heart conditions recommend treating severe anemia with blood transfusions. Erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs should not be used to treat mild-to-moderate anemia in people with heart failure or heart disease because these medications do not seem to provide much benefit and can increase the risk for blood clots.

Complications in People with Cancer

Anemia is particularly serious in cancer and is associated with a shorter survival time.

Complications in People with Kidney Disease

Anemia is associated with higher mortality rates and possibly heart disease in people with chronic kidney disease.

Complications of Vitamin B12 Deficiencies and Pernicious Anemia

Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause neurologic damage, which can be irreversible if it is left untreated.

- Symptoms

Anemia may occur without symptoms and be detected only during a medical examination that includes a blood test. Symptoms can occur as a result of the cardiovascular system adapting to the lack of oxygen in the blood. Additional symptoms may occur due to the underlying diseases causing the anemia. Symptoms of anemia include:

- Weakness and fatigue are the most common symptoms

- Shortness of breath on exertion

- Rapid heartbeat

- Lightheadedness or dizziness

- Headache

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Irritability and other mood disturbances

- Pale skin (however, healthy-looking skin color does not rule out anemia)

- Coldness in hands or feet

- Mental confusion

Unusual Symptoms

Pica

An odd symptom of iron-deficiency anemia that often occurs in children. Pica is the habit of eating unusual non-nutritive substances, such as ice, clay, cardboard, foods that crunch (such as raw potatoes, carrots, or celery), or raw starch. In many cases, iron deficiency is a cause of pica. This symptom usually stops when iron supplements are given. If present for more than one month and not as a culturally supported practice, pica is considered an eating disorder. Many times, pica occurs with other mental health disorders.

Symptoms of Megaloblastic Anemia

The symptoms of megaloblastic anemia from vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiencies may include not only standard anemic symptoms, but also:

- Changes in surface of the tongue (glossitis), which gives it a shiny, red appearance

- Hair changes (thinning and greying)

- Skin changes (pigmentation)

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Cognitive problems (depression and memory loss)

- Nerve problems (numbness and tingling, vision problems, poor bladder control)

- Diagnosis

Anemia can be the first symptom of a serious illness, so it is very important to determine its cause.

Your health care provider will ask about:

- Your diet

- Any health conditions, surgeries, injuries, medications, or treatments that may be associated with anemia

- Any occurrence of blood in the stool or other signs of internal bleeding

- For women, any history of heavy menstrual bleeding

The provider will check for certain physical signs of anemia. They include swollen lymph nodes, an enlarged spleen, and pale skin or nail color.

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

A complete blood count (CBC) is the standard diagnostic test for anemia. The CBC is a panel of tests that measures red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. For diagnosis of anemia, the CBC provides critical information on the size, volume, and shape of red blood cells (erythrocytes). CBC results include measurements of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and mean corpuscular volume.

Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is the iron-bearing and oxygen-carrying component of red blood cells. The normal value for hemoglobin varies by age and sex. Anemia is generally diagnosed when hemoglobin concentrations fall below 11 g/dL for pregnant women, 12 g/dL for non-pregnant women, and 13 g/dL for men. Values for children depend on the child's age.

Hemoglobin concentration ranges provide information on anemia severity:

- Mild anemia is considered when hemoglobin is between 9.5 to 13.0 g/dL

- Moderate anemia is considered when hemoglobin is between 8.0 to 9.5 g/dL

- Severe anemia is considered for hemoglobin concentrations below 8.0 g/dL

Hematocrit

Hematocrit is the percentage of blood composed of red blood cells. People with a high volume of plasma (the liquid portion of blood) may be anemic even if their blood count is normal because the blood cells have become diluted. Like hemoglobin, a normal hematocrit percentage depends on age and gender. Normal values are between 35% to 45% for women and 39% to 50% for men, with variations due to age. These values may be decreased in anemia.

Other hemoglobin measurements, such as mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) may also be calculated.

Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV)

MCV is a measurement of the average size of red blood cells. The MCV increases when red blood cells are larger than normal (macrocytic) and decreases when red blood cells are smaller than normal (microcytic). Macrocytic cells can be a sign of anemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency, while microcytic cells are a sign of iron-deficiency anemia.

Other Blood Tests

Serum Ferritin

Ferritin is a protein that binds to iron and helps to store iron in the body. Low levels suggest reduced iron stores. Normal values range from 12 to 300 ng/mL for men and 12 to 150 ng/mL for women. Lower than normal levels of ferritin are a sign of iron-deficiency anemia.

Serum Iron

Serum iron measures the amount of iron in the blood. A normal serum iron is 60 to 170 µg/dL. Lower levels may indicate iron-deficiency anemia or anemia of chronic disease.

Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC)

TIBC measures the level of transferrin saturation in the blood. Transferrin is a protein that carries iron in the blood. TIBC calculates how much or how little of the transferrin in the body is carrying iron. A higher than normal TIBC is a sign of iron-deficiency anemia. A lower than normal level may indicate anemia of chronic disease, sickle cell, pernicious anemia, or hemolytic anemia.

Reticulocyte Count

Reticulocytes are young red blood cells, and their count reflects the rate of red blood cell production. Normal values vary between 0.5% to 1.5%. A low count, when bleeding isn't the cause, suggests production problems in the bone marrow. An abnormally high count indicates that red blood cells are being destroyed in high numbers and indicates hemolytic anemia.

Vitamin Deficiencies

The provider may order tests for vitamin B12 and folate levels. Tests for methylmalonic acid and homocysteine levels are more specific for deficiencies in these vitamins.

Other Diagnostic Tests

If internal bleeding is suspected as the cause of anemia, the gastrointestinal (digestive) tract is usually the first possible source. Telltale signs are bloody stools, which may be black and tarry or red-streaked. Often, however, bleeding may be present but not visible. If so, stool tests for this hidden (occult) fecal blood are necessary.

Additional tests may be ordered to check for gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy uses a thin fiber-optic tube to view the esophagus, stomach, and areas in the small intestine. Colonoscopy is used to view the lower intestine and rectum and may also be recommended to rule out colorectal cancer.

Women with heavy menstrual bleeding may be referred to a gynecologist for pelvic ultrasound, endometrial biopsy, and other gynecological diagnostic exams.

If the person's diet suggests low iron intake and other causes cannot easily be established, the provider may recommend trying iron supplements for a few months. If red blood cell count and iron levels fail to improve, further evaluation is needed.

- Dietary Factors

Iron found in foods is either in the form of heme iron (attached to hemoglobin molecule) or non-heme iron:

- Heme Iron. Foods containing heme iron are the best sources for increasing or maintaining healthy iron levels. Such foods include (in decreasing order of iron-richness) clams, oysters, organ meats, beef, pork, poultry, and fish.

- Non-Heme Iron. Non-heme iron is less well-absorbed. About 60% of the iron in meat is non-heme (although meat itself helps absorb non-heme iron). Eggs, dairy products, and iron-containing vegetables have only the non-heme form. Plant-based sources of iron include dried beans and peas, iron-fortified cereals, bread, and pasta products, dark green leafy vegetables (such as chard, spinach, mustard greens, and kale), dried fruits, nuts, and seeds.

The absorption of non-heme iron often depends on the food balances in meals. The following foods and cooking methods can enhance absorption of iron:

- Meat and fish not only contain heme iron, which is the best form for maintaining stores, but they also help absorb non-heme iron.

- Increasing intake of vitamin-C rich foods, such as orange juice, may enhance absorption of non-heme iron, although it is not clear if it improves iron stores in iron-deficient people. Vitamin-C rich foods include broccoli, cabbage, citrus fruits, melon, tomatoes, and strawberries.

- Riboflavin (vitamin B2) may help enhance the response of hemoglobin to iron. Food sources include dairy products, liver, and dried fortified cereals.

- Cooking methods can enhance iron stores. Cooking in cast iron pans and skillets can help increase the iron content of food.

- Vitamins B12 and folate are important for prevention of megaloblastic anemia and for good health in general. Dietary sources of vitamin B12 are animal products, such as meats, dairy products, eggs, and fish (clams and oily fish are very high in B12). Vitamin B12 is not found in plant foods. As is the case with other B vitamins, vitamin B12 is added to fortified commercial dried cereals.

- Folate (vitamin B9) is found in avocado, bananas, orange juice, cold cereal, asparagus, fruits, green, leafy vegetables, dried beans and peas, and yeast. The synthetic form, folic acid, is added to commercial grain products. Vitamins are usually made from folic acid, which is about twice as potent as folate.

Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA)

Iron

The Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of iron for people who are not iron deficient varies by age group and other risk factors. (Iron supplements are rarely recommended in people without evidence of iron deficiency or anemia.) The RDA for iron intake is:

- Infants 0 to 6 months: 0.27 mg

- Infants 7 to 12 months: 11 mg

- Children 1 to 3 years old: 7 mg

- Children 4 to 8 years old: 10 mg

- Children 9 to 13 years old: 8 mg

- Males 14 to 18 years old: 11 mg

- Females 14 to 18 years old: 15 mg

- Males 19 to 50 years old: 8 mg

- Females 19 to 50 years old: 8 mg

- Pregnancy: 27 mg

- Breastfeeding females 14 to 18 years old: 10 mg

- Breastfeeding females 19 to 50 years old: 9 mg

- Older adults (over age 50 years): 8 mg

Vitamin B12

The RDA for vitamin B12 for adults is 2.4 µg a day. The RDA for vitamin B12 is increased in women who are pregnant (2.6 µg) or breastfeeding (2.8 µg).

Folate

The RDA of folic acid or folate for teenagers and adults is 400 µg. The RDA for folate is increased in women who are pregnant (600 µg) or breastfeeding (500 µg).

Preventing Anemia in Infants and Small Children

The main source of iron for an infant from birth to 1 year of age is from breast milk, iron-fortified infant formula, or cereal.

Breastfeeding and Iron-Supplemented Formulas

Mothers should try to breastfeed their babies for their first year. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends exclusively breastfeeding for a minimum of 4 months, but preferably 6 months, then gradually adding solid foods while continuing to breastfeed until at least the baby's first birthday.

Because human breast milk contains very little iron, the AAP recommends that full-term healthy infants receive a daily oral iron supplement of 1 mg/kg beginning at age 4 months and continuing until iron-rich complementary foods, such as iron-fortified cereals, are introduced. Preterm infants who are breastfed should receive an iron supplement of 2 mg/kg by the time they are 1 month old.

Infants who are not breastfed should receive iron-fortified formulas (4 to 12 mg/L for their first year of life). Parents should discuss the best formula with their child's provider. The AAP does not recommend cow's milk for children under 1 year old. The baby will begin drinking less formula or breast milk once solid foods become a source of nutrition. At 8 to 12 months of age, a baby will be ready to try strained or finely chopped meats. When cereals are begun, they should be iron fortified.

Recommendations for Toddlers

Toddlers who did not have iron supplements during infancy should be checked for iron deficiency. After the first year, children should be given a varied diet that is rich in sources of iron, B vitamins, and vitamin C. Good sources of iron include iron-fortified grains and cereals, egg yolks, red meat, potatoes (cooked with skin on), tomatoes, molasses, and raisins.

Cow's milk does not contain enough iron, interferes with iron absorption, and can decrease children's appetite for iron-rich foods. Toddlers older than 1 year should not drink more than 2 cups of milk a day. Fruits that are rich in vitamin C can help boost iron absorption. Most children will receive adequate iron from a well-balanced diet, but some toddlers may benefit from liquid supplements or chewable multivitamins.

- Treatment

Oral iron supplements are the best way to restore iron levels for people who are iron deficient, but they should be used only when dietary measures have failed. Iron supplements cannot correct anemias that are not due to iron deficiency.

Iron replacement therapy can cause gastrointestinal problems, sometimes severe ones. Excess iron may also contribute to heart disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. Experts generally advise against iron supplements in anyone with a healthy diet and no indications of iron deficiency anemia.

Treatment of Anemia of Chronic Disease

In general, the best treatment for anemia of chronic diseases is treating the disease itself. In some cases, iron deficiency accompanies the condition and requires iron replacement. Erythropoietin, most often administered with intravenous iron, is used for some people.

Oral Iron Supplements

Supplement Forms

There are two forms of supplemental iron: ferrous and ferric. Ferrous iron is better absorbed and is the preferred form of iron tablets. Ferrous iron is available in 3 forms:

- Ferrous fumarate

- Ferrous sulfate

- Ferrous gluconate

The label of an iron supplement contains information both on the tablet size (which is typically 325 mg) and the amount of elemental iron contained in the tablet (the amount of iron that is available for absorption by the body.) When selecting an iron supplement, it is important to look at the amount of elemental iron.

A 325 mg iron supplement contains the following amounts of elemental iron depending on the type of iron:

- Ferrous fumarate. 108 mg of elemental iron

- Ferrous sulfate. 65 mg of elemental iron

- Ferrous gluconate. 35 mg of elemental iron

Dosage

Depending on the severity of your anemia, as well as your age and weight, your health care provider will recommend a dosage of 60 to 200 mg of elemental iron per day. This means taking 1 iron pill 2 to 3 times during the day. Make sure your provider explains to you how many pills you should take in a day and when you should take them. Never take a double dose of iron.

Side Effects and Safety

Common side effects of iron supplements include:

- Constipation and diarrhea are very common. They are rarely severe, although iron tablets can aggravate existing gastrointestinal problems such as ulcers and ulcerative colitis.

- Nausea and vomiting may occur with high doses, but taking smaller amounts of medicine can control the problem. Switching to ferrous gluconate may help some people with severe gastrointestinal problems.

- Black stools are normal when taking iron tablets. In fact, if they do not turn black, the tablets may not be working effectively. This problem tends to be more common with coated or long-acting iron tablets.

- If the stools are tarry looking as well as black, if they have red streaks, or if cramps, sharp pains, or soreness in the stomach occur, gastrointestinal bleeding may be causing the iron deficiency. You should contact your health care provider right away.

- Acute iron poisoning is rare in adults but can be fatal in children who take adult-strength tablets. Keep iron supplements out of the reach of children. If your child swallows an iron pill, immediately contact a poison control center.

Other Tips for Safety and Effectiveness

Other tips for taking iron are as follows:

- For best absorption, iron should be taken between meals. Iron may cause stomach and intestinal disturbances, however. Low doses of ferrous sulfate can be taken with food and are still absorbed but with fewer side effects.

- Drink a full 8 ounces of fluid with an iron pill. Taking orange juice with an iron pill can help increase iron absorption. (Some providers also recommend taking a vitamin C supplement with the iron pill.)

- If constipation becomes a problem, take a stool softener such as docusate sodium (Colace).

- Certain medications, including antacids, can reduce iron absorption. Iron tablets may also reduce the effectiveness of other drugs, including the antibiotics tetracycline, penicillin, and ciprofloxacin and the Parkinson disease drugs methyldopa, levodopa, and carbidopa. At least 2 hours should elapse between doses of these drugs and iron supplements.

- Avoid taking milk, caffeine, antacids, or calcium supplements at the same time as an iron pill because they can interfere with iron absorption.

- Tablets should be kept in a cool place. (Bathroom medicine cabinets may be too warm and humid, which may cause the pills to disintegrate.)

An increase in hemoglobin of 1 g/dL after one month of iron therapy confirms the diagnosis and indicates that the treatment is working. However, iron therapy should be continued for 3 months after the anemia is corrected to replenish the body's iron stores in the bone marrow.

Intravenous Iron

In some cases, supplemental iron is administered intravenously. Intravenous iron is used to treat iron-deficiency anemia. It may be recommended for people who:

- Are unable to absorb oral iron or have anemia that has continued to worsen after taking oral iron

- Have very severe iron deficiency or blood loss

- Have serious gastrointestinal disorders, such as severe inflammatory bowel disease, or have had stomach or intestine surgery and cannot take iron therapy by mouth

- Are receiving supplemental erythropoietin therapy

Intravenous iron may be given in the form of iron dextran (Dexferrum, INFeD), iron sucrose (Venofer), ferric gluconate (Ferrlecit), ferumoxytol (Feraheme), or ferric carboxymaltose (Injectafer). Your provider may refer you to a hematologist (a doctor who specializes in blood disorders) to oversee this treatment.

Some intravenous iron can cause an allergic reaction. It might be important to administer a test dose before you receive your first infusion. The risk for allergic reactions is higher with iron dextran than with other forms of intravenous iron. Intravenous iron should never be given at the same time as oral iron supplements.

Blood Transfusions

Transfusions are used to replace blood loss due to injuries and during certain surgeries. They are also commonly used to treat people who have thalassemia, sickle cell disease, myelodysplastic syndromes, or other severe types of anemia. In certain cases, blood transfusions may be used to treat severe anemia associated with heart disease.

Some people require frequent blood transfusions, which can cause a side effect of iron overload. If left untreated, iron overload can lead to liver and heart damage.

Iron chelation therapy is used to remove the excess iron caused by blood transfusions. It uses a drug that binds to the iron in the blood. The bound form of excess iron is then removed from the body by the kidneys. Deferasirox (Jadenu) is an example of medicine for iron overload due to blood transfusions.

Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Drugs

Erythropoietin is the hormone that acts in the bone marrow to increase the production of red blood cells. It has been genetically engineered as recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) and is available as epoetin alfa (Epogen, Procrit, Retacrit). Novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP), also called darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp), lasts longer in the blood than epoetin alfa and requires fewer injections. These medications are also called "erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs."

Levels of erythropoietin are reduced in anemia of chronic disease. Injections of synthetic erythropoietin can help increase the number of red blood cells in order to avoid receiving blood transfusions.

Synthetic erythropoietin can cause serious side effects, including blood clots, and is approved only for treating select people with anemia related to certain conditions such as anemia caused by chronic kidney disease, cancer chemotherapy, and HIV/AIDS treatment with zidovudine.

Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Drugs and Cancer

Erythropoietin may be used to treat anemia caused by chemotherapy. Erythropoietin treatment does not help prolong survival, but can improve quality of life during cancer treatment by improving anemia.

However, these drugs may shorten lifespan and may cause some tumors to grow faster. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Society of Hematology recommend starting erythropoietin for chemotherapy-associated anemia only if the hemoglobin level is less than 10 g/dL. These drugs should not be used when the goal of the chemotherapy is to cure the cancer.

Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Drugs and Chronic Kidney Disease

For people with chronic kidney disease or kidney failure, the FDA currently recommends that erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs be considered when hemoglobin levels are lower than 10 g/dL.

Warning Symptoms

Contact your provider if you have any of the following symptoms while being treated with an erythropoiesis-stimulating drug:

- Pain or swelling in the legs

- Worsening in shortness of breath

- Increases in blood pressure (be sure to regularly monitor your blood pressure)

- Dizziness or loss of consciousness

- Extreme fatigue

- Blood clots in hemodialysis vascular access ports

Guidelines for Treating Anemia in People with Heart Problems

The American College of Physicians (ACP) has clinical practice guidelines for treating anemia in people with heart failure, coronary artery disease, or heart attack. According to the ACP, current evidence suggests as best practice for people with heart conditions:

- Blood transfusions may be effective for severe anemia, but are not helpful for milder anemia.

- Erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs should not be used to treat mild-to-moderate anemia; these drugs can increase the risk for blood clots and other problems.

- There is insufficient evidence to determine if intravenous iron is beneficial for people with heart conditions who have iron-deficiency anemia.

Vitamin Replacement for Megaloblastic Anemia

If folate deficiency is responsible, treatment usually involves taking a daily oral folic acid supplement until laboratory tests show levels have returned to normal, as well as increasing intake of foods rich in folate. When vitamin B12 deficiency is responsible, vitamin B12 supplementation may be administered in tablets, injections of cyanocobalamin (Cobal 1000) or hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit), or as a nasal spray. Often both folate and vitamin B12 are needed to treat megaloblastic anemia.

- Resources

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute -- www.nhlbi.nih.gov

- American Society of Hematology -- www.hematology.org

- National Institutes of Health: Office of Dietary Supplements -- ods.od.nih.gov

References

Baker RD, Greer FR; Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0-3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040-1050. PMID: 20923825 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20923825.

Brittenham GM. Disorders of iron homeostasis: iron deficiency and overload. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, et al, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 36.

De Franceschi L, Iolascon A, Taher A, Cappellini MD. Clinical management of iron deficiency anemia in adults: systemic review on advances in diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;42:16-23. PMID: 28528999 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28528999.

Green R, Datta Mitra A. Megaloblastic anemias: nutritional and other causes. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101(2):297-317. PMID: 28189172 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28189172.

Hesdorffer CS, Longo DL. Drug-induced megaloblastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(17):1649-1658. PMID: 26488695 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26488695.

Lopez A, Cacoub P, Macdougall IC, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):907-916. PMID: 26314490 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26314490.

Mason JB, Booth SL. Vitamins, trace minerals, and other micronutrients. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 205.

Means RT. Approach to the anemias. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 149.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer- and chemotherapy-induced anemia. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Version 1.2018. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/anemia.pdf.

Nayak L, Gardner LB, Little JA. Anemia of chronic diseases. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, et al, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 37.

Padhi S, Glen J, Pordes BA, Thomas ME; Guideline Development Group. Management of anaemia in chronic kidney disease: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h2258. PMID: 26044132 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26044132.

Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Fitterman N, Starkey M, Shekelle P; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of anemia in patients with heart disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(11):770-779. PMID: 24297193 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24297193.

Rothman JA. Iron-deficiency anemia. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 482.

Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for iron deficiency anemia in young children: USPSTF Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):746-752. PMID: 26347426 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26347426.

Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for iron deficiency anemia and iron supplementation in pregnant women to improve maternal health and birth outcomes: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):529-536. PMID: 26344176 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26344176.

Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):2041-2042. PMID: 23697526 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23697526.

Stabler SP. Megaloblastic anemias. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 155.